With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, the diminished Soviet threat, a potential disarmament free-fall, defense budget cuts, base closures, and weapons system cancellations, it has become nearly impossible to make sense out of what is going on. Are we still safe and secure, or will our security be at greater risk in the future? I think I have found a simple way to reassure you that we will remain "safe and sound."

First the facts. The U.S. Army is the seventh largest standing army in the world. Accounting for announced military reduction plans, we will soon be the eleventh largest. If all nations mobilized their reserve forces, we would be the seventeenth largest army in the world.

[5]

Should the fact that the North Korean Army is bigger than ours matter at all? My answer is no. The reason I am comfortable with not being "number one" is that we have attained military sufficiency.

Traditionally, the military rule of thumb for the attacker to succeed against a defender has been 3:1, similar in number (but not in circumstance) to "Operation Just Cause" in Panama. If a nation can mount an attack force with 3:1 or more numbers of troops and weapon systems, it can "overwhelm" enemy defenses. That's an assumption, not a fact, but for simplicity let's use it.

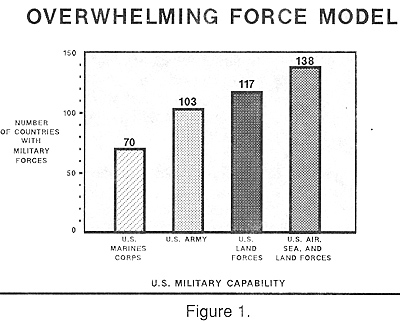

The overwhelming force model (3:1) determines that we cannot be overwhelmed by anybody. The model indicates that not even the forces of a Sino-Soviet Pact can overwhelm us today.

But will this be true after we reduce our forces? What if we use this 3:1 model in reverse? If Country X threatened U.S. interests or decided to attack U.S. property or citizens abroad, how would we respond? Would we retaliate with certainty of victory? No one can definitively answer those questions since so many important factors are involved. However, we can use the overwhelming force model as a guide to determine if we could defeat a potential enemy.

A theoretical, operational art is applied in this model which is not visible. With both superpowers seeking military sufficiency at lower levels of forces and in a more defensive,

rather than offensive, posture (defensive defense), warning and reaction time of potential surprise attack has been dramatically increased. Time, which has always been an essential factor in troop mobilization planning, is becoming less relevant and will certainly diminish in importance after the Negotiations on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) and a U.S. total force withdrawal (an assumption made earlier) are concluded.

In our scenario, Country X threatened us and decided to attack U.S. property or citizens abroad. Our military strategy would simply be to punish Country X. Under a National Security Strategy of "Selective Engagement," we would most likely react by attacking the facilities of our new enemy by air. If this action did not bring him to the negotiating table, my logic says that we would escalate the number and severity of air attacks and sink his navy. Air attack escalation would continue as a regional, operational art, starting with fighters, fighter bombers, and strategic bombers until we had destroyed his infrastructure, troop and equipment concentrations, and will to fight. If none of the above actions influenced his national will to fight, we would send in land combat forces to seize and

secure his territory, defeat his army, and establish a legitimate government. At our present strength levels, we can accomplish these feats but not without great cost and sacrifice. Is this concept credible? Perhaps.

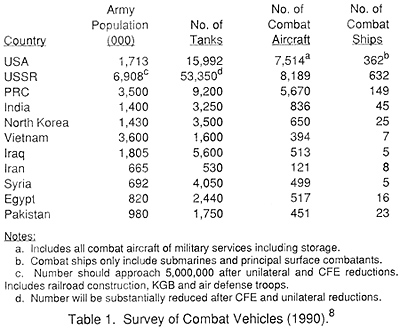

Of the 141 militaries in the world, only the United States and the Soviet Union have achieved a balance among military capabilities to win on the sea, in the air, or on the ground. The other 139 nations have opted to structure their militaries in predominantly land forces. Of those 23 nations which we cannot overwhelm by land power alone (North Korea for example with its 1,430,000-man mobilized army), only China and the Soviet Union have 5,000 or more combat aircraft. We have nearly 7,500 combat aircraft (North Korea has 650 combat aircraft). The numbers of U.S. ships and aircraft indicate that U.S. sea and air power can overwhelm virtually all nations at a 9 or 10 or more to 1 ratio, except China and the Soviet Union.

[7]

More credible is the notional aspect of this concept-that our military strength enables us to assert our will on potential aggressors, to deter them or prevent them from intimidating us, our citizens living or travelling abroad, and our free world friends and allies.

In determining how large reductions in our armed forces should be, we may consider numbers that continue to ensure that a Sino-Soviet Pact cannot overwhelm us and that powerful nations, which we barely can overwhelm today, don't attain the numbers which propel them forward into the "stalemate" category along with the Soviets and Chinese.

Although the purpose of this model is to reassure you that we have attained military sufficiency, the model can also be used to properly "size" the army of tomorrow. Given our assumption that the CFE will be concluded (perhaps this year) and that all 200,000 U.S. soldiers stationed in Europe will be returned in the next few years, it is noteworthy to say that nearly 100 percent of these forces will be eliminated from the active Army. When one adds the announced reductions of units located in the United States, a total of 250,000 or one third of the Army will be eliminated.

This leaves an active Army of 500,000. This number may be significant. When the Army numbered 781,000 soldiers, an odd number, critics demanded

to know what was in it. Such outside criticism, in addition to inside Army debates over what this new Army should consist of, e.g., more artillery, fewer tanks, less engineers, more infantry, etc., left the Army focusing inward in its Total Army Analysis (TAA) process at a time when we should have been focused outward, finding the logical patterns of the future. In any case, 500,000 or half a million is the number which makes logical sense (since it's smaller) and a round, understandable number which staves off obvious explanation of its internal composition. It is a politically viable number, which "sticks on the wall," (similar to the 600-ship Navy), but is it the right number for the Army? Will we still have the appropriate balance among the services to remain as secure as we are today?

From this survey of selected data we can theoretically determine that a reduction to an army of 500,000 will not change our security position in the model. We are still stalemated by the USSR and China (PRC), and although Vietnam has a much bigger land force, that country cannot overwhelm us in the model. If we reduce our active and reserve forces by 750,000 to 1,200,000, we risk being overwhelmed by the USSR, China, Vietnam or a Sino-Soviet Pact and thus, greatly decrease U.S. security. A Total Army reduction of 750,000 is too much. When U.S. Marines are added to the new U.S. Total Army figure (1,200,000 + 282,100 = 1,482,100), only the Soviet Union could overwhelm us in the model, which still increases risk and reduces security.

A total U.S. land force reduction of 600,000 (add Marines, subtract 350,000 more than starting figure which includes a 250,000-man reduction) is as low as we dare go in reducing land forces, unless the Soviets reduce lower than an estimated 5,000,000-man force. Simple math may not be the right answer to the question of "how low can we go," but it is a starting point. My force mix solution of the model's 600,000 reduction intuitively would include a 250,000 cut in the Active Army, a 300,000 cut in ready reserves (Army Reserve and Army National Guard), and a 50,000 cut in total Marine forces (active and reserves). The logic for this vision will be explained when we discuss the Comparative Resources Model later in this report.

At this point, however, the reader should look closely at the resources chosen in Table 1, even though we will be analyzing the data later on. Using our 3:1 model criterion, the air and sea data, after we discount the United States, USSR and PRC, should intuitively lead you to at least think about naval and air power arms control in some near-term timeframe.

Please remember that this is a highly generalized model, intended only to represent reality in terms of illustrative military sufficiency in the most basic manner. The model certainly is too simplistic for actual use in structuring detailed military capabilities, but it serves as a good guideline or framework for reassuring you that we will remain militarily strong in the future. Conceptually it allows us to preview and analyze force reductions before they are made in the turbulent decade ahead.

Now let's turn our focus on the missions this smaller military force will perform in the next 10 years. The Aversion Policy Model, next at hand, is perhaps the most interesting we shall discuss.

Figure 1 graphically depicts how we compare or are ranked at achieving overwhelming military superiority. Of the 140 other nations with military forces numbering more than 1,000, the fully mobilized (Active and Reserve) U.S. Marine Corps by itself can overwhelm 50 percent of them. The Total U.S. Army can singularly overwhelm 80 percent of these nations. The combined U.S. Marine and Army forces can overwhelm 90 percent. But there still remain 23 countries that we cannot overwhelm without adding massive air and sea power. Remembering that this is a simple model which does not include terrain, technology, ideology, nationalism, political will or religious fervor, we can theoretically overwhelm 138 of the 140 nations when air and sea power are added. A stalemate will result in facing the Soviet Union or the Peoples Republic of China, since we cannot overwhelm them, nor can either or both of them (as in a Sino-Soviet pact) overwhelm US.

[6]

Figure 1 graphically depicts how we compare or are ranked at achieving overwhelming military superiority. Of the 140 other nations with military forces numbering more than 1,000, the fully mobilized (Active and Reserve) U.S. Marine Corps by itself can overwhelm 50 percent of them. The Total U.S. Army can singularly overwhelm 80 percent of these nations. The combined U.S. Marine and Army forces can overwhelm 90 percent. But there still remain 23 countries that we cannot overwhelm without adding massive air and sea power. Remembering that this is a simple model which does not include terrain, technology, ideology, nationalism, political will or religious fervor, we can theoretically overwhelm 138 of the 140 nations when air and sea power are added. A stalemate will result in facing the Soviet Union or the Peoples Republic of China, since we cannot overwhelm them, nor can either or both of them (as in a Sino-Soviet pact) overwhelm US.

[6]

Let's now test the model using Total Army figures, which include ready reserve units. We have subtracted 250,000 from the U.S. totals in Table 1, which depicts the United States and the largest 10 military forces of the 23 nations we cannot overwhelm with land power alone.

Let's now test the model using Total Army figures, which include ready reserve units. We have subtracted 250,000 from the U.S. totals in Table 1, which depicts the United States and the largest 10 military forces of the 23 nations we cannot overwhelm with land power alone.

Back to Table of Contents Justifying the Army

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com