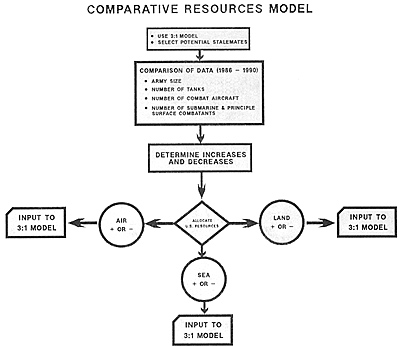

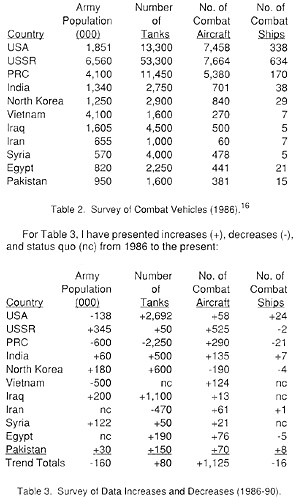

The Comparative Resources Model is shown in Figure 3. in this model we will revisit the Overwhelming Force Model (3:1 model) and the data provided in Table 1. This time we are going to compare the force data from the International Institute for Strategic Studies The Military Balance 1989-1990 with the data presented in the 1987-1988 version to analyze what happened to our 10 selected militaries from 1986 to 1990. (See Table 2 and Table 3.)

The Comparative Resources Model is shown in Figure 3. in this model we will revisit the Overwhelming Force Model (3:1 model) and the data provided in Table 1. This time we are going to compare the force data from the International Institute for Strategic Studies The Military Balance 1989-1990 with the data presented in the 1987-1988 version to analyze what happened to our 10 selected militaries from 1986 to 1990. (See Table 2 and Table 3.)

Next we will determine the increases and the decreases in each comparison category-Army size and numbers of tanks, combat aircraft, submarine and principal surface combatants. Then we will analyze the increases and decreases to discover where other nations are spending their defense dollars to find an allocation of U.S. defense dollars in the appropriate land, air and sea services which strengthens our weaknesses while maintaining our strengths.

Finally, we will input our new numbers back into the 3:1 Model to insure we have not increased risk or lost security.

A quick analysis of the non-U.S. numbers indicates that 60 percent increased the size of their armies; 70 percent ,increased the number of tanks; 90 percent increased the number of combat aircraft; and 30 percent increased the number of combat ships. The trend totals above indicate decreases in Total Army population and number of combat ships, with increases in tanks and combat aircraft. Analysis by population column indicates that USSR data in the IISS figures is suspect and that Vietnam drew down forces when retiring from Cambodia.

In the tank column, Iran lost a lot of tanks in the Iran-Iraq War while data on the PRC is suspect. In the aircraft column there does not seem to be an adequate explanation for North Korea's data. Finally, the ship column depicts reducing ships at twice the pace of those who increased their inventories (India and Pakistan).

Although analytical excursions should be run concerning the suspect data, the general trends include increased resourcing of land and air power and a significant decline in sea power resourcing. Then where should we put our money? Should we follow the trends of potential adversaries or continue balancing our resources among the three services? To begin our discussion let's return to the 3:1 Model and use Table 1.

Antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capability must be improved. The P-7 replacement for the P-3 Orion must be brought on board soon. Surface Ship Towed Array Radars must be improved in the real world, not in this model. We need a new, lighter, more lethal tank and an effective antitank weapon now for the Army. However, in resourcing the Air Force we must look at the B-2 bomber, the C-17 transport, the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) and two versions of ICBMs.

Although this resource model does not address the strategic triad or selection of Marines or the Army when addressing land power, let's make short discursive excursions to increase our understanding of the resourcing problem.

In strategic forces we need to simply determine whether SDI is going to work or not, and if it will, determine its true cost to society and its true benefit to security. Let's assume it will work at a price we are willing to pay. If such is the case, logically we should scrub the B-2 and at least one of the missiles (preferably the Midgetman because it's more expensive). If SDI won't work or will, but is just too costly, then pare down SDI to its land-based weapons research in directed energy, particle beams and lasers; give it a new name; and still cancel one missile and the B-2. This would leave sufficient funding for a reduced purchase of the ATF and the C-17 (due to reduced needs) with funds left over for other service needs.

In articulating the Marines versus the Army debate I'll start by stating that there is no debate. Although several journalists, ex-sailors, Marines, and even ex-Naval Secretaries are quite vocal concerning their support of increased budget market share for the Marine Corps and Navy in relationship to the Army's budget, there is no official debate at the highest level of military leadership, the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

There is a logical thought process for a debate which focuses on the current budgets for the Army, Navy and Air Force. The 1991 budget gives 25.7 percent to the Army, 33.7 percent to the Navy and Marine Corps, and 32.1 percent to the Air Force. [18]

All percentages have remained virtually unchanged for the past decade. When we begin to address the hard force structuring and budget questions concerning fiscal constraints and strategy development, most Pentagon observers logically view a real debate between the nation's land forces for budget supremacy, or minimally, mission selection.

Those who support the Marines for such favor cite several practical reasons for their service of choice. Some of their thoughts are [19] :

In effect these arguments speak to the actual mission of the U.S. Marine Corps as stated in Title 10, United States Code [20] :

The U.S. Army counterargument is no argument at allthe U.S. Marine Corps and the U.S. Army are complementary services, not competing services. The missions of the two land forces are different. Title 10 states that the Army's mission is [21] :

In fact all four military services are components of a larger team, not unlike the offense, defense and special teams of a football team. But for the sake of argument, I'll take issue with the Marines-that they are the service of choice for future conflict warfighting in the Third World. My debating thesis is that the U.S. Army is the service of choice for small wars because:

What both of these arguments indicate is that the military services-all of them-are complementary. It is not an "either-or" debate. The real debate is between advocates of low cost/low tech defensive strategies and high cost/high tech solutions. People or expensive things? When time was the critical element in mobilization, high cost/high tech solutions were favored because there would not be time to build expensive power projection vessels in a short-warning scenario. Now things have changed. We have plenty of time, which should favor people over things. This argument is now moot. We should seek solutions which are low cost/high tech, and that means favoring research and development which support soldiers, sailors, marines and airmen, rather than R & D which replaces them.

The Marines versus Army debate leads us logically into a mission specialization discussion. Each service is attempting to retain structure in what it does best. In doing so duplication of capabilities is inevitable. If we are truly moving to a "joint" force in accordance with the Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, in time of drastic budget reductions we will need to eliminate such duplication. We must learn how to interchange missions among the services.

The Army has conducted a Total Army Analysis (TAA) for years. During the TAA, many trade-offs are made. The TAA is a formal process to determine the force structure requirements for both Active and Reserve Components through the program years, while generating the base force which reflects the most recent doctrinal modifications. In

earlier years support forces were removed from the Active force and placed in the Reserve Component, while backfilling the resultant support force requirement with Wartime Host Nation Support (WHNS) forces. The 1982 WHNS agreement with the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) involved the creation of a German reserve force of 93,000 to perform a variety of combat service support (CSS) missions, including airfield damage repair and transportation support.

[23]

The startup and sustainment costs of this force structure ultimately was to be shared about equally by the FRG and the United States. (We should relook our funding commitment to this program in light of current budget constraints and assumptions made for the future.) This agreement, which trades capability for funding, was necessary to replace U.S. support structure which in turn was converted to combat structure. The TAA process is a personnel space-by-space process designed to increase the deterrent value of force structure without increasing capital costs.

[24]

The TAA process does consider other Army programs such as Functional Ar ea Assessment (FAA) and Mission Area Assessment (MAA), both conducted on a biannual basis. These programs seek to structure our Army with more firepower, mobility and logistical support from within existing structure and they have been successful. It is now time for the Joint Chiefs of Staff to consider establishing a Joint Service Analysis to enhance the firepower, mobility and logistical support of joint force structure, which necessitates mission trade-offs:

From lists like the above, hard questions need to be asked. Does each service need a given capability? Can a mission tradeoff benefit jointness, e.g., resolve naval on-shore stationing problems, while enhancing military effectiveness? Are customs and traditions of each force more important than the whole of U.S. defense? Such a joint program would certainly enhance internal debate among our senior leaders to fight for customs, traditions and budget market share. But through conflict resolution and trade-offs, won't we arrive at a more beneficial force structure than the Congress could design?

If we don't tackle this debate and make sound, logical decisions, Congress will do it for us based upon location of forces and industry. Because the Department of Defense in its latest base closure debacle did not insist that the services examine each others' closure offerings, we made illogical mistakes and Congress knows it. When we return forces from Europe, we aren't going to leave the equipment there. That's illogical.

Where will we store 10 divisions' worth of equipment now located in Europe? Logical storage sites are located at or near ports. Then why are we closing the Philadelphia Naval Yard? This is an illogical decision, brought about by traditional separate service mindsets, not a joint service mindset. Congress will "eat our lunch" on base closures and other issues unless we learn to trade off missions and respond with joint rationale.

Discursive excursions such as these are germane to understanding the comparative resources problem. Do we structure to offset our weaknesses or strengthen areas where we are strong? I think we might best use U.S. Competitive Strategies theory in reverse. Attacking an opponent's weakness, the current comparative strategies doctrine, does not seem as logical as it did just a year ago.

A balanced strategy, one able to respond to a wide array of policy options, while utilizing the force in peacetime for purposes which increase American productivity, is my answer. Forget competitive strategies. Trade off missions which will produce the best cost-benefit ratio. From the Overwhelming Force Model we can consider decreasing landpower forces by 600,000. We can park 4,500 airplanes and seek naval arms

control for sea service reductions. From the Aversion Policy Model we can find mission increases and decreases which are neutral in size (as one is reduced, one is increased). From the Comparative Resources Model we find that our traditional balanced approach to structuring the services is more appropriate than focusing on enemy weakness; that mobilization time has been lengthened to rationally deflate arguments for increased power projection lift capability; that defensive rather than offensive forces may offer greater utility in the next decade; and that limited resources need to be allocated to alleviate defensive weaknesses in a balanced approach (ASW, antitank, etc.). Now let's look at the last theoretical model, the Economic Integration Model.

As notes c. and d. under Table 1 state, CFE and Soviet unilateral reductions will impact greatly on the final military balances. Of the 7,574 U.S. aircraft, over 1,700 are currently in storage with hundreds more subject to the CFE negotiations. Based on a revised estimate of 7,000 combat aircraft for both the United States and the USSR after CFE agreement, less aircraft in storage, I estimate that both sides will maintain approximately 5,000 combat aircraft, if the budgets permit such, but they won't on either side. This indicates that, although the 3:1 Model would allow us to fly as few as 3,000 combat aircraft in the U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marines combined, and still achieve stalemate with the USSR and PRC, while maintaining a decisive 3:1 or more advantage over the nearest competitor, further arms control (CFE 11) would be the best way to approach air power reductions. Sea power is also "ripe" for harvest and it may be in our best interest to proceed,

even though naval arms control is certainly problematic. Any savings generated in storing submarines and principal surface combatants must be reallocated back to the Navy to redress current threats of increasingly undetectable new classes of submarines. [17]

As notes c. and d. under Table 1 state, CFE and Soviet unilateral reductions will impact greatly on the final military balances. Of the 7,574 U.S. aircraft, over 1,700 are currently in storage with hundreds more subject to the CFE negotiations. Based on a revised estimate of 7,000 combat aircraft for both the United States and the USSR after CFE agreement, less aircraft in storage, I estimate that both sides will maintain approximately 5,000 combat aircraft, if the budgets permit such, but they won't on either side. This indicates that, although the 3:1 Model would allow us to fly as few as 3,000 combat aircraft in the U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marines combined, and still achieve stalemate with the USSR and PRC, while maintaining a decisive 3:1 or more advantage over the nearest competitor, further arms control (CFE 11) would be the best way to approach air power reductions. Sea power is also "ripe" for harvest and it may be in our best interest to proceed,

even though naval arms control is certainly problematic. Any savings generated in storing submarines and principal surface combatants must be reallocated back to the Navy to redress current threats of increasingly undetectable new classes of submarines. [17]

To maintain the Marine Corps, which shall be organized, trained, and equipped to provide Fleet Marine Forces of combined arms, together with supporting air components, for service with the fleet in the seizure or defense of advanced naval bases and for the conduct of such land operations as may be essential to the prosecution of a naval campaign..."

To organize, train, equip, and provide forces for the conduct of prompt and sustained combat operations on land-specifically, forces to defeat enemy land forces and to seize, occupy, and defend land areas...

Back to Table of Contents Justifying the Army

Back to SSI List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 by US Army War College.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com