In the 19th and early 20th centuries America's security rested

on a strategic triad of capabilities-the Navy, the coastal defenses, and

the mobile army. [49]

Since both ORANGE and BLACK were primarily naval plans,

American military preparations at the beginning of this century revolved

around calculations of naval strength.

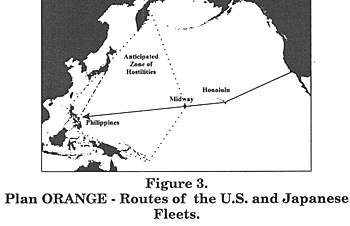

Figure 3: Plan ORANGE - Routes of the U.S. and Japanese Fleets.

Naval planners believed that the Japanese would not be able

to mount a challenge to the west coast as long as bases in Samoa,

Hawaii, and Alaska remained in American hands, but the risk to the

Philippines was much greater. The transit time for the U.S. fleet to get to

the Philippines was estimated at 68 days (or over 100 days if the

Panama Canal were neutralized), as opposed to the 8 days it would

take the Japanese to cruise from Japan. This meant that the Army would

have to defend the Philippines on its own for at least 60 days, an unlikely

prospect without external reinforcement and support.

[50]

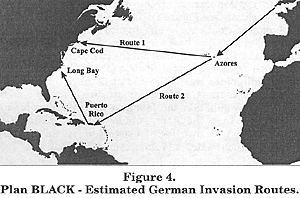

Figure 4.: Plan BLACK - Estimated German Invasion

Routes.

Like the Germans,

American naval planners recognized the importance of Caribbean

coaling stations, especially after it became clear that Anglo-German

animosity made an attack from Canada unlikely. It was here that the

Navy intended to defeat the German fleet. While the image of a

Trafalgar-like battle between the U.S. and German navies off the coast

of Puerto Rico may seem far-fetched today, it was central to U.S.

planning in the years leading up to 1917.

[51]

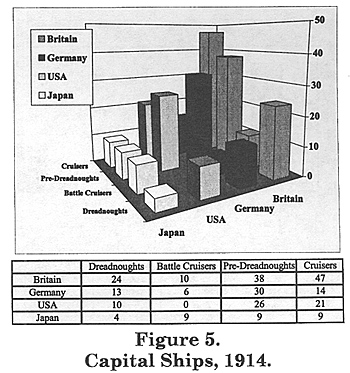

When these assessments were written, the U.S. fleet was

ranked third in the world, behind that of Britain and Germany, and

ahead of France and Japan [52] (see Figure

5).

Further, the rates of naval growth were uneven. In the years 1905 to

1914, from the Russo Japanese War to the First World War, Japan had

increased naval spending eleven-fold, German naval spending had

tripled, while American naval spending had only doubled.

[53]

This implied that the first priority for U.S. readiness was the

building of warships.

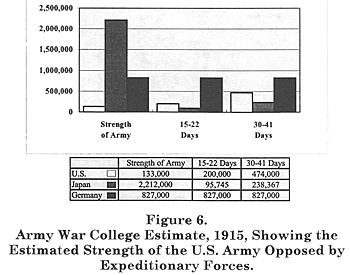

Regarding the preparedness of the American "mobile army,"

since GREEN was principally intended to counter foreign intervention,

and since both ORANGE and BLACK envisioned a war against a

hostile expeditionary force landed on American territory, calculations of required

means were all based on an estimate of the capability of potential enemy nations to transport troops by sea. By way of illustration, Figure 6, compiled from a 1915 U.S. Army War College study, shows, at left, the total peacetime strength of the armies of the United States, Japan and Germany.

In the center, a similar comparison shows the respective strength the three armies could generate after 15 to 22 days of war in the United States, the U.S. Army showing the effects of mobilization, and the Japanese and German armies showing the estimated size of expeditionary

forces transported by ship. The far right comparison shows the situation after 30 to 41 days of war. [54]

Figure 6.

Army War College Estimate, 1915, Showing the

Estimated Strength of the U.S. Army Opposed by

Expeditionary Forces.

Of course, the authorized strength of the Army at that time was

only 100,000 and, furthermore, the so-called "mobile" army was spread

thin. The shortage of Army troops was aggravated by their mal-

deployment in over 49 obsolete, Indian War vintage posts in 24 states.

[56]

This dispersion made it impossible for the Regular Army to

convert itself into a modem European-style structure, and

so while the division was recognized as the maneuver unit of

the future at war's beginning the U.S. Army had no

divisions. [57] By one

estimate, only 28,692 "mobile" troops were located within the

continental limits of the United States." [58]

The third element of the nation's defense was the coast artillery.

In the decade following the Civil War, America's coastal defenses were

perhaps the single most neglected aspect of national defense. Then the

1879-81 war between Chile and a coalition of Bolivia and Peru

rekindled interest in coastal defense. By the end of 1879, the

modernized Chilean fleet had gained control of the sea, and in joint

operations, in January 1881, a Chilean army force captured Lima,

forcing Bolivia and Peru to cede mineral-rich provinces on the Pacific

Ocean. [59]

This war, called the War of the Pacific, was the first true naval

conflict fought between ironclad fleets, and Peru's defeat suggested how

inadequate American coastal defenses had become since the end of the Civil War.

[60]

Highlighting this unpreparedness, the New York Times in 1882

reported that for the previous decade 80 percent of the Army's budget

and 73 percent of its personnel had been employed against the Indians

on the frontier, [61] leaving little

for coastal defense. The coastal defense guns available consisted

primarily of iron, muzzle-loaded pieces of Civil War vintage, inadequate

for defense against the modern naval ordnance being developed in the

1880s.

In 1885, to remedy these deficiencies, the War Department

convened the Joint Army-Navy Board on Fortifications and Other

Defenses, or Endicott Board, named for the Secretary of War who

served as its chairman. The report of this board, some 391 pages,

shaped the development of American coastal ordnance for the next 30

years.

The Endicott board analyzed coastal defense requirements by

studying the characteristics of modern warships such as displacement,

draft, and armament. [62]

Since warships which could not approach closer than 8,000 to

10,000 yards from shore could not reach land with their guns, the

design of harbor defenses depended on the depth of the harbor. [63] For example, the harbor at San

Francisco would admit deep draft vessels, but New Bedford's shallows

would only admit lighter vessels. Therefore, a shallow draft harbor like

New Bedford had no need for any heavy guns.

This type of analysis, updated with the appearance of each new

class of warship and naval ordnance, governed the strategy, tactics, and

acquisition policies of the coast artillery up to the First World War. The

basic infrastructure was in place by 1903, consisting of 70 forts in 28

locations, mounting 79 8-inch guns, 110 10-inch guns, 87 12-inch guns,

and 192 12-inch mortars [64]

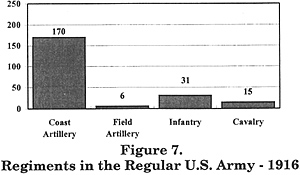

(see Figure 7).

Gunnery increased until by 1913 100 percent hits could

be scored against moving targets with a 12-inch gun at 7-9,000 yards,

and 50 percent hits on battleship-sized targets at ranges up to 15,000

yards, which was considered sufficient to deter any naval attack. The

U.S. Army led the world in the technology and tactics of coast artillery,

and if this superiority was achieved at the expense of the mobile army, the country

nonetheless felt secure. [65]

ORANGE was dominated by the logistical challenges of

sustaining American forces over long sea lines of communication (see

Figure 3).

ORANGE was dominated by the logistical challenges of

sustaining American forces over long sea lines of communication (see

Figure 3).

These relative advantages and disadvantages were reversed in

Plan BLACK (see Figure 4).

These relative advantages and disadvantages were reversed in

Plan BLACK (see Figure 4).

Figure 5. Capital Ships, 1914.

Figure 5. Capital Ships, 1914.

This line of analysis led even the most alarmist of commentators to call for levels of preparedness which fell far short of the actual First World War requirement. [55]

This line of analysis led even the most alarmist of commentators to call for levels of preparedness which fell far short of the actual First World War requirement. [55]

Figure 7: Regiments in the Regular U.S. Army 1916.

Figure 7: Regiments in the Regular U.S. Army 1916.

Back to Table of Contents Joint U.S. Army-Navy War Planning WWI

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com