Somewhere in every good Swiss mercenary's contract, it is said, there was once a small clause, maybe in fine print, which read, "the enlistee is not bound to take part in siege operations of any sort." Why would the iron- nerved Swiss who usually feared only God and the Devil quail before the dangers of the siege? Maybe there was just something about the prospect of having people who were themselves behind cover shooting at you that made any attack on fortifications seem foolhardy. (It still seems foolhardy to some despite the fact that a Frenchman named Sibastien Le Prestre de Vauban brought siege-craft to the level of an art.

Siegecraft is a method of capturing strongholds that is faster than blockade or starvation and slower than a coup de main or a successful sudden assault. As practiced from the Seventeenth through the Nineteenth centuries the art was very methodical in nature, a fact which ought to make the siege a good subject for wargaming. On the other bane, Riven a proper ratio of forces there is a certain inevitability in siege operations (Place a siege, place prise), and perhaps this very inevitability discourages the wargamer from the siege pare. However, there is no need to let this spoil your sport. Make time the key factor.

Although anyone with unlimited resources could capture any place, there was no guarantee as to how long it would take. The attacker right have his enemy's fort in less than a week or he might be compelled to spend months in tedious operations. Meanwhile the whole character of a war could change. Armies could be set in motion, alliances could be concluded and so on. The besieger might well find himself forced to abandon his protracted siege in order to defend his own country.

Normally, the besieger needed at least a three to one superiority in manpower and a two to one superiority in guns in order to take a fortification. This was for the actual attack forces and does not include other troops which might be needed In connection with a siege.

If a fortification were weakly held a surprise or a direct attack might well be preferred as less costly and time consuming than a siege. Usually the assault force would be equipped with ladders for this purpose. Generally such a force consisted of three elements, an advanced Party or forelorn hope, usually consisting of volunteers, grenadiers, or sappers. A column of attack, of varying strength and a reserve usually of greater strength. Such an attack right be called an escalade, when directed against a permanent fort. Direct attacks that failed were often quite costly.

If a fortification were too strong to take by storm, then a siege might be the best method of reducing it. First of all the attacker invested or surrounded it. In order to prevent and relief from reaching the besieged. The attacker might station an army of observation, frequently strong in cavalry, in a position between the interior of the enemy's country and the besieging forces.

After the initial stage of investment the attacker began his preparations for the next phase. Siege guns were brought up and formed into a large artillery park. Troops not required for guard or construction duties were-sent out to cut timber, gather brush, for the fascines and gabions used in the siege works.

Once his investment was complete the attacker bad to consider where to begin his approaches to the fortress. Usually he chose a conveniently located area not far from his base carp. Generally he would avoid flooded, marshy or rocky ground that would make construction very difficult. Often he would choose some weak area in the fort's defenses as a suitable place to attack sometimes he might begin approaching from several directions if he had sufficient forces to do so.

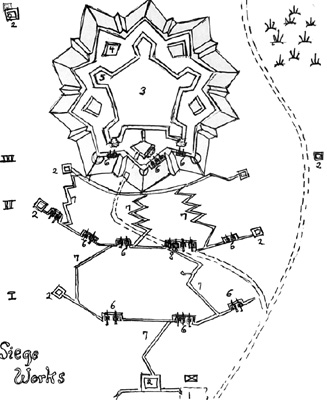

Siege Works

Siege Works

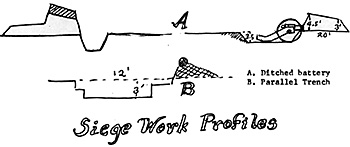

I. First parallel: trench 12 feet wide, 3 feet deep, parapet 4 feet high.

II. Second parallel

III. Third parallel

1. Artillery Park and guard

2. Redoubts

3. Fortress

4. Ravelin

5. Bastion

6. batteries

7. Saps

8. Royal or Guard battery.

Defender

The defender of the fortress might respond to the opening of a second parallel with a sortie or sally Intended to kill as many of enemy workers as possible, to delay and disrupt operations and to destroy some of the enemy guns before they could be brought into action. runs would be spiked, carriages burned. The enemy would usually withdraw quickly before the attacker could bring up his reserves. Such a sortie could of course be launched at any time, but If the enemy were still far from the work the risk of being cut off was greater.

Next the attacker right begin new saps from his second parallel, or he might begin a mine from this position. He could then extend his shaft under some part of the enemy's work and explode a charge of powder there. Usually, however, the sappers simply dug toward the fort in the usual way.

The third parallel was dug at the foot of the fortress's counterscarp. Although the enemy guns had usually all been dismounted by this time the final preparations were quite risky thanks to the dangers of ordinary musketry, wall pieces, tossed shells and grenades. Taking the counterscarp was usually very slow and costly. However, sooner or later the sappers dug up the counterscarp, often at the salient angles and erected their batteries on the counterscarp.

Naturally, if the fort had been surrounded with outworks which guardad the main fortress these often had to be taken first. Afterwards a bastion was usually attacked. If the fortress commander were any kind of gentleman he would surrender once you breached the scarn of his main work. Otherwise you needed a storming party and the events that followed could be quite messy. A defender might try to close the breach with some obstruction, such as a cheval-de-frise, or he might retreat to an interior retrenchment or some fortified inner structure (as a citadel or keen). It was only a question of time.

If a fort had many outworks, was weakly garrisoned and the rain work did not command the surrounding country, then the attacker could use the accelerated siege techniques. In this case storming parties seized the outworks and the trenches etc., were extended backward to form a reserve position, in case a counterattack drove the besieger from the outworks.

About six hundred yards from the fortress and out of effective grape range, the attacker constructed a series of batteries which he then linked together, with a trench so as to form the first parallel. Sometimes one battery was larger than the rest and this was termed the royal or grand battery. A force of about a hundred and twenty to's hundred and forty men could, according to Vauban, construct a battery for four guns in a single night's time.

Such batteries resembled other field works in

that they consisted of revetted earthen parapets pierced by gun embrasures at

Intervals. Sometimes, however, there were no ditches; usually batteries were often at

the rear. During the nineteenth Century a bank-protected road was sometimes

constructed in lieu of a trench, for a first parallel.

Such batteries resembled other field works in

that they consisted of revetted earthen parapets pierced by gun embrasures at

Intervals. Sometimes, however, there were no ditches; usually batteries were often at

the rear. During the nineteenth Century a bank-protected road was sometimes

constructed in lieu of a trench, for a first parallel.

Next the attacker began pushing saps, as these trenches were called, toward the fortress.3 At the head of each sap a detachment of six sappers and two infantrymen dug ever nearer the fortress, pushing a large brush filled gabion called a sap roller in front of them for protection. They zigged and zagged as they advanced so the defenders could not rake their trench with fire. When not harrassed that way they could gain up to about a hundred and forty yards in a twenty four hour period.

About midway to the fortress they began to open a trench on either side of the sap. Once darkness fell new batteries were erected along the line of this second parallel and the guns were brought forward to the new position. Now that they were closer the cannoniers could possibly dismount many of the guns or at least drive the gunners from their pieces. Normally it would not be possible to breach the walls of a well-constructed fortress since they would be masked by the glacis.

However, if the attacker were besieging a seacoast fort not designed to resist land attack, the defenders would be in immediate danger. The attackers' guns would not have serious trouble beginning. a breach at this distance, even in the Eighteenth Century. In fact, the besieger could have begun his breach at three times this range with the ponderous columbied smoothbores and rifled cannon of the 1860's. 4

A siege or two could be worked into almost every European campaign game since the border country of kingdoms such as France were studded with fortification of one sort or another at almost any period you might name. Invasion could be a tricky business while fortresses held out, since the garrisons might sever supply lines or cut off retreat. Also, the well stocked magazines of the fortresses could assist the invader greatly.

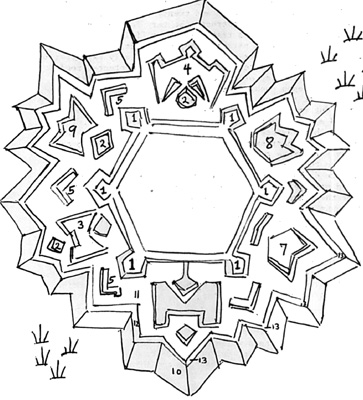

Fortress of the Mad Engineer

Fortress of the Mad Engineer

Showing Outworks

-

1. Full bastions

2. Ravelins

3. Hornworks

4. Crownwork

5. Counterguards

6. Tenaille, The

7. Simple tenaille

8. Double tenaille

9. Bonnet de pretre

10. Glacis

11. Ditch

12. Covered Way

13. Salient places of arms

14. Re-entering places of arms

Back to The Armchair General Vol. 2 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to The Armchair General List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1970 by Pat Condray

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com