The year 1777 was most critical for the British. The issue, very plainly, was whether they could score such success in putting down the American revolt that the French would not dare enter the war openly to aid the American rebels. Yet it was in this critical year that British plans were most confused and British operations most disjointed. The British campaign Of 1777 provides one of the most striking object lessons in military history of the dangers of divided command.

The year 1777 was most critical for the British. The issue, very plainly, was whether they could score such success in putting down the American revolt that the French would not dare enter the war openly to aid the American rebels. Yet it was in this critical year that British plans were most confused and British operations most disjointed. The British campaign Of 1777 provides one of the most striking object lessons in military history of the dangers of divided command.

The Campaign Of 1777

With secure bases at New York and Newport, Howe had a chance to get the early start that had been denied him the previous year. His first plan, advanced on November 30, 1776, was probably the most comprehensive put forward by any British commander during the war. He proposed to maintain a small force of about 8,000 to contain Washington in New Jersey and 7,000 to garrison New York, while sending one column of 10,000 from Newport into New England and another column of 10,000 from New York up the Hudson to form a junction with a British force moving down from Canada, on the assumption that these moves would be successful by autumn, he would next capture Philadelphia, the rebel capital, and then make the southern provinces the "objects of the winter." For this plan, Howe requested 35,000 men, 15,000 more effective troops than he had left at the. end of the 1776 campaign. Sir George Germain, the American Secretary, could promise him only 8,000. Even before receiving this news, but evidently influenced by Trenton and Princeton, Howe changed his plan and proposed to devote his main effort in 1777 to taking Philadelphia.

On March 3, 1777, Germain informed Howe that the Philadelphia plan was approved, but that there might be only 5,500 reinforcements. At the same time Germain and the king urged a "warm diversion" against New England.

Meanwhile, Sir John Burgoyne, who had succeeded in obtaining the separate military command in Canada, submitted his plan calling for an advance southward to "a junction with Howe." Germain and the king also approved this plan on March 29, though aware of Howe's intention to go to Philadelphia. They seem to have expected either that Howe would be able to form his Junction by the "warm diversion," or else that he would take Philadelphia quickly and then turn north to aid Burgoyne.

In any case, Germain approved two separate and un-co-ordinated plans, and Howe and Burgoyne went their separate ways, doing nothing to remedy the situation. Howe's Philadelphia plan did provide for leaving enough force in New York for what its commander, General Clinton, called "a damn'd starved offensive," but Clinton's orders were vague. Quite possibly Burgoyne knew before he left England for Canada that Howe was going to Philadelphia, but ambitious "Gentleman Johnny" was determined to make a reputation in the American war, and evidently believed he could succeed alone. Even when he learned on August 3, 1777 that he could not expect Howe's co-operation, he persisted in his design.

As Howe thought Pennsylvania was filled with royalists, Burgoyne cherished the illusion that legions of Tories in New York and western New England were simply awaiting the appearance of the king's troops to rally to the colors.

Again in 1777 the late arrival of Howe's reinforcements and stores ships gave Washington time that he sorely needed. Men to form the new Continental Army came in slowly and not until June did the Americans have a force of 8,000.

On the northern line the defenses were even more thinly manned. Supplies for troops in the field were also short, but the arrival of the first three ships bearing secret aid from France vastly improved the situation. They were evidence of the covert support of the French Government; a mission sent by Congress to France was meanwhile working diligently to enlist open aid and to embroil France in a war with England. The French Foreign Minister, the Comte de Vergennes, had already decided to take that risk when and if the American rebels demonstrated their serious purpose and ability to fulfill it by some signal victory in the field.

With the first foreign material aid in 1777, the influx of foreign officers into the American Army began. These officers were no unmixed blessing. Most were adventurers in search of fortune or of reputation with little facility for adjusting themselves to American conditions. Few were willing to accept any but the highest ranks. Nevertheless, they brought with them professional military knowledge and competence that the Continental Army sorely needed. When the misfits were culled out, this knowledge and competence were used to considerable advantage. Louis DuPortail, a Frenchman, and Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a Pole, did much to advance the art of engineering in the Continental Army; Casimir Pulaski, another Pole, organized its first genuine cavalry contingent; Johann de Kalb and Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, both Germans, and the Marquis de Lafayette, an influential French nobleman who financed his own way, were all to make valuable contributions as trainers and leaders. On the Continental Army of 1777, however, these foreign volunteers had little effect and it remained much as it had been before, a relatively untrained body of inexperienced enlistees.

When Howe finally began to stir in June 1777, Washington posted his army at Middlebrook, New Jersey, in a position either to bar Howe's overland route to Philadelphia or to move rapidly up the Hudson to oppose an advance northward. Washington confidently expected Howe to move northward to form a junction with Burgoyne, but decided he must stay in front of the main British Army wherever it went.

Following the principle of economy of force, he disposed a small part of his army under General Putnam in fortifications guarding the approaches up the Hudson, and at a critical moment detached a small force to aid Schuyler against Burgoyne. The bulk of his army he kept in front of Howe in an effort to defend Philadelphia. Forts were built along the Delaware River and other steps taken to block the approach to the Continental capital by sea.

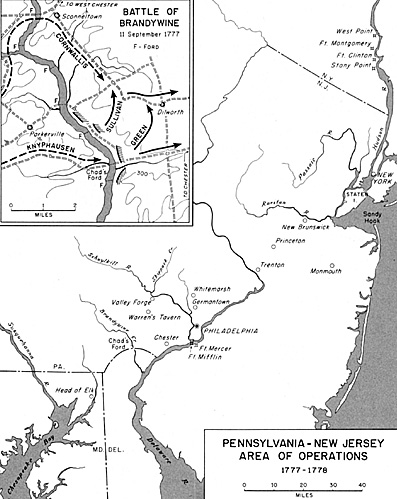

In the effort to defend Philadelphia Washington again failed, but hardly so ignominiously as he had the year before in New York. After maneuvering in New Jersey for upward of two months, Howe in August put most of his army on board ship and sailed down the coast and up the Chesapeake Bay to Head of Elk (a small town at the head of the Elk River) in Maryland, putting himself even further away from Burgoyne.

Though surprised by Howe's movement, Washington rapidly shifted his own force south and took up a position at Chad's Ford on Brandywine Creek, blocking the approach to Philadelphia. There on September 11, 1777, Howe executed a flanking movement not dissimilar to that employed on Long Island and again defeated Washington. The American commander had disposed his army in two main parts, one directly opposite Chad's Ford under his personal command and the other under General Sullivan guarding the right flank upstream.

While Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen's Hessian troops demonstrated opposite the ford, a larger force under Lord Cornwallis marched upstream, crossed the Brandywine, and moved to take Sullivan from the rear. Washington lacked good cavalry reconnaissance, and did not get positive information on Cornwallis' movement until the eleventh hour. Sullivan was in the process of changing front when the British struck and his men retreated in confusion. Washington was able to salvage the situation by dispatching General Greene with two brigades to fight a valiant rear-guard action, but the move weakened his front opposite Kynphausen and his forces also had to fall back. Nevertheless, the trap was averted and the Continental Army retired in good order to Chester.

Howe followed with a series of maneuvers comparable to those he had executed in New York, and was able to enter Philadelphia with a minimum of fighting on September 26, A combined attack of British Army and Navy forces shortly afterward reduced the forts on the Delaware and opened the river as a British supply line.

On entering Philadelphia, Howe dispersed his forces, stationing 9,000 men at Germantown north of the city, 3,000 in New Jersey, and the rest in Philadelphia.

Battle of Germantown

Battle of Germantown

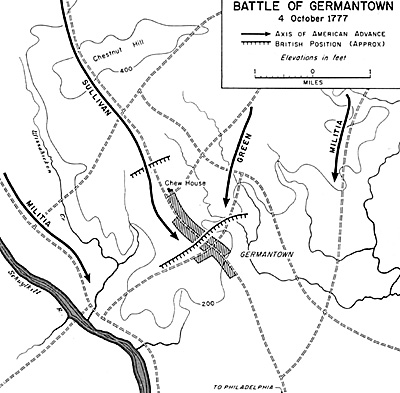

As Howe had repeated his performance in New York, Washington sought to repeat Trenton by a surprise attack on Germantown. The plan was much like that-used at Trenton but involved far more complicated movements by much larger bodies of troops. Four columns-two of Continentals under Sullivan and Greene and two of militia-moving at night over different roads were to converge on Germantown simultaneously at dawn on October 4.

The plan violated the principle of simplicity, for such a maneuver was difficult even for well-trained professionals to execute. The two columns of Continentals arrived at different times and fired on each other in an early morning fog. The two militia columns never arrived at all. British fire from a stone house, the Chew Mansion, held up the advance while American generals argued whether they could leave a fortress in their rear. The British, though surprised, had better discipline and cohesion and were able to re-form and send fresh troops into the fray. The Americans retreated about 9:00 a.m., leaving Howe's troops in command of the field.

After Germantown Howe once again concentrated his army and moved to confront Washington at Whitemarsh, but finally withdrew to winter quarters in Philadelphia without giving battle. Washington chose the site for his own winter quarters at a place called Valley Forge, twenty miles northwest of the city. Howe had gained his objective but it proved of no lasting value to him. Congress fled west to York, Pennsylvania. No swarms of loyalists rallied to the British standards. And Howe had left Burgoyne to lose a whole British army in the north.

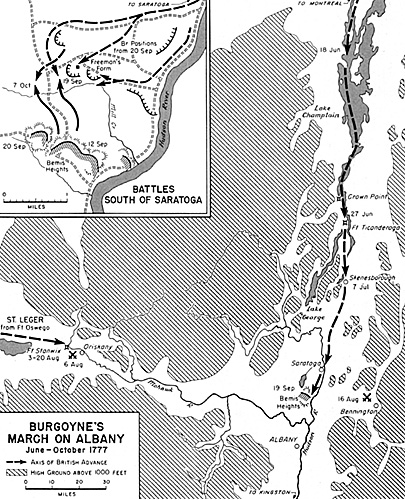

Burgoyne set out from Canada in June, his object to reach Albany by fall. His force was divided into two parts. The first and largest part--7,200 British and Hessian Regulars and 650 Tories, Canadians, and Indians, under his personal command -- was to take the route down Lake Champlain to Ticonderoga and thence via Lake George to the Hudson. The second-700 Regulars and 1,000 Tories and Indian braves under Col. Barry St. Leger-was to move via Lake Ontario to Oswego and thence down the Mohawk Valley to join Burgoyne before Albany. In his preparations, Burgoyne evidently forgot the lesson the British had learned in the French and Indian War, that in the wilderness troops had to be prepared to travel light and fight like Indians.

He carried 138 pieces of artillery and a heavy load of officers' personal baggage. Numerous ladies of high and low estate accompanied the expedition. When he started down the lakes, Burgoyne did not have enough horses and wagons to transport his artillery and baggage once he had to leave the water and move overland.

At first Burgoyne's American opposition was very weak--only about 2,500

Continentals at Ticonderoga and about 450 at old Fort Stanwix, the sole American

bulwark in the Mohawk Valley. Dissension among the Americans was rife, the

New Englanders refusing to support Schuyler, the aristocratic New Yorker who commanded the Northern Army, and openly intriguing to replace him with their own favorite, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. Ticonderoga fell to Burgoyne on June 27 all too easily. American forces dispersed and Burgoyne pursued the remnants down to Skenesborough. Once that far along, he decided to continue overland to the Hudson instead of returning to Ticonderoga to float his force down Lake George, though much of his impedimenta still had to be carried by boat down the lake.

At first Burgoyne's American opposition was very weak--only about 2,500

Continentals at Ticonderoga and about 450 at old Fort Stanwix, the sole American

bulwark in the Mohawk Valley. Dissension among the Americans was rife, the

New Englanders refusing to support Schuyler, the aristocratic New Yorker who commanded the Northern Army, and openly intriguing to replace him with their own favorite, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. Ticonderoga fell to Burgoyne on June 27 all too easily. American forces dispersed and Burgoyne pursued the remnants down to Skenesborough. Once that far along, he decided to continue overland to the Hudson instead of returning to Ticonderoga to float his force down Lake George, though much of his impedimenta still had to be carried by boat down the lake.

The overland line of advance was already a nightmare, running along wilderness trails, through marshes, and across wide ravines and creeks that had been swollen by abnormally heavy rains. Schuyler adopted the tactic of making it even worse by destroying bridges, cutting trees in Burgoyne's path, and digging trenches to let the waters of swamps onto drier ground. The British were able to move at a rate of little more than a mile a day and took until July 29 to reach Fort Edward on the Hudson. By that time Burgoyne was desperately short of horses, wagons, and oxen. Yet Schuyler, with a unstable force of 4,500 men discouraged by continual retreats, was in no position to give battle.

Washington did what he could to strengthen the Northern Army at this juncture. He first dispatched Mal. Gen. Benedict Arnold, his most aggressive field commander, and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, a Massachusetts man noted for his influence with the New England militia. On August 16 he detached Col. Daniel Morgan with 500 riflemen from the main army in Pennsylvania and ordered them along with 750 men from Putnam's force in the New York highlands to join Schuyler. The riflemen were calculated to furnish an antidote for Burgoyne's Indians who, despite his efforts to restrain them, were terrorizing the countryside.

It was the rising militia, rather than Washington, who were to provide the Northern Army with its main reinforcements. Nothing worked more to produce this result than Burgoyne's employment of Indians. The murder and scalping of a beautiful white woman, Jane McCrea, dramatized the Indian threat as nothing else probably could have done. New England militiamen now began to rally to the cause, though they still refused to co-operate with Schuyler. New Hampshire commissioned John Stark, a disgruntled ex-colonel in the Continental Army and a veteran of Bunker Hill and Trenton, as a brigadier general in the state service (a rank denied him by Congress), and Stark quickly recruited 2,000 men.

Refusing Schuyler's request that he join the main army, Stark took up a position at Bennington in southern Vermont to guard the New England frontier. On August 11 Burgoyne detached a force of 650 men under Hessian Col. Friedrich Baum to forage for cattle, horses, and transport in the very area Stark was occupying. At Bennington on August 16 Stark nearly annihilated Baum's force, and reinforcements sent by Burgoyne arrived on the field just in time to be soundly thrashed in turn. Burgoyne not only failed to secure his much-needed supplies and transport but also lost about a tenth of his command.

Meanwhile, St. Leger with his Tories and Indians had appeared before Fort Stanwix on August 2. The garrison, fearing massacre by the Indians, determined to hold out to the bitter end. On August 4, the Tryon County militia under Brig. Gen. Nicholas Herkimer set out to relieve the fort but were ambushed by the Indians in a wooded ravine near Oriskany. The militia, under the direction of a mortally wounded Herkimer, scattered in the woods and fought a bloody afternoon's battle in a summer thunderstorm. Both sides suffered heavy losses, and though the militia were unable to relieve Stanwix the losses discouraged St. Leger's Indians, who were already restless in the static siege operation at Stanwix.

Despite his own weak position, when Schuyler learned of the plight of the Stanwix garrison, he courageously detached Benedict Arnold with 950 Continentals to march to its relief. Arnold devised a ruse that took full advantage of the dissatisfaction and natural superstition of the Indians. Employing a half-wit Dutchman, his clothes shot full of holes, and a friendly Oneida Indian as his messengers, Arnold spread the rumor that the Continentals were approaching as numerous as the leaves on the trees." The Indians, who had special respect for any madman, departed in haste, scalping not a few of their Tory allies as they went, and St. Leger was forced to abandon the siege.

Bennington and Stanwix were serious blows to Burgoyne. By early September he knew he could expect help from neither Howe nor St. Leger. Disillusioned about the Tories, he wrote Germain: "The great bulk of the country is undoubtedly with Congress in principle and zeal; and their measures are executed with a secrecy and dispatch that are not to be equalled. Wherever the King's forces point, militia in the amount of three or four thousand assemble in twenty-four hours; they bring with them their subsistence, etc., and the alarm over, they return to their farms. . . ."

Nevertheless, gambler that he was Burgoyne crossed the Hudson to the west side during September 13 and 14 signaling his intention to get to Albany or lose his army. While his supply problem daily became worse, his Indians, with a natural instinct for sensing approaching disaster, drifted off into the forests, leaving him with little means of gaining intelligence of the American dispositions.

The American forces were meanwhile gathering strength. Congress finally deferred to New England sentiment on August ig and replaced Schuyler with Gates. Gates was more the beneficiary than the cause of the improved situation, but his appointment helped morale and encouraged the New England militia. Washington's emissary, General Lincoln, also did his part. Gates understood Burgoyne's plight perfectly and adapted his tactics to take full advantage of it. He advanced his forces four miles northward and took up a position, surveyed and prepared by the Polish engineer, Kosciusko, on Bemis Heights, a few miles below Saratoga.

Against this position Burgoyne launched his attack on September 19 and was repulsed with heavy losses. In the battle, usually known as Freeman's Farm, Arnold persuaded Gates to let him go forward to counter the British attack, and Colonel Morgan's riflemen, in a wooded terrain well suited to the use of their specialized weapon, took a heavy toll of British officers and men.

After Freeman's Farm, the lines remained stable for three weeks. Burgoyne had heard that Clinton, with the force Howe had left in New York, had started north to relieve him. Clinton, in fact, stormed Forts Clinton and Montgomery on the Hudson on October 6, but, exercising that innate caution characteristic of all his actions, he refused to gamble for high stakes. He simply sent an advance guard on to Kingston and he himself returned to New York.

Burgoyne was left to his fate. Gates strengthened his entrenchments and calmly awaited the attack he was sure Burgoyne would have to make. Militia reinforcements increased his forces to around 10,000 by October 7. Meanwhile Burgoyne's position grew more desperate. Food was running out; the meadows were grazed bare by the animals; and every day more men slipped into the forest, deserting the lost cause. With little intelligence of American strength or dispositions, on October 7 he sent out a "reconnaissance in force" to feel out the American positions.

On learning that the British were approaching, Gates sent out a contingent including Morgan's riflemen to meet them, and a second battle developed, usually known as Bemis Heights. The British suffered severe losses, five times those of the Americans, and were driven back to their fortified positions. Arnold, who had been at odds with Gates and was confined to his tent, broke out, rushed into the fray, and again distinguished himself before he was wounded in leading an attack on Breymann's Redoubt.

Two days after the battle, Burgoyne withdrew to a position in the vicinity of Saratoga. Militia soon worked around to his rear and cut his supply lines. His position hopeless, Burgoyne finally capitulated on October 17 at Saratoga. The total prisoner count was nearly 6,000 and great quantities of military stores fell into American hands. The victory at Saratoga brought the Americans out well ahead in the campaign of 1777 despite the loss of Philadelphia. What had been at stake soon became obvious. In February 1778 France negotiated a treaty of alliance with the American states, tantamount to a declaration of war against England.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 3

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com