The American Revolution came about, fundamentally, because by 1763 the English-speaking communities on the far side of the Atlantic had matured to an extent that their interests and goals were distinct from those of the ruling classes in the mother country. British statesmen failed to understand or adjust to the situation. Ironically enough, British victory in the Seven Years' War set the stage for the revolt, for it freed the colonists from the need for British protection against a French threat on their frontiers and gave free play to the forces working for separation.

In 1763 the British Government, reasonably from its point of view, moved to tighten the system of imperial control and to force the colonists to contribute to imperial defense, proposing to station 10,000 soldiers along the American frontiers and to have the Americans pay part of the bill.

This imperial defense plan touched off the long controversy about Parliament's right to tax that started with the Stamp and Sugar Acts and ended in December 1773, when a group of Bostonians unceremoniously dumped a cargo of British tea into the city harbor in protest against the latest reminder of the British effort to tax. In this 10-year controversy the several British ministries failed to act either firmly enough to enforce British regulations or wisely enough to develop a more viable form of imperial union, which the colonial leaders, at least until 1776, insisted that they sought.

In response to the Boston Tea Party, the king and his ministers blindly pushed through Parliament a series of measures collectively known in America as the Intolerable Acts, closing the port of Boston, placing Massachusetts under the military rule of Mal. Gen. Sir Thomas Gage, and otherwise infringing on what the colonists deemed to be their rights and interests.

Since 1763 the colonial leaders, in holding that only their own popular assemblies, not the British Parliament, had a right to levy taxes on Americans, had raised the specter of an arbitrary British Government collecting taxes in America to support red-coated Regulars who might be used not to protect the frontiers but to suppress American liberties. Placing Massachusetts under military rule gave that specter some substance and led directly to armed revolt.

Outbreak

The First Continental Congress meeting at Philadelphia on September 5, 1774, addressed respectful petitions to Parliament and king but also adopted non-importation and non-exportation agreements in an effort to coerce the British Government into repealing the offending measures. To enforce these agreements, committees were formed in almost every county, town, and city throughout the colonies, and in each colony these committees soon became the effective local authorities, the base of a pyramid of revolutionary organizations with revolutionary assemblies, congresses, or conventions, and committees of safety at the top.

This loosely knit combination of de facto governments superseded the constituted authorities and established firm control over the whole country before the British were in any position to oppose them. The de facto governments took over control of the militia, and out of it began to shape forces that, if the necessity arose, might oppose the British in the field.

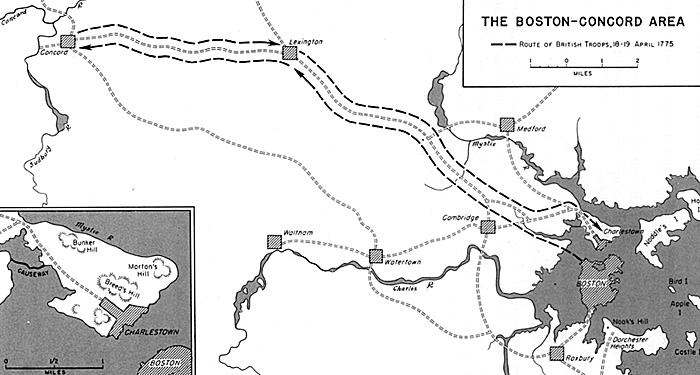

In Massachusetts, the seat of the crisis, the Provincial Congress, eyeing Gage's force in Boston, directed the officers in each town to enlist a third of their militia in Minutemen organizations to be ready to act at a moment's warning, and began to collect ammunition and other military stores. It established a major depot for these stores at Concord, about twenty miles northwest of Boston.

General Gage learned of the collection of military stores at Concord and determined to send a force of Redcoats to destroy them. His preparations were made with the utmost secrecy. Yet so alert and ubiquitous were the patriot eyes in Boston that when the picked British force of 700 men set out on the night of April 18, 1775, two messengers, Paul Revere and William Dawes, preceded them to spread the alarm throughout the countryside. At dawn on the 19th of April when the British arrived at Lexington, the halfway point to Concord, they found a body of militia drawn up on the village green.

Some nervous finger, whether of British Regular or American militiaman is unknown to this day, pressed a trigger. The impatient British Regulars, apparently without any clear orders from their commanding officer, fired a volley, then charged with the bayonet. The militiamen dispersed, leaving eight dead and ten wounded on the ground. The British column went on to Concord, destroyed such of the military stores as the Americans had been unable to remove, and set out on their return journey.

By this time, the alarm had spread far and wide, and both ordinary militia and Minutemen had assembled along the British route. From behind walls, rocks, and trees, and from houses they poured their fire into the columns of Redcoats, while the frustrated Regulars found few targets for their accustomed volleys or bayonet charges. Only the arrival of reinforcements sent by Gage enabled the British column to get back to the safety of Boston.

At day's end the British counted 273 casualties out of a total of 1,800 men engaged; American casualties numbered 95 men, including the toll at Lexington. What happened was hardly a tribute to the marksmanship of New England farmers--it has been estimated 75,000 shots poured from their muskets that day--but it did testify to a stern determination of the people of Massachusetts to resist any attempt by the British to impose their will by armed force.

The spark lit in Massachusetts soon spread throughout the rest of the colonies. Whatever really may have happened in that misty dawn on Lexington Green, the news that speedy couriers, riding horses to exhaustion, carried through the colonies from New Hampshire to Georgia was of a savage, unprovoked British attack and of farmers rising in the night to protect their lives, their families, and their property.

Lexington, like Fort Sumter and Pearl Harbor, furnished an emotional impulse that led all true patriots to gird themselves for battle. From the other New England colonies, militia poured in to join the Massachusetts men and together they soon formed a ring around Boston. Other militia forces under Ethan Allen of Vermont and Benedict Arnold of Connecticut seized the British forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, strategic positions on the route between New York and Canada. These posts yielded valuable artillery and other military stores. The Second Continental Congress, which assembled in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, found itself forced to turn from embargoes and petitions to the problems of organizing, directing, and supplying a military effort.

Before Congress could assume control, the New England forces assembled near Boston fought another battle on their own, the bloodiest single engagement of the entire Revolution. After Lexington and Concord, at the suggestion of Massachusetts, the New England colonies moved to replace the militia gathered before Boston with volunteer forces, constituting what may be loosely called a New England army. Each state raised and administered its own force and appointed a commander for it. Discipline was lax and there was no single chain of command.

Though Artemas Ward, the Massachusetts commander, exercised over-all control by informal agreement, it was only because the other commanders chose to co-operate with him, and decisions were made in council. While by mid-June most of the men gathered were volunteers, militia units continued to come and go. The volunteers in the Connecticut service were enlisted until December 10, 1775, those from the other New England states until the end of the year. The men were dressed for the most part in homespun clothes and armed with muskets of varied types; powder and ball were short and only the barest few had bayonets.

Late in May Gage received limited reinforcements from England, bringing his total force to 6,500 rank and file. With the reinforcements came three major generals of reputation--Sir William Howe, Sir Henry Clinton, and Sir John Burgoyne--men destined to play major roles in England's loss of its American colonies. The newcomers all considered that Gage needed more elbowroom and proposed to fortify Dorchester Heights, a dominant position south of Boston previously neglected by both sides. News of the intended move leaked to the Americans, who immediately countered by dispatching a force onto the Charlestown peninsula, where other heights, Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill, overlooked Boston from the north.

The original intent was to fortify Bunker Hill, the eminence nearest the narrow neck of land connecting the peninsula with the mainland, but the working party sent out on the night of June 16, 1775, decided instead to move closer in and construct works on Breed's Hill--a tactical blunder, for these exposed works could much more easily be cut off by a British landing on the neck in their rear.

The British scorned such a tactic, evidently in the mistaken assumption that the assembled "rabble in arms" would disintegrate in the face of an attack by disciplined British Regulars.

On the afternoon of the 17th, Gage sent some 2,200 of his men under Sir William Howe directly against the American positions, by this time manned by perhaps an equal force. Twice the British advanced on the front and flanks of the redoubt on Breed's Hill, and twice the Americans, holding their fire until the compact British lines were at close range, decimated the ranks of the advancing regiments and forced them to fall back and re-form. With reinforcements, Howe carried the hill on the third try but largely because the Americans had run short of ammunition and had no bayonets. The American retreat from Breed's Hill was, for inexperienced volunteers and militia, an orderly one and Howe's depleted regiments were unable to prevent the Americans' escape. British casualties for the day totaled a staggering 1,054, or almost half the force engaged, as opposed to American losses of about 440.

The Battle of Bunker Hill (for it was Bunker that gave its name to a battle actually fought on Breed's Hill) has been aptly characterized as a "tale of great blunders heroically redeemed." The American command structure violated the principle of unity of command from the start, and in moving onto Breed's Hill the patriots exposed an important part of their force in an indefensible position, violating the principles of concentration of force, mass, and maneuver.

Gage and Howe, for their parts, sacrificed all the advantages the American blunders gave them, violating the principles of maneuver and surprise by undertaking a suicidal attack on a fortified position.

Bunker Hill was a Pyrrhic victory, its strategic effect practically nil since the two armies remained in virtually the same position they had held before. Its consequences, nevertheless, cannot be ignored. A force of farmers and townsmen, fresh from their fields and shops, with hardly a semblance of orthodox military organization, had met and fought on equal terms with a professional British Army.

On the British this astonishing feat had a sobering effect, for it taught them that American resistance was not to be easily overcome; never again would British commanders lightly attempt such an assault on Americans in fortified positions. On the Americans, the effect was hardly sobering, and in the long run was perhaps not salutary. Bunker Hill, along with Lexington and Concord, went far to create the American tradition that the citizen soldier when aroused is more than a match for the trained professional, a tradition that was to be reflected in American military policy for generations afterward.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 2

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com