The major military operations of 1775 and early 1776 were not around Boston but in far-distant Canada, which the Americans tried to add as a fourteenth colony. Canada seemed a tempting and vulnerable target. To take it would eliminate a British base at the head of the familiar invasion route along the lake and river chain connecting the St. Lawrence with the Hudson. Congress, getting no response to an appeal to the Canadians to join in its cause, in late June 1775 instructed Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler of New York to take possession of Canada if "practicable" and "not disagreeable to the Canadians."

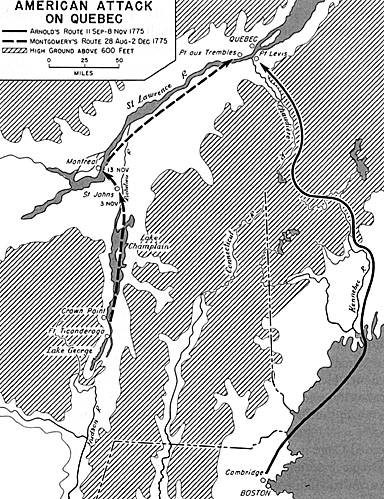

Schuyler managed to get together a force of about 2,000 men from New York and Connecticut, thus forming the nucleus of what was to become known as the Northern Army. In September 1775 Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery set out with this small army from Ticonderoga with the objective of taking Montreal. To form a second prong to the invasion, Washington detached a force of 1100 under Col. Benedict Arnold, including a contingent of riflemen under Capt. Daniel Morgan of Virginia, to proceed up the Kennebec River, across the wilds of Maine, and down the Chaudiere to join with Montgomery before Quebec.

Montgomery, advancing along the route via Lake George, Lake Champlain, and the Richelieu River, was seriously delayed by the British fort at St. Johns but managed to capture Montreal on November 13. Arnold meanwhile had arrived opposite Quebec on November 8, after one of the most rugged marches in history. One part of his force had turned back and others were lost by starvation, sickness, drowning, and desertion.

Only 600 men crossed the St. Lawrence on November 13, and in imitation of Wolfe scaled the cliffs and encamped on the Plains of Abraham. It was a magnificent feat, but the force was too small to prevail even against the scattered Canadian militia and British Regulars who, unlike Montcalm, shut themselves up in the city and refused battle in the open. Arnold's men were finally forced to withdraw to Point aux Trembles, where they were joined by Montgomery with all the men he could spare from the defense of Montreal --a total of 300. Nowhere did the Canadians show much inclination to rally to the American cause; the French habitants remained indifferent, and the small British population gave its loyalty to the governor general.

With the enlistments of about half their men expiring by the new year, Arnold and Montgomery undertook a desperate assault on the city during the night of December 30 in the middle of a raging blizzard. The Americans were outnumbered by the defenders, and the attack was a failure. Montgomery was killed and Arnold wounded.

The wounded Arnold, undaunted, continued to keep up the appearance of a siege with the scattered remnants of his force while he waited for reinforcements. The reinforcements came--Continental regiments raised in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania--but they came in driblets and there were never enough to build a force capable of again taking the offensive, though a total of 8,000 men were eventually committed to the Canadian campaign. Smallpox and other diseases took their toll and never did the supply line bring in adequate food, clothing, or ammunition.

Meanwhile, the British received reinforcements and in June 1776 struck back against a disintegrating American army that retreated before them almost without a fight. By mid-July the Americans were back at Ticonderoga where they had started less than a year earlier, and the initiative on the northern front passed to the British.

While the effort to conquer Canada was moving toward its dismal end, Washington finally took the initiative at Boston. On March 4, 1776, he moved onto Dorchester Heights and emplaced his newly acquired artillery in position to menace the city; a few days later he fortified Nook's Hill, standing still closer in. On March 17 the British moved out. It would be presumptuous to say that their exit was solely a consequence of American pressure.

Sir William Howe, who succeeded Gage in command, had concluded long since that Boston was a poor strategic base and intended to stay only until the transports arrived to take his army to Halifax in Nova Scotia to regroup and await reinforcements. Nevertheless, Washington's maneuvers hastened his departure, and the reoccupation of Boston was an important psychological victory for the Americans, balancing the disappointments of the Canadian campaign. The stores of cannon and ammunition the British were forced to leave behind were a welcome addition indeed to the meager American arsenal.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 2

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com