In April 1904, in response to a recommendation made by

Army Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Adna R. Chaffee, Secretary of

War William Howard Taft directed the Joint Army Navy Planning

Board to:

agree upon a series of practical problems (taking them in the

order of their assumed importance) which involve cooperation

of the services, and for the execution of which in time of

emergency the two staffs will be responsible.

[41]

The Joint Board's solutions to these "practical problems" would

become war plans signed by the two service secretaries. This was the

first joint deliberate planning system in American history.

Admiral Dewey directed the chiefs of the: two war colleges,

Admiral Henry C. Taylor and General Tasker H. Bliss, to submit

recommendations on how best to get the study underway. 42 Bliss

submitted a 21-page paper, which shaped American war plans for the

next 30 years. He assumed that the enforcement of the Monroe

Doctrine, which he pointed out at the time of the War with Spain was

the "only" American foreign policy, would be the most probable cause

of America's future wars. Significantly, Bliss reasoned that the

acquisition of the Philippines expanded the Monroe Doctrine beyond

the American hemisphere. He concluded that the major European

powers would not likely attack the United States itself because

diversion of military resources would weaken them in the face of

continental rivalries; and that the real purpose of any violation of the

Monroe Doctrine would be to seize American possessions in our

hemisphere or in the Philippines.

[43]

Accordingly, Bliss's paper recommended that the two services

study the following problems in this order:

2. U.S. at war against two continental European powers [one

of which was sure to be Germany]

3. U.S. at war against a coalition of Britain and Canada; and,

4. U.S. intervention into Mexico "with another foreign

complication" [presumably a European power collecting Mexican debt]. The most virulent of all the potential enemies analyzed by the

Joint Board was Germany. Accordingly, in 1913, these studies led to

the formal plan BLACK, for war between the United States and

Germany.

In 1905, the Russo-Japanese War added another country to

the list of potential enemies of the United States--Japan. Plans for the

defense of the Philippines had previously assumed a European enemy.

[45]

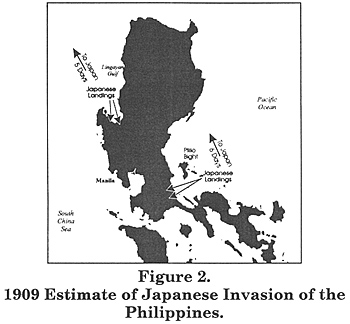

Figure 2: 1909 Estimate of Japanese Invasion of the

Philippines.

These were no mere academic exercises. Diederichs' Japanese war planning

counterpart was an Army officer named Giichi Tanaka, who in the 1906

draft of the Imperial Defense Policy included plans for war against the

United States in the Philippines. [47]

The problem of war with Japan was more difficult than war with

Germany because the distance over which the Navy would have to

project the fleet. In 1914, after 8 years of study, during which the United

States provided for its Pacific interests by signing a number of treaties

(Taft-Katsura, Root-Takahira, and the Lansing-Ishii treaties [48] ), the first edition of War Plan ORANGE for

war with Japan emerged. Making matters worse, in 1902 Japan had

signed an alliance with Britain, which meant that a war with Japan might

involve the United States in a war with Britain as well. The United

States would plan for war with Britain (Warplan RED) until 1921, the

year when the Anglo-Japanese treaty was allowed to lapse.

In 1910, a third source of potential danger emerged in the

American hemisphere. At the beginning of the century the Mexican

government was in the hands of the dictator Porfirio Diaz, who ran

Mexican affairs with an iron fist. Under his rule, however, the Mexican

economy improved, railroads were built, mines and oil wells developed,

and industry expanded. When he was overthrown as a result of the

Revolution of 1910, Mexico was thrown into a period of instability and

violence.

The violence in Mexico was in itself a peril to American

interests, but the real danger of all the revolutionary unrest in the

American hemisphere, of which Mexico was the prime example, was

that hostile powers would emulate Louis Napoleon and exploit

instability for the sake of advancing their own ambitions in the Americas.

German and Japanese advisors were already in Mexico, either in covert

or officially acknowledged status, Consequently, the measures which

were taken to provide security against a threat from Mexico, and which

eventually would be codified into Plan GREEN, were oriented as much

against the Germans and Japanese as against any indigenous Mexican

threat.

Thus, when hostilities broke out in Europe in 1914, the United

States had already contemplated the possibility of war, and had

developed plans for the employment of its military forces for the defense

of its territory and the enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine, territorially

expanded to encompass its new Pacific holdings. It remained an open

question, however, as to whether the country possessed the means to

achieve these objectives.

1. U.S. intervention in a South American country to assist the

government in ousting a foreign power supporting insurgents;

Beginning in 1906, particularly at the Naval War College, Japan

became the chief adversary for all war planning and war games

[46] (see Figure 2).

Beginning in 1906, particularly at the Naval War College, Japan

became the chief adversary for all war planning and war games

[46] (see Figure 2).

Back to Table of Contents Joint U.S. Army-Navy War Planning WWI

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com