It would be incorrect to say, of course, that no Americans were

interested in military developments in the post-Civil War years. During

the Grant administration, largely at the initiative of the Army's

Commanding General, William T. Sherman, American officers began a

program of visits to Europe. Few of these officers went there with an

open, inquisitive mind: their Civil War experience had produced a

profound complacency. Typical was the report of General Phil Sheridan,

who toured with the Prussian Field Marshall Moltke's headquarters

during the Franco-Prussian War and reported back to President Grant

that "there is nothing to be learned here professionally."

[9]

But in 1875, Sherman sent a much more astute observer: a

West Point instructor, graduate of the class of 1861, and hero of the

battle of Spottsylvania, named Emory Upton.

The orders Secretary of War Belknap sent to Upton must have

seemed fantastic to the young veteran. He was to travel from West Point

to San Francisco, and from there around the world to survey the world's

armies. His report, completed in 1877, is a detailed assessment of the

armies of Japan, China, India, Persia, Italy, Russia, Austria, Germany,

France, and England. [10]

Upton concluded with a number of recommendations which

"we should adopt as indispensable to the vigorous successful, and

humane prosecution of our future wars."

[11]

These initiatives included universal military service, a strong regular

army, a modern reserve system in lieu of the volunteer system of the

Civil War, a "War Academy" to teach officers the art of war, and a

general staff. [12]

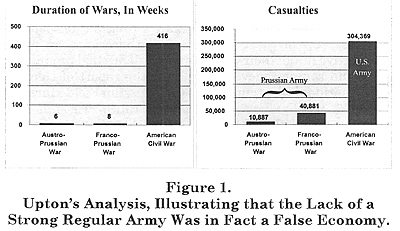

Upton based his conclusions on an analysis of cost, arguing that

an efficient military establishment in peacetime, with trained armies and

competent staffs, will reduce the wartime need for expensive

mobilization and keep casualties to a minimum.

[13]

Upton based much of his analysis on his analysis of the Wars of

German Unification (Figure 1).

In Upton's words: Twenty thousand regular troops at Bull Run would have

routed the insurgents, settled the question of military resistance, and

relieved us from the pain and suspense of four years of war.

[14]

Unfortunately, these initiatives were at variance with American

military tradition. Upton conceded that:

recognizing, in the fullest degree, that our present geographical

isolation happily relieves us from the necessity of maintaining a large

standing army, I have sought to present the best system to meet the

demands of judicious economy in peace, and to avert unnecessary

extravagance, disaster, and bloodshed in time of war. [15]

Sherman's comment on Upton's report, penciled on the cover, was

that his ideas were sound, but:

I doubt if you will convince the powers that be ... The time may

not be now, but will come when these [conclusions] will be

appreciated ....[16]

Significantly, most of Upton's arguments were based upon his

analysis of the Prussian victories over the Austrians and the French, but

he also warned that:

Japan is no longer contented with progress at home [and] is destined to

play an important part in the history of the world.

[17]

Upton was transferred to the Presidio of San Francisco, where he

developed what was probably a brain tumor. Tortured by the pain, he

took his own life in 1881. The tragedy of Upton's death was that he

believed that his life had been in vain and that his life's work would go

forever unread.

During his life, Upton corresponded with other likeminded

military reformers, among whom was Commodore Stephen B. Luce,

USN. In the Civil War, Luce had commanded a Federal monitor, a part

of a fleet trying to reduce the harbor defenses of Charleston. This was

one of the most expensive and frustrating naval operations of the Civil

War, because the Charleston defenses were wellconstructed, and even

when they were seriously damaged they were still strong enough to keep

the Union navy at bay. When Sherman's army later took Charleston with

ease from the landward side, Luce began to question the adequacy of

the education of U.S. naval officers. Until that time naval officers learned

little more than seamanship and gunnery, and nothing about naval

strategy. As Luce put it, a naval officer should "not only know how to

fight his own ship ... he should have some idea of the principles of

strategy." [18]

Luce's ideas were in keeping with prevailing American opinion

about commerce and the government's responsibility to protect

commerce, and unlike Upton, Luce found a supportive audience. He

convinced the Navy Department to institute the Naval War College, in

Newport RI, with himself installed as its first president. Luce then set

out, to find "that master mind who will lay the foundations of [naval]

science, and do for it what Jomini has done for the military science."

[19]

Luce found his man in Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, who in

1890, published one of the most influential books of its time, The

Influence of Sea Power upon History. Mahan argued that to

realize its true greatness, the United States would have to change its

continental orientation in favor of a global, maritime outlook. To do this

with an acceptable degree of security, the navy would have to transform

itself from a coastal defense force, augmented by commerce raiders,

into an ocean-going force built around a fleet of capital ships. The size

and capabilities of the fleet should be decided based upon the Royal

Navy, the world's premier navy. These analyses at the Naval War

College were the precursors of American peacetime war planning.

Figure 1: Upton's Analysis, Illustrating that the Lack of a Strong Regular Army Was in Fact a False Economy.

Figure 1: Upton's Analysis, Illustrating that the Lack of a Strong Regular Army Was in Fact a False Economy.

Back to Table of Contents Joint U.S. Army-Navy War Planning WWI

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com