The Chinese Civil War and the revolution of 1949 was one of the most important post-war political events. Its geo-political effect was enormous, and added fuel to the already raging cold war. The 30th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution fell in 1979, and to mark the occasion an English game company released a game on this very topic.

The Chinese Civil War and the revolution of 1949 was one of the most important post-war political events. Its geo-political effect was enormous, and added fuel to the already raging cold war. The 30th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution fell in 1979, and to mark the occasion an English game company released a game on this very topic.

Called Chinese Civil War, and sub-headed 1946-1949, it appeared in Wargamer magazine 10, and the company in question was Simulation Games, the forerunner of World Wide Wargames, which was eventually shortened to the more well known 3W. Simulation Games also produced a number of boxed titles as well (I still have my copy of Desert Rats, which is an interesting treatment of the Desert war in WWII). The first edition of the classic Aces High was also initially published by Simulation Games. Chinese Civil War lists as the designer Bob Fowler, and the playtesters included Jim Hind, Chris Hunt, the Carleton University Wargaming Club in Ottawa, and also one Keith Poulter. The magazine was unavailable for review, but for those unfamiliar with the early Wargamer, it was a game bundled with what was basically a review journal, though each issue could include a brief historical piece on the featured campaign.

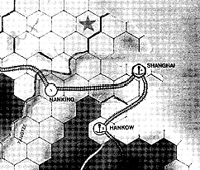

The game is strategic in focus, with the unmounted map featuring northern and eastern China, from Chengtu in the south west to Manchuria in the north east (to maintain consistency with the game components, Iíll be referring to people and places in the old style; e.g., Beijing will be referred to as Peking). The game credits list David Green in charge of graphics, and given the gameís vintage, and the fact that it was published by a third world (in terms of size, not location) game company, the map graphics are very serviceable. The mostly browns and tans may give the impression that Chinaís mostly desert, but nonetheless itís not the eyesore that some of the later 3W maps were (such as the shocker in No Trumpet No Drums).

In general the different terrain features are easy to distinguish. Hexes appear on the land portion of the map only, so the coast is dotted with partial hexes. Again, most of these are straightforward enough, though there are one or two rather tiny hexlets to be found. Terrain features include clear hexes, desert, rough, cities, fortresses, and of course the mighty Yangtze and Hwang Ho rivers. The single-sided counters are a little bland, being blue on white for the KMT and red on white for the Communists, and some are a little smudged. A nice touch is the use of Chinese characters on the counters, which help give them a certain amount of, well, character. Of the 200 counters in total, 92 represent the Communist Peoplesí Liberation Army (PLA) units, the remaining 108 representing the Kuomintang (KMT). PLA units include PLA bases, infantry, guerrilla and artillery units. The KMT have a little more variety, with infantry and cavalry plus an array of supporting units such as Communications Police (which guarded the rail net from guerilla attacks), headquarters, leaders, supply, air transport and fortress markers.

The generic-sounding KMT leaders (Chu, Yen and so on) do appear to correspond to actual KMT commanders that are named in the historical outline in the back of the rules. Sadly, there are no PLA commanders in the counter mix. Leaders such as Chu Te, the PLA commander in chief, and Lin Piao, were gifted commanders. Perhaps there was no room in the counter mix, but maybe one or two of the Ď0í value KMT leaders could have been substituted for PLA ones.

One thing which is totally absent from the design is any mention of scale, either of the map or of the counters. It is possible to make some guesses, but guesses they must remain. According to my edition of the Macquarie World Atlas, itís (very) approximately 650 km from Peking to Nanking. On the map itís 26 hexes between the two cities, which translates into roughly 26 km. So depending upon the accuracy of my measurements, each hex would seem to be roughly 20 to 30 km.

Things are slightly more complex with the counters. Given the strategic level of the game, one can probably assume that each counter approximately represents army-level formations. Itís not possible to say how many are represented by each counter, but again a little guesswork is possible. For example the historical article states that by 1949, the PLA had approximately 2,100,000 regular troops under arms. In game terms there are a total of 61 counters representing PLA regulars. This means that, assuming the maximum strength of the PLA is represented by all those 61 counters, each one could represent up to about 320,000 combatants (I make that one magnitude smaller -ed), although the real figure is probably considerably less.

The game structure is quite simple, with the KMT player going first. The phasing player firstly takes reinforcements and replacements, followed by movement and combat. The rules in places have the clarity of a mud brick, so they do need to be read very carefully. For example, the setup rules for the KMT are quite unclear, stating: ďthe KMT player then deploys all his units, including combat, leaders, headquarters and supply units...Ē

Two sentences later the rules state: ďa maximum of two +1 leaders may may be used at the start, in addition to ĎMaí (Ningsia)Ē. Given that there are three +1 leaders, what happens to the other? If one goes to the reinforcement section, one discovers that the additional leader appears on turn four. In addition, the reinforcement/replacement rules mention that level Ď0í leaders may be used to replace those who have been killed, which again seems to contradict the setup information. Indeed, thereís no indication in the set up section of the rulebook exactly which Ď0í leaders start the game. The mystery is never really revealed. The only clue is that one of the Ď0í leaders has ĎShansií printed along the side, whereas no other Ď0í leader has a province name printed on them.

My interpretation was that this Ď0í leader started the game on the map, with the others as replacements. None of the ambiguities will prevent play, but are frequent enough to cause a player to read the rules while scratching oneís head.

My interpretation was that this Ď0í leader started the game on the map, with the others as replacements. None of the ambiguities will prevent play, but are frequent enough to cause a player to read the rules while scratching oneís head.

However, an additional 2.5 pages of historical outline are also included at the back of the rules, which will give players unfamiliar with the struggle a sense of whatís going on. Though even here itís not clear where the rules end and the commentary begins. On my first read through, it was only after reading the first couple of paragraphs of the commentary that I realised that the rules were finished (though Iím sure some would argue that it says more about your reviewer than the rulebook).

However this basic system has some nice chrome which captures well the main points of the campaign. The KMT is hampered by supply and command rules which help prevent it from bringing its full weight against the PLA, though the KMT is able to deliver some powerful blows indeed. Both sides must be able to trace supply to a valid supply source to operate at full effectiveness, but in order to attack, the KMT must be within two hexes of a supply unit, which is expended when the attack is carried out. As there are only a few such units (there is also a supply unit in Ningsia, but it can only be used for that city), the attacks must be made carefully. There will be times when a KMT player will want to carry out more attacks than he is capable of, which will be a real source of frustration for the KMT player.

The other frustration for the KMT is the existence of nine war zones, to which units are initially assigned. Although units can move into different war zones, there are restrictions placed on stacking with and cooperating in combat with units from different war zones. It nicely simulates the command problems (not to mention phenomena such as endemic corruption) suffered by the KMT military.

Combat is the standard odds-based CRT with odds from 1:2 up to 6:1, with typical modifiers for terrain. Results range from attacker eliminated, to exchanges to defender eliminated. However each side, when attacking, roll on their own CRT. The PLA are more likely to cause losses to their opponents. At 4:1 or greater, the PLA can cause KMT units to surrender, to be replaced by a PLA unit. Even at 3:1, the PLA has a one in six chance of a DE result, while KMT units can only eliminate PLA units if a +1 leader accompanies the attack. PLA units may also retreat into neighbouring North Korea or Mongolia, while KMT units that do so are eliminated.

But itís not all plain sailing for the PLA. Despite their advantages they are generally, unit for unit, weaker than their KMT counterparts, and are at their most vulnerable early in the game. The PLA start with 14 bases spread across the map, the majority located in Manchuria and Honan. Each base adds one strength point to the hex the base itís in, as well as the six surrounding hexes. As well as providing added security for PLA units the bases are where PLA reinforcements and replacements enter the map. PLA units begin the game in unconventional mode, which allows them to move directly from one KMT ZOC to another, with one subtracted from the die when resolving attacks. The PLA may shift into conventional warfare as early as turn seven, and must begin conventional warfare on turn 12. Though the PLA cannot move directly between enemy ZOCís during movement, this is compensated for by removing the -1 modifier for combat, and increasing the PLA stacking limit.

Of course a civil war would be nothing without guerrilla warfare, and the PLA have at their disposal a number of guerrilla units, whose function is to attempt to block KMT rail movement. Whenever KMT units attempt rail movement through a guerrilla hex, the PLA player rolls a die, with movement blocked for the turn on a 1 to 4, the unit ineffective on a 5 or 6. The KMT have available rail police who are charged with the task of ridding the rail network of these pesky guerrillas. Each police unit represents one-half of a suppression point. To suppress guerrillas, the KMT adds up the number of police units present and consults the appropriate table. If an ĎRí result is obtained the guerrilla unit is removed.

Both sides have a number of strategic options available, though often the KMT will have to react to moves set by the PLA player. The rules encourage a concentration of strength in Manchuria, partly because more than half the PLA units that enter as reinforcements must appear to enter Manchuria. Honan is another strongly dominant city. However, the PLA can certainly choose to concentrate on smaller isolated provinces and work outwards. Certainly by midgame hopefully for the PLA they will be attacking frequently. At the beginning of the game the KMT possess 70 city points, and the PLA 14. For a PLA tactical victory the PLA must accumulate 56 cities. As most cities are worth two to four victory points the PLA must keep up constant pressure in order to garner the necessary VPís.

Chinese Civil War does not really seem to fit into the classic wargame niche. The rules are not brilliantly written, the counters are rather bland, and the topic does not really seem to have mass appeal. But lurking within lies a little gem. Both players must alternate between all out attack and desperate defence. Though the rules can tend to guide the situation towards historical paths both players have a number of strategic options open to them. Perhaps the PLA player is slightly favoured, but if there is imbalance it would be 52:48 rather than 60:40.

Itís a significant game in some ways because it shows what the early Wargamer was capable of. It was not afraid of tackling unusual topics. The previous issue featured the game Bloody Buna, which featured the first major land reversal suffered by the Japanese Imperial Army at the hands of western powers during WW2. It took place in that neglected New Guinea theatre, in a campaign in which Australian troops played a prominent part (something rarely seen at the game table). Indeed, the first issue of the Wargamer featured The Battle of the Ring which came out in the same year that SPI issued its own Tolkien game. So Chinese Civil War represents what the early Wargamer seemed to represent; the desire for innovation which at its best came close to the mark, but could be hit and miss. It was reissued by 3W in the mid-1990ís, not too long before it joined what must by now be a rather cavernous dustbin of wargaming history. It maintained the same map, but with a counter and rules update. Given the record of development with the late 3W, one might indeed be better off with the original. Be that as it may, this is a little classic that has long been neglected by the hobby, and deserves a much wider audience.

Components

200 single-sided die cut 1/2Ē counters (109 Kuomintang and 91 PLA)

1 23ľĒx34ľĒ full color paper map

1 eight-page rules folder (5 1/2 pages of rules & charts and 2 1/2 pages of historical notes)

1 issue magazine Wargamer 10.

Counter Manifest

PLA (red on white)

61 PLA Infantry

20 PLA Bases

8 Guerillas

2 Artillery

Kuomintang (blue on white)

53 Kuomintang Infantry

16 Police

12 Leaders

9 Headquarters

7 Fortresses

6 Supply Units

3 Cavalry

3 Air Transport

Collectorís Value

Boone lists low, high and average prices of 11/30/19.75 at auction and 6/60/21.80 for sale.

Other Games by Bob Fowler

Burma (GDW); Battles of Kohima and Imphal (Albion); March on India, 1944 (JagdPanther Publications).

Other Games of This Type

There are precious few games about China, and even fewer about the Chinese Civil War. The closest in similarity is Battle for China (Microgame Coop). Warring States (Simulations Canada) deals with internal strife in an earlier era (231 BC).

About the Author

John Nebauer has been boardgaming for over 21 years, ever since his science teacher introduced him to Diplomacy. His preference is for ancients and American Civil War, but he will play any period, although modern is his least favourite. When heís not gaming, he works in a mobile phone call center for the Australian telecommunications company Telstra, is a political activist in his current home town of Adelaide, and is also heavily into cricket and Star Trek.

Back to Simulacrum Vol. 2 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Simulacrum List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Steambubble Graphics

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com