The Roman eagle was the legionary standard.

However, this was not always true. During the

days of the Republic when the Roman armies

smashed the Carthaginians, there seemed to be

five standards in each legion. Pliny, who had

access to old Republican texts which have long

since perished, recorded that the original

standards were the eagle, wolf, minotaur, horse,

and boar.

The Roman eagle was the legionary standard.

However, this was not always true. During the

days of the Republic when the Roman armies

smashed the Carthaginians, there seemed to be

five standards in each legion. Pliny, who had

access to old Republican texts which have long

since perished, recorded that the original

standards were the eagle, wolf, minotaur, horse,

and boar.

Marius seems to have fixed onthe eagle as most fitting for the Roman state and made it the sole legionary standard. Thereafter, Roman armies spread the eagle through the known world and made such a deep impression, that, centuries later, empires and republics alike would claim that bird for their own.

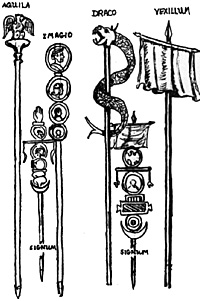

The Roman eagle (aquila) was generally wrought of bronze or silver in Republican or gold in Imperial times. Usually, it would have its wings spread wide, sometimes with a thunderbolt in its beak. At other times, it might have a corona as a decoration conferred on the legion encircling its wings, Below it, there might or might not be, a vexillium or little banner decorated by the embroidered name and number of the legion. The eagle was, of course, mounted on a tall staff.

The Romans, unlike their later imitators, regarded the eagle as more than a mere standard. The eagle was in fact a religious symbol. In its strictesy sense, it was deus legionis or numen legionis, the god or divine spirit of the legion. In case of mutiny or disorder, a commander who could reach the sanctuary where the eagle was kept was safe. The soldiers' bank was also kept in a strong room there, so that any robber would add sacrilege to the crime of theft. For this reason too, generals always had the eagle carried in the first ranks and stationed at the place of greatest danger. The primus pilum, or Roman version of the sergeant major, had charge of the eagle, but the Aquilifer did the actual carrying. Sometimes a standard bearer would heave his eagle into the ranks of the foe, well knowing the men were bound to follow.

Since the eagle was both a standard and a sacred image, it was an extreme disgrace to allow any enemy to capture it. Pride and superstition combined to make the Roman determined to keep his eagle or regain it at all costs. A legion that lost its eagle wasn't. The Roman government itself, for that matter, would go to great lengths to recover lost eagles by war or diplomacy.

Each maniple also had its own standard (signum) which was like the eagle, sacred, but to a lesser Extent. The standard consisted of a lance with a point at the bottom so that it could be stuck into the ground. The shaft was plated with silver and from a cross piece at the top, silver ivy leaves hung by purple ribbons. Sometimes a small flag fluttered below the cross-bar, while in other cases an open hand (manus), a symbol of fidelity, very appropriate for legions bearing the title "Pia fidelis" crowned the shaft. This was also a sort of pun, since the name maniple (manipulus) means "handful" in Latin. The main ornaments, however, consisted of a series of saucer and bowl shaped discs that seem to have been unit wards. Below these paternae was the animal symbol of the legion, a half moon to avert ill luck, and some ornamental tassels.

The legionary animal symbols may be astrological. For example, legions raised by Julius Caesar have the bull on the standards, evidently because the bull is the sign of the month sacred to Venus, mythologicl ancesters of the Julian house. Legions raised by Augustus carry the Capricorn sign under which he was born. Similarly, Lepidus (the triumvir) may have used the lion, and Domitian the ram, since the Aries is in the month sacred to Minerva, his patroness. The twins of the standards of the II Italica and the archer on those of the II Parthica may be explained in the same way. There were, however, exceptions to the rule, VI Alandae seems to have been the elephant in order to commemorate its brave stand against King Juba's elephants at Thapsus (46 B.C.), while Pegasus and the boar do not seem to have had astrological meanings.

According to Vegetius, the draco or dragon was used as a cohort standard. Ammianus Marcellinus also mentions it. The Romans evidently adopted the dragon sometime after the reign of Trajan. It seems to have originated in China and reached the west by way of Persia. Apparently the Roman army carried it to Britain where it became associated with the legendary Arthur and thus finally became the symbol of Wales. The Roman dragon, however, was a sort of wind sack affair: "The dragons were woven out of purple thread and bound to the golden and jewelled tops of spears, with wide mouths open to the breeze and hence hissing as if roused by anger, and leaving their tails winding in the wind." The original oriental idea seems to have been that archers could look at their standard to see which way the wind was blowing. However, this use seems to have had but little importance to the Romans.

Besides the standards that were traditionally associated with different sized legionary units there were, during the Empire, the images of the Emperor and his family. This type of standard consisted of a series of medallions fastened to a staff. Usually the largest one, at the top, would have a portrait of the reigning emperor, the second his wife or other member of his family, and so forth. The imperial images were also considered sacred, but were usually torn from their staffs during rebellions. Of course the emperor, in his own person, was often venerated as a god especially in the provinces, so it was only natural that his images and statues would acquire a little of his own divinity.

The legionary cavalry, the veterans and small legionary detachments used the vexillia for their standards. The vexillium consisted of a little flag that hung from a transverse cross bar. Sometimes the staff was also capped with an image, such as that of victory.

Not until after the Empire became Christian did tne ordinary unit standards began to lose the awe they held for the common solder. However, the government then introduced the labrum with its Chi-Rho monogram, so that the religious element was not lost. That, however, is another story.

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

1. H. Stuart Jones. Companion To Roman History.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912.

2. Amedee Forestier. The Roman Soldier. London:

A & C Black, 1928.

3. Ammianus Marcellinus. Rerum Gestarum, with

trans. by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge,

Miass.: Harvard University Press, 1956.

4. C. Cornelius Tacitus. Opera Qlload Extant,

Lipsiae: Caroli Tauchnitii, 1846

5. C. Cornelius Tacitus. The Complete Works of

Tacitus, tr. John Church and Wm. Brodribb, The Modern

Library. New York. Random. House, 1942.

Back to The Armchair General Vol. 1 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to The Armchair General List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1968 by Pat Condray

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com