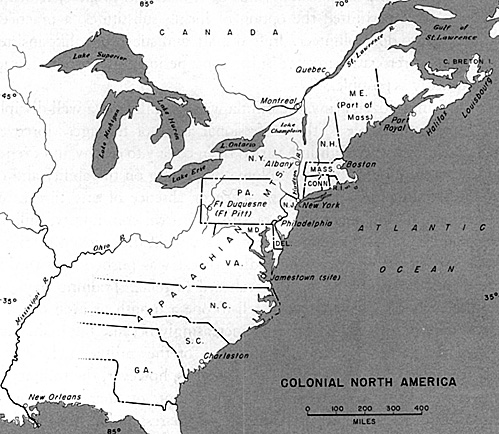

While England was colonizing the eastern seaboard from Maine to

Georgia, France was extending its control over Canada and Louisiana and asserting its claim to the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi Valley in the rear of the British colonies. Spain held Florida, an outpost of its vast colonial domains in Mexico, Central and South America, and the West Indies. England and France were invariably on opposite sides in the four great dynastic coalition wars fought in Europe between 1689 and 1763. Spain was allied with France in the last three of these conflicts. Each of these European wars bad its counterpart in a struggle between British and French and Spanish colonists in America, intermingled with a quickening of Indian warfare all along the frontiers as the contestants tried to use the Indian tribes to their advantage.

While England was colonizing the eastern seaboard from Maine to

Georgia, France was extending its control over Canada and Louisiana and asserting its claim to the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi Valley in the rear of the British colonies. Spain held Florida, an outpost of its vast colonial domains in Mexico, Central and South America, and the West Indies. England and France were invariably on opposite sides in the four great dynastic coalition wars fought in Europe between 1689 and 1763. Spain was allied with France in the last three of these conflicts. Each of these European wars bad its counterpart in a struggle between British and French and Spanish colonists in America, intermingled with a quickening of Indian warfare all along the frontiers as the contestants tried to use the Indian tribes to their advantage.

Americans and Europeans called these wars by different names. The War of the League of Augsburg (1689-97) was known in America as King William's War, the War of Spanish Succession (1701-13) as Queen Anne's War, the War of Austrian Succession (1744-48) as King George's War, and the final and decisive conflict, the Seven Years' War (1756-63), as the French and Indian War. In all of these wars one of the matters involved was the control of the North American continent; in the last of them it became the principal point at issue in the eyes of the British Government.

The main centers of French strength were along the St. Lawrence River in Canada-Quebec and Montreal-and the strategic line along which much of the fighting took place in the colonies lay between New York and Quebec, either on the lake and river chain that connects the Hudson with the St. Lawrence in the interior or along the seaways leading from the Atlantic up the St. Lawrence. In the south, the arena of conflict lay in the area between South Carolina and Florida and Louisiana. In 1732 the British Government established the colony of Georgia primarily as a military outpost in this region.

In the struggle for control of North America, the contest between England and France was the vital one, the conflict with Spain, a declining power, important but secondary. This latter conflict reached its height in the "War of Jenkins Ear," a prelude to the War of Austrian Succession, which began in 1739 and pitted the British and their American colonists against the Spanish.

In the colonies the war involved a seesaw struggle between the Spanish in Florida and the West Indies and the English colonists in South Carolina and Georgia. Its most notable episode, however, was a British expedition mounted in Jamaica against Cartagena, the main port of the Spanish colony in Colombia. The mainland colonies furnished a regiment to participate in the assault as British Regulars under British command. The expedition ended in disaster, resulting from climate, disease, and the bungling of British commanders, and only about 600 of over 3,000 Americans who participated ever returned to their homes. The net result of the war itself was indecisive.

The first three wars with the French were also indecisive. The nature of the fighting in them was much the same as that in the Indian wars. Although the French maintained garrisons of Regulars in Canada, they were never sufficient to bear the brunt of the fighting. The French Canadians also had their militia, a more centralized and all-embracing system than that in the English colonies, but the population of the French colonies was sparse, scarcely a twentieth of that of the British colonies in 1754. The French relied heavily on Indian allies, whom they equipped with firearms. They were far more successful than the British in influencing the Indians, certainly in part because their sparse population posed little threat to Indian lands.

The French could usually count on the support of the Indian tribes in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions, though the British colonists did maintain greater influence with the powerful Iroquois confederacy in New York. The French constructed forts at strategic points and garrisoned them with small numbers of Regulars, a few of whom they usually sent along with militia and Indian raiding parties to supervise operations. Using guerrilla methods, the French gained many local successes and indeed kept the frontiers of the English colonies in a continual state of alarm, but they could achieve no decisive results because of the essential weakness of their position.

The British and their colonists usually took the offensive and sought to strike by land and sea at the citadels of French power in Canada. The British Navy's control of the sea made possible the mounting of sea expeditions against Canada and at the same time made it difficult for the French to reinforce their small Regular garrisons. In 171o a combined British and colonial expedition captured the French fort at Port Royal on Nova Scotia, and by the treaty of peace in 1713 Nova Scotia became an English possession.

In 1745 an all-colonial expedition sponsored by Massachusetts captured Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island in what was perhaps the greatest of colonial military exploits, only to have the stronghold bargained away in 1748 for Madras, a post the French had captured from the British in India.

While militia units played an important part in the colonial wars, colonial governments resorted to a different device to recruit forces for expeditions outside their boundaries such as that against Louisbourg. This was the volunteer force, another institution that was to play an important part in all American wars through the end of the nineteenth century.

Unlike the militia units, volunteer force's were built from the top down. The commanding officers were first chosen by one of the colonial governors or assemblies and the men were enlisted by them. The choice of a commander was made with due regard for his popularity in the colony since this was directly related to his ability to persuade officers and men to serve under him. While the militia was the main base for recruitment, and the officers were almost invariably men whose previous experience was in the militia, indentured servants and drifters without military obligation were also enlisted. The enlistment period was only for the duration of a campaign, at best a year or so, not for long periods as in European armies. Colonial assemblies had to vote money for pay and supplies, and assemblies were usually parsimonious as well as unwilling to see volunteer forces assume any of the status of a standing Regular Army. With short enlistments, inexperienced officers, and poor discipline by European standards, even the best of these colonial volunteer units were, like the militia, often held in contempt by British officers.

The only positive British gain up to 1748 was Nova Scotia. The indecisive character of the first three colonial 'Wars was evidence of the inability of the English colonies to unite and muster the necessary military forces for common action, of the inherent difficulty of mounting offensives in unsettled areas, and of a British preoccupation with conflicts in Europe and other areas.

Until 1754 the British Government contented itself with maintaining control of the seas and furnishing Regulars for sea expeditions against French and Spanish strongholds; until 1755 no British Regulars took part in the war in the interior, though small "independent companies" of indifferent worth were stationed continuously in New York and occasionally in other colonies. No colony, meanwhile, was usually willing to make any significant contribution to the common cause unless it appeared to be in its own interest. Efforts to form some kind of union, the most notable of which was a plan advanced by Benjamin Franklin in a colonial congress held at Albany in 1754, all came to naught.

Between 1748 and 1754 the French expanded their system of forts around the Great Lakes and moved down into the Ohio Valley, establishing Fort Duquesne at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in 1753 and staking a claim to the entire region. In so doing, they precipitated the final and decisive conflict which began in America two years before the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in Europe.

Braddock's Expedition

In 1754 Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia sent young George Washington at the head of a force of Virginia militia to compel the French to withdraw from Fort Duquesne. Washington was driven back and forced to surrender. The British Government then sent over two understrength regiments of Regulars under Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock, a soldier of some forty-five years' experience on continental battlefields, to accomplish the task in which the militia had failed.

In 1754 Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia sent young George Washington at the head of a force of Virginia militia to compel the French to withdraw from Fort Duquesne. Washington was driven back and forced to surrender. The British Government then sent over two understrength regiments of Regulars under Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock, a soldier of some forty-five years' experience on continental battlefields, to accomplish the task in which the militia had failed.

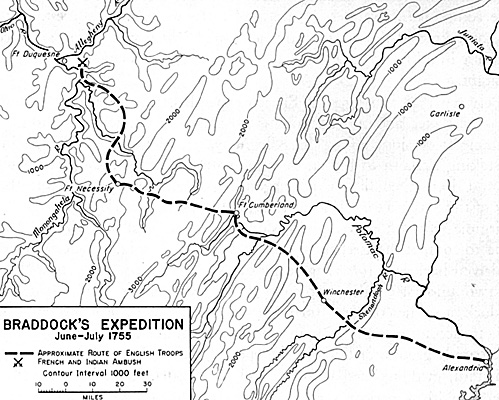

Accustomed to the parade ground tactics and the open terrain of Europe, Braddock placed all his faith in disciplined Regulars and close order formations. He filled his regiments with American recruits and early in June 1755 set out on the long march through the wilderness to Fort Duquesne with a total force of about 2,200, including a body of Virginia and North Carolina militiamen. George Washington accompanied the expedition, but had no command role.

Braddock's force proceeded westward through the wilderness in traditional column formation with 300 axmen in front to clear the road and a heavy baggage train of wagons in the rear. The heavy wagon train so slowed his progress that about halfway he decided to let it follow as best it could and went ahead with about 1,300 selected men, a few cannon, wagons, and packhorses.

As he approached Fort Duquesne, he crossed the Monongahela twice in order to avoid a dangerous and narrow passage along the east side where ambush might be expected. He sent Lt. Col. Thomas Gage with an advance guard to secure the site of the second crossing, also deemed a most likely spot for an ambush. Gage found no enemy and the entire force crossed the Monongahela the second time on the morning of July 9, 1755, then confidently took up the march toward Fort Duquesne, only seven miles away.

About three quarters of a mile past the Monongahela crossing, Gage's advance guard suddenly came under fire from a body of French and Indians concealed in the woods. Actually it was a very inferior force of 70 French Regulars, 150 Canadian militia (many mere boys), and 650 Indians who had just arrived on the scene after a hasty march from Fort Duquesne. Some authorities think Gage might have changed the whole course of the battle had he pushed forward, forcing the enemy onto the open ground in their rear.

Instead he fell back on the main body of Braddock's troops, causing considerable confusion. This confusion was compounded when the French and Indians slipped into the forests on the flanks of the British troops, pouring their fire into a surprised and terrified mass of men who wasted their return volleys on the air. "Scarce an officer or soldier," wrote one of the participants, "can say they ever saw at one time six of the enemy and the greatest part never saw a single man."

None of the training or experience of the Regulars had equipped them to cope with this sort of attack, and Braddock could only exhort them to rally in conventional formation. Two-thirds of his officers fell dead or wounded. The militia, following their natural instincts, scattered and took positions behind trees, but there is no evidence they delivered any effective fire, since French and Indian losses for the day totaled only 23 killed and 16 wounded.

The few British cannon appear to have been more telling. Braddock, mortally wounded himself, finally attempted to withdraw his force in some semblance of order, but the retreat soon became a disordered flight. The panic-stricken soldiers did not stop even when they reached the baggage wagons many miles to their rear.

Despite the completeness of their victory, the French and Indians made no attempt to follow it up. The few French Regulars had little control over the Indians, who preferred to loot the battlefield and scalp the wounded. The next day the Indians melted back into the forest, and the French commandant at Duquesne noted in his official report: "If the enemy should return with the 1,000 fresh troops that he has in reserve in the rear, at what distance we do not know, we should perhaps be badly embarrassed." The conduct of the battle was not so reprehensible as the precipitate retreat of the entire force back to the safety of the settled frontiers, when no enemy was pursuing it.

Although Braddock had been aware of the possibilities of ambush and had taken what he thought were necessary precautions, in the broader sense he violated the principles of security and maneuver; for when the ambush came he had little Idea how to cope with Indian tactics in the forest.

As he lay dying on the wagon that transported him from the battlefield, the seemingly inflexible old British general is alleged to have murmured, "Another time we shall know better how to deal with them."

Braddock's Defeat

Braddock's Defeat

Braddock could not profit from his appreciation of the lesson but the British Army did. "Over the bones of Braddock," writes Sir John Fortescue, the eminent historian of the British Army, "the British advanced again to the conquest of Canada."

After a series of early reverses, of which Braddock's disastrous defeat was only one, the British Government under the inspired leadership of William Pitt was able to achieve a combination of British and colonial arms that succeeded in overcoming the last French resistance in Canada and in finally removing the French threat from North America. In this combination British Regular troops, the British Navy, British direction, and British financial support were the keys to victory; the colonial effort, though considerable, continued to suffer from lack of unity.

As an immediate reaction to Braddock's defeat, the British Government sought to recruit Regulars in America to fight the war, following the precedent set in the Cartagena expedition. Several American regiments were raised, the most famous among them Col. Henry Bouquet's Royal Americans. On the whole, however, the effort was a failure, for most Americans preferred short service in the militia or provincial volunteer forces to the long-term service and rigid discipline of the British Army.

After 1757 the British Government under Pitt, now convinced that America was the area in which the war would be won or lost, dispatched increasing numbers of Regulars from England--a total of 20,000 during the war. The British Regulars were used in conjunction with short-term militia and longer term volunteer forces raised in the service of the various individual colonies.

The British never hit upon any effective device to assure the sort of colonial co-operation they desired and the burdens of the war were unequally divided since most colonies did not meet the quotas for troops, services, and supplies the British Government set. Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York furnished about seven-tenths of the total colonial force employed.

The British found it necessary to shoulder the principal financial burden, reimbursing individual colonies for part of their expenses and providing the pay and supply of many of the colonial volunteer units in order to insure their continued service.

Braddock's defeat was not repeated. In no other case in the French and Indian War was an inferior guerrilla force able to overcome any substantial body of Regulars. The lessons of the debacle on the Monongahela, as the British properly understood, were not that Regular forces or European methods were useless in America or that undisciplined American militia were superior to Regular troops. They were rather that tactics and formations had to be adapted to terrain and the nature of the enemy and that Regulars, when employed in the forest, would have to learn to travel faster and lighter and take advantage of cover, concealment, and surprise as their enemies did. Or the British could employ colonial troops and Indian allies versed in this sort of warfare as auxiliaries, something the French had long since learned to do.

The British adopted both methods in the ensuing years of the French and Indian War. Light infantry, trained as scouts and skirmishers, became a permanent part of the British Army organization. When engaged in operations in the forest, these troops were clad in green or brown clothes instead of the traditional red coat of the British soldier, their heads shaved and their skins sometimes painted like the Indians'. Special companies, such as Maj. Robert Rogers' Rangers, were recruited among skilled woodsmen in the colonies and placed in the Regular British establishment.

Despite this employment of light troops as auxiliaries, the British Army did not fundamentally change its tactics and organization in the course of the war in America. The reduction of the French fortress at Louisbourg in 1758 was conducted along the classic lines of European siege warfare. The most decisive single battle of the war was fought in the open field on the Plains of Abraham before the French citadel of Quebec.

In a daring move, Maj. Gen. James Wolfe and his men scaled the cliff s leading up to the plain on the night of September 12, 1759, and appeared in traditional line of battle before the city the next morning. Major General the Marquis de Montcalm, the able French commander, accepted the challenge, but his troops, composed partly of militia levies, proved unable to withstand the withering "perfect volleys" of Wolfe's exceptionally well-disciplined regiments.

The ultimate lesson of the colonial wars, then, was that European and American tactics each had its place, and either could be decisive where conditions were best suited to its use. The colonial wars also proved that only troops possessing the organization and discipline of Regulars, whatever their tactics, could actually move in, seize, and hold objectives, and thus achieve decisive results.

Other important lessons lay in the realm of logistics, where American conditions presented difficulties to which European officers were unaccustomed. The impediments to supply and transport in a vast, undeveloped, and sparsely populated country limited both the size and variety of forces employed. The settled portions of the colonies produced enough food, but few manufactured goods.

Muskets, cannon, powder, ball, tents, camp kettles, salt, and a variety of other articles necessary for even the simple military operations of the period almost all had to come from Europe. Roads, even in the settled areas, were poor and inadequate; forces penetrating into the interior had to cut their roads as they went, as Braddock did.

These logistical problems go far to explain why the fate of America was settled in battles involving hardly one-tenth the size of forces engaged in Europe in the Seven Years' War, and why cavalry was almost never employed and artillery to no great extent except in fixed fortifications and in expeditions by sea when cannon could be transported on board ship. The limited mobility of large Regular forces, whatever the superiority of their organization and tactics, put a premium both on small bodies of trained troops familiar with the terrain and on local forces, not so well trained, already in an area of operations. Commanders operating in America would ignore these logistical limitations at their peril.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 1

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com