If the British ever had a single strategic objective in the war, it was the Hudson River-Lake Champlain line. By taking and holding this line the British believed they could separate New England, considered to be the principal center of the rebellion, from the more malleable colonies to the southward. Howe proposed to make this the main objective of his campaign in 1776 by landing at New York, securing a base of operations there, and then pushing north.

He wanted to concentrate the entire British force in America in New York, but the British Government diverted part of it to Canada in early 1776 to repel the American invasion, laying the groundwork for the divided command that was so to plague British operations afterward.

After the evacuation of Boston, Howe stayed at Halifax from March until June, awaiting the arrival of supplies and reinforcements. While he tarried, the British Government ordered another diversion in the south, aimed at encouraging the numerous loyalists who, according to the royal governors watching from their havens on board British warships, were waiting only for the appearance of a British force to rise and overthrow rebel rule.

Unfortunately for the British, the naval squadron sent from England under Admiral Sir Peter Parker was delayed and did not arrive off the American coast until late in May. By this time all hopes of effective co-operation with the Tories had been dashed. Loyalist contingents had been completely defeated and dispersed in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Parker, undeterred by these developments, determined to attack Charleston, the largest city in the south. There South Carolina militia and newly raised Continentals had prepared and manned defenses under the guidance of Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, whom Washington had dispatched south to assist them. The South Carolinians, contrary to Lee's advice, centered their defenses in Fort Moultrie, a palmetto log fort constructed on Sullivan's Island, commanding the approach to the harbor. It was an unwise decision, somewhat comparable to that at Bunker Hill, but fortunately for the defenders the British had to mount an uncoordinated attack in haste.

Clinton's troops were landed on nearby Long Island, but on the day the Navy attacked, June 28, the water proved too deep for them to wade across to Sullivan's Island as expected. The British Army consequently sat idly by while the gunners in Fort Moultrie devastated the British warships. Sir Peter Parker suffered the ultimate indignity when his pants were set afire.

The battered British Fleet hastily embarked the British soldiers and sailed northward to join Howe, for it was already behind schedule. For three years following the fiasco at Charleston the British were to leave the south unmolested and the Tories there, who were undoubtedly numerous, without succor.

Howe was meanwhile beset by other delays in the arrival of transports from England, and his attack did not get under way until late August-leaving insufficient time before the advent of winter to carry through the planned advance along the Hudson-Lake Champlain line. He therefore started his invasion of New York with only the limited objective of gaining a foothold for the campaign the following year.

The British commander had, when his force was all assembled, an army of about 32,000 men; it was supported by a powerful fleet under the command of his brother, Admiral Richard Howe. To oppose him Washington had brought most of his army down from Boston, and Congress exerted its utmost efforts to reinforce him by raising Continental regiments in the surrounding states and issuing a general call for the militia. Washington was able to muster a paper strength of roughly 28,500 men, but only about 19,000 were present and fit for duty. As Christopher Ward remarks, "The larger part of them were raw recruits, undisciplined and inexperienced in warfare, and militia, never to be assuredly relied upon."

Washington and Congress made the same decision the South Carolinians had made at Charleston--to defend their territory in the most forward positions-- and this time they paid the price for their mistake. The geography of the area gave the side possessing naval supremacy an almost insuperable advantage. The city of New York stood on Manhattan Island, surrounded by the Hudson, Harlem, and East Rivers. There was only one connecting link with the mainland, Kingsbridge across the Harlem River at the northern tip of Manhattan.

Across the East River on Long Island, Brooklyn Heights stood in a position dominating the southern tip of Manhattan. With the naval forces at their disposal, the Howes could land troops on either Long Island or Manhattan proper and send warships up either the East or Hudson Rivers a considerable distance.

Washington decided he must defend Brooklyn Heights on Long Island if he was to defend Manhattan; he therefore divided his army between the two places -- a violation of the principle of mass and the first step toward disaster. For all practical purposes command on Long Island was also divided. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, to whom Washington first entrusted the command, came down with malaria and was replaced by Maj. Gen. John Sullivan.

Not completely satisfied with this arrangement, at the last moment Washington placed Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam over Sullivan, but Putnam hardly had time to become acquainted with the situation before the British struck. The forces (in Long Island, numbering about 10,000, were disposed in fortifications on Brooklyn Heights and in forward positions back of a line of thickly wooded hills that ran across the southern end of the island. Sullivan was in command on the left of the forward line, Brig. Gen. William Alexander (Lord Stirling) on the right. Four roads ran through the hills toward the American positions. Unfortunately Sullivan, in violation of the principle of security, left the Jamaica-Bedford road unguarded.

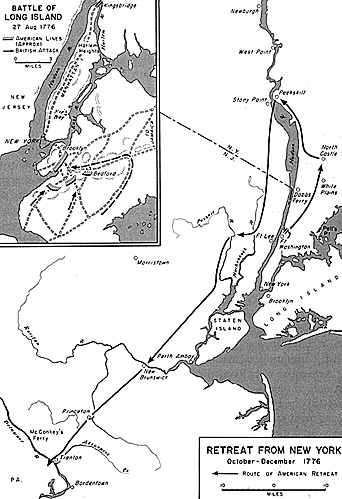

Howe was consequently able to teach the Americans lessons in maneuver and surprise. On August 22 he landed a force of 20,000 on the southwestern tip of Long Island and, in a surprise attack up the Jamaica-Bedford road against the American left flank, crumpled the entire American position. Stirling's valiant fight on the right went for naught, and inexperienced American troops fled in terror before the British and Hessian bayonets, falling back to the fortifications on Brooklyn Heights.

It seems clear that had Howe pushed his advantage immediately he could have carried the heights and destroyed half the American Army then and there. Instead he halted at nightfall and began to dig trenches, signaling an intent to take the heights by "regular approaches" in traditional eighteenth century fashion.

Washington managed to evacuate his forces across the East River on the night of August 29. According to one theory, wind and weather stopped the British warships from entering the river to prevent the escape; according to another, the Americans had placed impediments in the river that effectively barred their entry. In any case, it was a narrow escape, made possible by the skill, bravery, and perseverance of Col. John Glover's Marblehead Regiment, Massachusetts fishermen who manned the boats.

Washington had two weeks to prepare his defenses on Manhattan before Howe struck again, landing a force at Kip's Bay above the city of New York (now about 34th Street) on September 15. Raw Connecticut militia posted at this point broke and ran "as if the Devil was in them," defying even the efforts of a raging Washington to halt them.

Howe once again had an opportunity to split the American Army in two and destroy half, but again he delayed midway across the island to wait until his entire force had landed. General Putnam was able to bring the troops stationed in the city up the west side of Manhattan to join their Compatriots in new fortifications on Harlem Heights. There the Americans held out for another month, and even won a skirmish, but this position was also basically untenable.

In mid-October Howe landed again in Washington's rear at Pell's Point. The American commander then finally evacuated the Manhattan trap via Kingsbridge and took up a new position at White Plains, leaving about 6,000 men behind to man two forts, Fort Washington and Fort Lee, on opposite sides of the Hudson. Howe launched a probing attack on the American position at White Plains and was repulsed, but Washington, sensing his inability to meet the British in battle on equal terms, moved away to the north toward the New York highlands.

Again he was outmaneuvered. Howe quickly moved to Dobbs Ferry on the Hudson between Washington's army and the Hudson River forts. On the advice of General Greene (now recovered from his bout with malaria), Washington decided to defend the forts. At the same time he again split his army, moving across the Hudson and into New Jersey with 5,000 men and leaving General Lee and Mal. Gen. William Heath with about 8,000 between them to guard the passes through the New York highlands at Peekskill and North Castle.

On November 16 Howe turned against Fort Washington and with the support of British warships on the Hudson stormed it successfully, capturing 3,000 American troops and large quantities of valuable munitions. Greene then hastily evacuated Fort Lee and by the end of November Washington, with mere remnants of his army, was in full retreat across New Jersey with Lord Charles Cornwallis, detached by Howe, pursuing him rapidly from river to river.

While Washington was suffering these disastrous defeats, the army that had been gathered was slowly melting away. Militia left by whole companies and desertion among the Continentals was rife. When Washington finally crossed the Delaware into Pennsylvania in early December, he could muster barely 2,000 men, the hard core of his Continental forces. The 8,000 men in the New York highlands also dwindled away. Even more appalling, most enlistments expired with the end of the year 1776 and a new army would have to be raised for the following year.

Yet neither the unreliability of the militia nor the short period of enlistment fully explained the debacle that had befallen the Continental Army. Washington's generalship was also faulty. Criticism of the Commander in Chief, even among his official family, mounted, centering particularly on his decision to hold Fort Washington. General Lee, the ex-British colonel, ordered by Washington to bring his forces down from New York to join him behind the Delaware, delayed, believing that he might himself salvage the American cause by making incursions into New Jersey. He wrote Horatio Gates, entre nous, a certain great man is most damnably deficient . . . ...

There was only one bright spot in the picture in the autumn of 1776. While Howe was routing Washington around New York City, other British forces under Sir Guy Carleton were attempting to follow up the advantage they had gained in repulsing the attack on Canada earlier in the year. Carleton rather leisurely built a flotilla of boats to carry British forces down Lake Champlain and Lake George, intending at least to reduce the fort at Ticonderoga before winter set in.

Benedict Arnold countered by throwing together a much weaker flotilla of American boats with which he contested the British passage. Arnold lost this naval action on the lakes, but he so delayed Carleton's advance that the British commander reached Ticonderoga too late in the year to consider undertaking a siege. He returned his army to winter quarters in Canada, leaving the British with no advance base from which to launch the next year's campaign.

Although its consequences were to be far reaching, this limited victory did little to dispel the gloom that fell on the patriots after Washington's defeats in New York. The British, aware that Continental enlistments expired at the end of the year, had high hopes that the American Army would simply fade away and the rebellion collapse. Howe halted Cornwallis' pursuit of Washington and sent Clinton with a detachment of troops under naval escort to seize Newport, Rhode Island. He then dispersed his troops in winter quarters, establishing a line of posts in New Jersey at Perth Amboy, New Brunswick, Princeton, Trenton, and Bordentown, and retired himself to New York. Howe had gained the object of the 1776 campaign, a strong foothold, and possibly, as he thought at the time, a great deal more.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 2

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com