The key to understanding this theory is recognition that real power has shifted from military to economic and diplomatic or political might. The revolutionary events in Eastern Europe were allowed politically by Mr. Gorbachev to overcome drastic economic shortfalls in the USSR brought about by an archaic political system. Continued competition in the arms race with the West only compounded Soviet economic problems. The United States as well has experienced economic woes because of superpower military competition, costing 2830 cents of every tax dollar collected in 1986.

[25]

Although real U.S. defense growth has been negative since then, we are still spending 24 cents of every tax dollar on defense in 1990. [26]

As long as we continue to keep defense expenditure growth at less than Gross National Product growth (and thus below tax revenue growth), the cents of every dollar spent on defense will continue to decline.

[27]

That's the good news. The bad news is that to remain economically competitive in the world, we may reduce defense expenditure to levels which may erode today's U.S. military sufficiency. The obvious answer to our deficit and economic woes is twofold. We must either increase our national productivity and savings, or cut government expenditure, or both. I propose both.

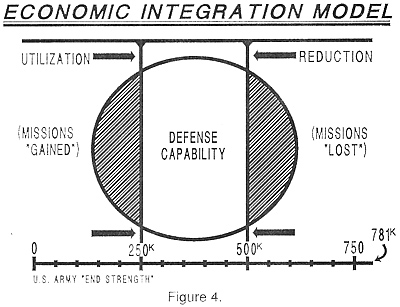

By offering force reductions and weapons cancellations, we can help American competitiveness. But we must not reduce defense expenditures below some reasonable standard of military readiness, and thus return to a "hollow Army." A concept which logically follows is one which integrates military and economic power. The Economic Integration Model (Figure 4) will help us to understand the nature of this integration.

In the model we will find a horizontal axis of reductions and utilization. What is depicted are bounds of two options: reduce forces or keep forces, but use them for national economic gain as well as defense. The horizontal axes are quantitative. If we reduce Active Army force structure to 500K, we have also reduced the amount of defensive capability (in the shaded area). This reduction was noted in our discussion in the 3:1 Model. At the utilization bound we may begin to use existing force structure to make us more economically competitive. Both vertical quantifier lines slide as an engineer slide rule does.

As we increasingly use existing soldiers for nonmilitary missions, we also will lose some portion of our defense capability, e.g., the force will not be as ready to go to war if it

does not train for war. What is left in the model is the difference between the reductions and the number of troops integrated into economic support. This difference is our ready army, one which trains for combat. Although those who work to make us more competitive also train, they are not as ready for war because war readiness is directly related to training time (a military axiom).

What do these folks do in the right side of the model? They are used in many ways. Recently the Governor of Michigan offered his Army National Guard for use in demolishing "crack houses" and dilapidated houses on sheriff sale books.

[28]

The Mayor of Detroit immediately requested that the National Guard demolish 1,500 properties in his city. Soon, on weekend training assemblies and during annual summer training, the guardsmen will be actively engaged in this worthwhile activity. In effect, the mayor and the governor will get "Two-fers" because the city's tax base will increase as new commercial structures are built on the old properties (with no current tax revenue), and the elimination of crack houses will contribute to the security of local neighborhoods. In effect, the federal government is also receiving a "two-fer" deal. It pays for soldiers it needs for national security, while it fights the drug war simultaneously. There are lots of examples of federal and state National Guard support to the drug war which accomplish the same thing, e.g., military customs inspection support, radars, helicopters, naval and air force support. Drug war support, however, is not a classical example of the integration of military and economic power because much of the support provided can be performed as military training, and thus, no reduction in readiness occurs. The use of soldiers by East Germany to replace industrial workers and coal miners as a result of the flight of those workers to the West is an example of what I am advocating.

As we reduce the force we should be looking for units which can assist the private sector with support which equates to training readiness: the emergency medical personnel, helicopter pilots, clerical and information management specialists should be retained and integrated into the civilian

world. Their training is their work and vice versa. They can easily support police work by freeing the administrative personnel slots taken in a municipal police force for more line officers. Hospitals in remote rural areas could utilize our military medevac units in cases where the communities could not afford such services. Is this irrational?

Imagine the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff asking an annual mayors' or governors' convention if the military could help them. He would be besieged with requests for support which would cover the full spectrum of military occupational specialties (MOS). There is much we can do to increase economic productivity. Quantifiable things. Excess military bases could be used for a variety of functions including prisoner overflow, drug rehabilitation centers, housing for the homeless, and education and training centers for captured illegal aliens. (We capture and return over 1,000,000 per year. Why let them go? Why not train them in our language, customs, and a skill needed as noted by shortages in our labor market?) Even the military's transportation capabilities can be utilized to move the unemployed through a training center to a programmed job somewhere. We performed these kinds of activities during the highly successful Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. The political viability for these many activities may seem low, but how does this concept compare with trying to shut down a major military installation in a powerful congressman's district? It certainly is more feasible to use military assets for domestic needs than it is to close military bases. Passing legislation needed to help America compete is surely easier than preparing environmental impact statements-anytime.

The integration of economic and military power is an evolutionary concept. As we utilize soldiers more in the drug war and in support of other domestic policies, new paradigms for use will naturally develop. The Aversion Policy Model presented earlier also addresses this utilization of military assets in support of national policies, but we only addressed five of several hundred issues which need to be put into that model. An important tenet to remember when using this Economic Integration Model is that the more we utilize existing troops to support domestic policies, the less defense we have.

Certain combat troops (in the model I dedicated 250,0000) must be isolated from integration to retain a military option for crisis resolution. The active 250,000 combat force is then backed up with 250,000 support troops. I refuse to state what this 500,000 Active Component Army consists of below the resolution provided. So should the Army Staff. It is the Army's job to construct the force. The job of the Congress is to raise the funds. Again, the estimate of 500,000 protects itself from external audit by its simplicity, but only if we keep it that way.

If I said that the 500,000 consists of 10 divisions at 15,000 each; 250,000 support troops; 50,000 special operations forces; and 50,000 miscellaneous, Congress would surely take the miscellaneous away from us. But Reserve Component strength surely will be closely scrutinized. This Army of the United States, as opposed to Active forces in the United States Army, particularly the state National Guard, has more political integration and influence with the U.S. Senate than the Regular Army. Their work in disaster relief, crowd control, rescue operations, drug war support, playground and park construction and repair, and many other domestic missions assigned or approved by state governors make these forces more difficult to direct, command and control by the Regular Army.

This evolving internal debate is consuming much of the Army's intellectual capital. How do we resource and structure the Reserve Components to balance risk encountered when we reduce the active force? The source of my proposed 600,000 reduction in the 3:1 Model is intuitive: 250,000 Active; 300,000 Reserve Component; and 50,000 Marines (either or both components). Subjective Pairwise Comparison and other analytical tools won't work. However, if we structure for the new mission gains in the Aversion Policy Model and ensure a balanced resourcing of scarce budget dollars in the Comparative Resources Model, and learn how to utilize troops to increase American economic competitiveness in the Economic Integration Model, political as well as security concerns will seek consensus in support of economic necessity. Numbers need to be used as targets for the future. Mixes of resourcing should remain balanced among the services and within Army components. All decisions will need to be flexible in our ultimate justification of the Army.

Back to Table of Contents Justifying the Army

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com