In response to a trickle of inquiries from hard core War Between The States fans

(sometimes known as The War Of The Great Rebellion) we are presenting another group of

Confederate flags from the War Department Attic Collection sent home by Theodore Roosevelt.

In response to a trickle of inquiries from hard core War Between The States fans

(sometimes known as The War Of The Great Rebellion) we are presenting another group of

Confederate flags from the War Department Attic Collection sent home by Theodore Roosevelt.

First, however, at the risk of offending some of the very people who have asked for this article I would like to digress for some remarks on the composition and nature of some of the units involved, or more properly, some of the organizational types involved in what must rank as the most serious of our nation's wars. (If the Northeastern Liberal Establishment had been willing to quit at 50,000 fatalities out of a much smaller population back in those days, we'd have been independent long before the battle of Gettysburg!)

When war came in 1861, the regular army had a regimental organization essentially similar to that described by James Hinds for the Mexican War. Those familiar with continental wars of the Napoleonic era will recognize the ten company battallion- regiment as a distinctly British institution. However, in the United States, probably in order to permit the cavalry to operate as infantry when Congress decided not to appropriate money for horses, the 1st Dragoons, 2nd Dragoons, Mounted Rifles, and 1st and 2nd Cavalry regiments were of similar structure. Of these mounted regiments, the 2nd Cavalry was probably among the best mounted and equipped. It was composed largely of southern aristocrats during Jefferson Davis' term as secretary of war, and was sometimes referred to as "Jeff Davis's Own."

The 2nd "Jeff Davis's Own" Cavalry had the good fortune, if memory serves correctly, to pull off a rather spectacular saber charge against a far larger number of Indians in the Pacific Northwest. You will probably read from time to time that sabers were useless against Indians, Confederates, Yankees, and all sorts of people. Sheridan's Valley campaign, alas, made clear that a mounted charge with drawn sabers could at times discourage even Confederate infantry. Stuart once bluffed a Federal infantry force to abandon a ford by threatening a charge, but the Northwestern tribesmen really had the worst of it.

A few years before the War Between the States a large force of Indian Warriors had gathered to contest the presence of the 2nd Cavalry on their traditional hunting grounds. To inspire the troops, some wag of a medicine man had sold his followers on the notion that while wearing "ghost shirts," they would be invulnerable to bullets. Once on the field, the cavalry wheeled into line, and was given the order to draw saber and charge. It is easy to imagine the consternation of the warriors at that moment! The better part of a thousand disciplined troops crossing the plains in line without firing a shot, all bugles, guidons, and flashing blades, when it occurred to the Indians that their prescription was an antidote only to the bullets! Seeing that the white-eyes were on to their scheme, the warriors took to their heels and scattered in all directions.

There may have been something to the good doctor's medicine. It is recorded that in the pursuit that followed, one unsportsmanlike old chief went for his revolver and opened fire. He had dismounted to steady his aim, and since the days of Plato troopers engaged in pursuit have tended to avoid cantankerous and well armed veterans in favor of fugitives. One officer did dismount, and tried to return fire with his own revolver, but it misfired, (Say what you will about ghost shirts, this one worked.) Lt. Stuart (later Major General Stuart, C.S.A.) decided to do it the hard way, and rode the chief down saber in hand. The chief hit him in the chest finally, but Stuart closed too fast and whacked him over the head before he fell. (As we have already suggested, ghost shirts had a limited efficacy, and the wounded chief was captured. War Between the States buffs are aware that J.E.B. Stuart went on to greater things until killed by another revolver shot, this time from another dismounted retreating horseman, at Yellow Tavern.)

At any rate, when the war broke out, the list to 5th mounted regiments, in order of seniority, were all classed as cavalry. A 6th Cavalry regiment of the regular army was also raised, and between the reclassification of the existing mounted units and the raising of the new regiment, a reform was introduced increasing the strength of each cavalry regiment to 12 troops, or companies, as they were then called. Most Federal volunteer cavalry regiments are supposed to have followed suit. Confederate cavalry probably maintained 10 troops in many cases. Often, however, a separate detachment of sharpshooters was formed, and a "Company Q" of dismounted troopers awaiting captured remounts because the horses they had brought from home had been killed in action. A Confederate cavalry regiment was not necessarily weaker in total numbers, however, because the Confederacy followed a policy of sending replacements to active units while the Northern policy was one of raising fresh units so as to find employment for additional political colonels. (This historical fact is at complete variance with the established tradition of southern colonels, a disparity which I am at complete loss to explain.)

Another reform in the cavalry occurred when the United States Congress, War Department, etc. concluded that shoulder arms for the cavalry were superfluous. Up through the Seven Days, Yankee horsemen in the Army of the Potomac carried only sabers and revolvers. Of course, the 6th Pennsylvania carried lances too, but they were unusual. During Stuart's first raid an incident occurred which is supposed to have underscored the need for carbines in the Federal Cavalry. Actually, it didn't.

A regiment of regular U.S. Cavalry had a force blocking Stuart's route under the command of a captain. The captain, when writing about the incident later stated that he had drawn up his men in line with drawn revolver to face the Confederate onslaught, but was helpless before the mass of charging troopers bearing rifles, carbines, fowling pieces, etc. As it turned out, the captain in question was wounded in the head and captured. After all, what chance did the poor man have with all that buckshot and stuff flying around? It may be unkind to mention it, but the wound was from a saber.

The leading Confederate officer, one Latane, rode through a heavy barrage of revolver fire to deal the wound, and was killed by a total of five pistol balls. Latane was reportedly the only Confederate killed in action during Stuart's ride around McClellan.

With twelve troops becoming standard in the Federal Cavalry, and with independent companies of horse being common early in the war, especially south of the Mason-Dixon Line, a new phenomenon occurred in cavalry organization: Cavalry Battalions. Originally each two companies of cavalry became a squadron. In practice, however, the squadron, especially with Confederate shortages of menand horses, and the curious Federal habit of never (or rarely) feeding reinforcements into active regiments, proved too small for independent operation, so the cavalry formed battalions.

Each battalion was composed of four companies, thus three to regiment of twelve companies (e.g. Custer, Reno, and Benteen at you know where.) The battalion nominally consisted of over 400 officers and men. In practice this high number probably never occurred. Much later, probably around the turn of the century, battalions of cavalry were renamed squadrons, and an upgraded company, numbering about the strength of an infantry company of World War I was known as a troop. In spite of the cavalry nomenclature, the U.S. cavalry always fitted closely the organizational structure of infantry, at least as compared to European tradition.

Thus while a U.S. Cavalry regiment was about equal in "paper strength" to a U.S. infantry regiment, a German cavalry regiment was equal to about 1/5th of a German infantry regiment. By World War II, when Patton asked for U.S. cavalry to operate in the Italian mountains, a plan was drafted to send a French Spahi Brigade, equal in numbers to a U.S. cavalry regiment. (it was never sent, so the allies made do with ersatz mounted reconnaissance companies and pack mule units.)

Flags

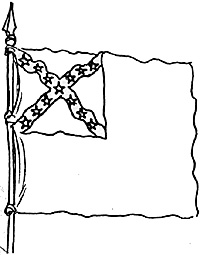

What was this article about? Oh yes! Flags! Our first flag this issue is the headquarters flag of General Jubal Early, Corps Commander in The Army of Northern Virginia, 1864-1865. It is a perfectly standard "Stainless Banner," next to the last of official Confederate national flags. White field with the "Battle Flag" in the corner. Early ran this flag up and down the Shenandoah Valley, at one point skirmishing with the Washington fortifications, until practically ridden into the ground by General Sheridan's barbaric hordes. (Early complained that the Confederate cavalry had forgotten how to fight mounted with the saber and were therefore out-matched when they tried to oppose Sheridan's troopers by dismounting with the carbines-which true cavalrymen have always known blighted the offensive spirit of the arm.)

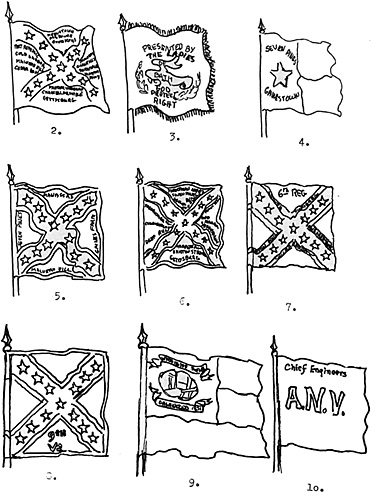

The second flag is that of the 1st Texas Infantry, originally Hood's Brigade, Jackson's Corps, Army of Northern Virginia. It appears to be a standard pattern battle flag except that the usual white border on the blue St. Andrews cross is missing. The battle honors of the Army of Northern Virginia, including Jackson's valley excursions, are in blue letters on the red field.

The third flag is identified only as the "Bath Company Flag." The design is weird, having a mis-shapen scroll, in white, laurels of green, field of blue, and lettering white on blue, blue on white. The lettering serves to identify the manufacturers prominently at the top, and gives God certain orders of the day as a post-script at the bottom. (No doubt they meant well).

The fourth flag is identified only as a flag of Hood's Texas Brigade. The union is blue, lone star, of course, in white, as are the words "Seven Pines," and "Gainestown." The bands are red on top, white on bottom. Although no comments to the effect were contained in the U.D.C. and U.C.V. booklet, this may have been a remnant of a Stars and Bars pattern flag turned in when the Battle Flag came out or was captured in the Seven Days.

The fifth and sixth flags are of the 2nd and 48th Mississippi Regiments, Army of Northern Virginia. They are both of Battle Flag pattern with battle honors blue on red.

The seventh is the flag of the 6th Kentucky Infantry, "Orphan" Brigade, Army of Tennessee. The regimental numeral is in white, Shiloh, Vicksburg, Baton Rouge, Murfreesboro, and Chickamauga written in black on the white lines of the St. Andrews Cross.

The eighth flag is a standard pattern, 9th Virginia Infantry, white lettering. This one has the advantage of being easy to paint in 23mm scale.

Number 9 is the flag of the Washington Rifles of Georgia. In lieu of stars the blue union has what appears to be a pillored manse (perhaps an odd view of Mt. Vernon) and two scrolls, the regimental identification on top, "Organized 1851 " at the bottom, indicating that the unit was a pre-war militia unit mustered into Confederate service (or into Governor Joe Brown's Draft Dodgers for all I know.)

Last of all is the red personal banner of the Chief of Engineers, Army of Northern Virginia, so indicating in white letters.

Back to The Armchair General Vol. 2 No. 8 Table of Contents

Back to The Armchair General List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1970 by Pat Condray

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com