Going back 348 years, Marston Moor has changed little since. Back then it was host to the largest battle on English soil and its result would decide who would reign supreme in the North of England. That the battle occurred in the first place was decided by several strokes of fate.

When Parliament invited a foreign power, Scotland, to enter the war, this immediately put the superior Northern Royalists under the Marquis of Newcastle under immense strain.

Newcastle had trounced the Parliamentarians under the Fairfaxes, a father and son duo. The entry of the rough Scots and their huge numbers made it impossible for Newcastle to remain on the offensive and keep his gains.

He eventually was forced to retreat back far North to confront the Scots who were approaching Newcastle, but he was outnumbered and retreated.

He entered his headquarters in York, sending Lord Goring and all his cavalry to the King with an elegant plea for help. Newcastle despite being a poet and a connoisseur of learning, knew his military art well. Now in York, three huge armies were gradually strangulating him.

Lord Manchester from the Eastern Association, Lord Fairfax and his Yorkshiremen and the new Scot’s had joined to single York out. Help was already at hand in the form of a well-known saviour, Prince Rupert. If the King’s nephew could not save York, then nobody could and the Parliamentarians had become nervous by the news of his approach.

Rupert’s March to the Battle

Rupert marched towards the city and at the last moment, turned sharply to the north of York, which was left unguarded. Marching into the city unopposed, he relieved the city, but marched next day towards the enemy for a battle. At this point, the Royalists had a number of ways which they could trounce their enemies:

Newcastle’s subordinate Lord Eythin made Rupert’s plans stillborn and the Royalists lost the initiative.

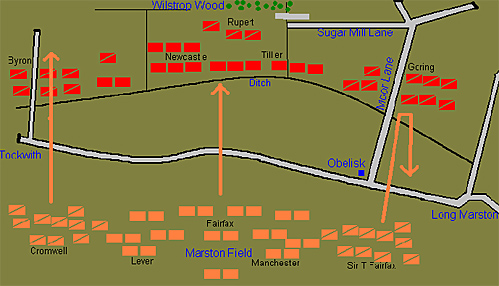

The battle was throughout a knife-edge, despite the severe weight of numbers favouring the Parliamentarians. There were 18,000 Royalists facing roughly 24,000 of their opponents.

Rupert chose his ground well, opting for a defensive position, fully utilising the ground which still remains in place today, as a visible reminder. Feeling safe in their positions, the Royalists did not imagine that at around late evening, a clap of thunder could herald a late Parliamentarian offensive.

The Royalist right wing of horse clashed and fled, while Rupert tried unsuccessfully to rally them, while his left wing cut through the enemy Parliamentarians. In the middle, the Royalist foot proved superior, beginning to push their opponents back. This prompted two of the three senior Parliamentarian commanders to flee.

Things looked bleak, but Sir Thomas Fairfax of the defeated Parliamentary right wing, rode to Cromwell’s victorious horse for help and together they rode around the Royalist foot, scattering the remaining horsemen, before carving into the exposed foot regiments.

After a heroic last stand by the Marquis of Newcastle’s Whitecoats, they were killed to the last man and the battle was over.

Today’s Field

348 years of change has not affected the layout and appearance of the battlefield much since. On the Royalist part of the field, you can still see the furze, ditch and hedges, which lined their defensive position, together with the woods, which framed the last stand of the Whitecoats. It is still said that musket balls can be picked up from the site of this heroic stand, even today.

On the Parliamentarian side, the high ground and the field can be seen with its distinctive crowning feature, Cromwell’s plump. This is an old and crooked tree, which stands on the hill and is where all the Roundhead Generals conferred before the offensive, although it has no relation to Cromwell himself.

A Monument stands erected just in front of the Royalist positions, where the road passes from Long Marston to Tockwith. Put up by the Cromwell Association, it boasts in its engravings, that Cromwell’s men beat the forces of Prince Rupert. Of course Cromwell was in no way the senior commander, the army was in fact the Scottish Lord Leven’s.

Moor Lane, a track which led through the fields still winds its way down the field, hemmed in by ditches and hedges either side, still having a fork in it once you reach the end, just like the old plans show from the period.

It feels quite unreal as though nothing has changed there, so much so that many of the old soldiers have not left the field even now.

Many locals report occurrences from several different places around the field. One told the story of a late night drive, not past the battlefield, but through the area surrounding it.

The man described how he saw two men, one holding the other up as though wounded, but dressed with large boots and white shirt. Thinking they were drunken fancy dress goers, he thought nothing of it until when he looked into his mirror and they had vanished.

Another woman spotted a headless horseman riding through the fields where the Parliamentary armies stood, whilst others report soldiers hiding in ditches and behind hedges. A picture of the fugitive Royalists hiding for their lives comes to mind, trying to make their way back to York after the defeat.

In fact as I drove to the field, the weather echoed the original crackle of thunder and pelting rain. After the summer squall had passed over, I examined the obelisk and looked back towards Rupert’s command post and then Cromwell’s plump in the Parliamentary lines. There is and was less than a mile separating the two command posts with 900 yards separating the two armies.

As you trace your way up the muddy moor lane, you can see the still distinct form of the path leading right through where Goring’s cavalry had stood, right to the fork which leads to Rupert’s post. Wilstrop Wood lies further on, behind Royalist lines and some say it was the final ground of the brave Whitecoats.

Others however maintain the historic point of the last stand as being in White Sykes Close. One TV presenter actively disputed this when he walked past White Sykes Close onto Wilstrop Wood, gathering up a handful of musket balls, which apparently still litter this wooded part of the field. This he claimed was proof that so many bullets in one area, meant that this was in fact the location of the Whitecoats last stand, making sense with having the woods to their immediate backs, to protect from the cavalry.

Understanding any battle is much easier if you visit the site, see the distances and ground involved and this enables you to relate to the description of the battle itself. Today Marston Moor is still in use by the nearby farm, though Moor Lane remains open to the public.

After one of my own recent visits, I tried to plot out the places and find some musket balls of my own. After thinking myself lucky, I realised I had in fact stumbled across none other than rabbit droppings!

Marston Moor is a couple of miles from the historic City of York, in picturesque countryside. Most anniversaries, 2nd July 1644, re-enactment societies replay the battle on the field, provided an exhilarating and historic sight.

Like what you read - go to King or Parliament Magazine for more, where

you can vote for which side you would have supported 360 years ago.

Suggested Reading

Marston Moor 1644, Peter Young - 1997

A Battlefield Atlas of the English Civil War, Anthony Baker - 1986

Map

Note: Mark Turnbull is the editor of King or Parliament, an ECW newsletter exclusively available on MagWeb.com.--RL

Back to List of Battlefields

Back to Travel Master List

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 2002 by Mark Turnbull.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com