Introduction

Crisis 2000: Insurrection in the United States!

GameFix 2 (Sacramento CA; Game Publications Group; November 1994)

The subtitle: The Forum of Ideas was dropped in issue 8; the publication was renamed Competitive Edge starting with issue 10. The company recently renamed itself One Small Step. GameFix/Competitive Edge markets itself as producing “wargames for people who don’t like wargames”. The conflict simulation games they offer with every issue of their magazine are deliberately designed to be simple to play (at least by wargame standards) and to be relatively quick and easy to finish (often less than an hour). GF/CE had also intended to feature non-military games

dealing with mountain climbing, various major league sports, etc. In the last few years, the publication schedule of the magazine has slowed to a crawl, and it is doubtless going through difficulties.

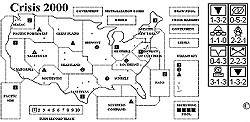

In tune with the aimed-for simplicity, Crisis 2000 has a map of the US consisting of 14 regions in total. They are of three types: metroplex, developed, and wilderness (the numerous black dots representing cities and military bases play no role in the actual game). There are also three boxes on the map representing US overseas deployment areas. The game has 100 counters. 55 represent military and political forces (units), 17 represent infrastructures and 37 are crisis markers used to augment the strength of one’s forces in different ways.

There are two notable things about the units/infrastructure counters. First of all, they are printed on both sides, showing the same formation (e.g. High-tech Arms division) in different colors, on different sides of the counter. This economizing measure is useful in terms of indicating immediate defections of military and political units as well as infrastructures to the other side, which is one of the main aspects of so-called Data Conflict. Secondly, the units have two values apart from their movement allowance: their ratings for Data Conflict and for Armed Conflict. There are special rules for certain units, for example, the Cybernauts usually cannot be attacked through Armed Conflict as they are presumed to be clandestine, while federal police forces can in some circumstances use their higher Armed Conflict rating against the Cybernauts. Ultimately, however, the game often simply amounts to “move in with your units and try to bash your opponent”, although the use of randomly-drawn Crisis markers to weaken your opponent or augment your own offensive, is critical to success. (The three numbers on a typical Crisis marker represent its conflict-augmentation values when committed to metroplex, developed or wilderness regions, respectively, for Data or Armed Conflict.)

The more combat and political forces committed to a given battle, the greater the chance of Collateral Damage, which impacts on the winner of the battle as well. The magazine’s background material to the game is highly interesting, although written from a very libertarian slant. It is a good beginning for speculations about possible future civil conflicts in the US, and for further analysis of the sociopolitical impact of the Internet. Game designer Joe Miranda points to the Clipper Chip controversy -- the attempt to create a microchip standard for all email encryption that would also allow for the decryption of all electronic messages through special keys held by government agencies. (The current standard is a plethora of commercially-available encryption programs which may often be virtually inaccessible to government monitoring.)

Miranda also writes about Operation Sun Devil, launched by the US Secret Service in 1990. Among the targets was a gaming company, Steve Jackson Games, whose cyberpunk roleplaying game, although dealing with fictional hardware and software, was considered to be so close to versimilitude as to constitute a how-to guide. The company faced great difficulties as all its computer equipment and files contained therein were impounded; however, it was eventually vindicated in court, while gaining great publicity on behalf of its products. One of the results of Operation Sun Devil was the formation of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which is one of the chief groups fighting for complete freedom of communication on the Internet (although it itself has sometimes been criticized by more radical groups for neglecting its mission).

The magazine also mentions a provocative article published in the Winter 1992-93 issue of Parameters, the U.S. Army War College’s journal, by Lt. Colonel Charles J. Dunlap, Jr., entitled, The Origins of the American Military Coup of 2012. The article’s main purpose appeared to be to critique the very deep cuts to the US military, but especially to protest the increasing use of the US armed forces for political ends, both at home and abroad. In the future, both these trends are seen as sapping US morale and combat effectiveness, to the point where a major US defeat in the Persian Gulf area causes the military to turn against its inept political masters, supposedly cheered on by much of the civilian sector.

Among the eclectic mixture of other references listed are James Burnham’s political classic, The Managerial Revolution and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. The game offers seven scenarios with differing force-mixes for the two opposing players (unlike many political games such as Diplomacy, this is strictly a two-player game). The seven main scenarios are:

- Coup 2001: The Military attempts to seize power from a corrupt civilian government.

- Culture Wars: The country splits wide open between Cyber-Futurists and Family Values Traditionalists.

- UN Occupation: The United Nations dispatches a peacekeeping force to suppress the outlawed American firearms, tobacco, and rogue computer industries.

- War on Freedom: The government makes a preemptive strike to clamp down on crime, local secessionist movements, unwed mothers, computer hackers, and other threats to the national security.

- Generation X: Everybody against the younger generation! (Or should that be, the younger generation against everybody else!)

- Anarchy in the USA: Various groups unite to fight for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- Civil War II: Fed up with the Feds, state and local governments declare independence, backed by their National Guards and unofficial local militias.

GameFix no. 9 presents a further scenario:

- The Militia War: The trend of the 1990s was toward forming local militias to protect the citizenry from real or imagined threats from criminals and government interference. By the year 2000, the Feds, deciding that the movement is too large and dangerous, launch an operation to disarm the militias.

Many of these scenarios are clearly rooted in a specifically American experience of the world. Although all of them point to identifiable social and political realities, the US fortunately seems rather distant from any of these metamorphosing into an actual shooting civil war (both the game and this review being somewhat ironic exercises).

One questionable aspect of the game would be what could be seen as its huge overrating of the impact of the Cybernauts and Internet. In the opinion of the reviewer, Cybernaut units should be reinterpreted as representing the media in general (or at least its most senior and activist persons). If a Cybernaut unit was seen as a massive agglomeration of media leaders, such as film producers and directors, key TV network people, hundreds of newspaper, book or magazine publishers, and the best-known investigative journalists, as well as the Internet activists themselves, then such a projection of power would seem more warranted. The merger of AOL with Time Warner shows the hunger for hard content as part of a successful Internet strategy, albeit much of what Time Warner offers is, admittedly, mere entertainment. Very many people today, however, fundamentally live and define themselves by their varied entertainments.

Another game inaccuracy, in the reviewer’s opinion, is the zero ratings of military units in Data Conflict. While the military might find it difficult to initiate political struggle, they are certainly among the most cohesive groups in society. Propaganda might degrade a military unit somewhat, but never to the point where it comes over to another side with fully intact combat and capabilities. It would probably break completely before changing sides. The strengths of irregular fighting formations also seem rather overvalued in relation to disciplined, cohesive military units, with heavy equipment.

It may be seen that the onset of a period of high prosperity and low unemployment in the 1990s put to rest the dangers of major upheaval in the US. However, the developments in social and cultural matters are more troubling. Indeed, the US continues to be engulfed by a series of bitter and highly divisive culture wars. One wonders what could happen should the bright noon of the stock market boom suddenly turn to darkness?

GameFix/Competitive Edge:

1. Thapsos and Alexandria (two battles of Julius Caesar)

2. Crisis 2000: Insurrection in the U.S.

3. Chicken of the Sea: Naval Warfare During the Punic Wars

4. Bombs Away!: The Air War Over Europe (card-based game)

5. Winceby: Battle of the English Civil War

6. Redline Korea: Potential Conflict in Korea

7. The BIG One: The War in Europe, 1939-1945

8. Greenline Chechnya: The Current Conflict in Chechnya

9. Among Nations: International Intrigue in the Modern World (card-based game of international diplomacy)

10. Edson’s Ridge: World War II, Battle for Guadalcanal

11. Cybernaut: The Duel for Cyberspace

12. der Kessel: Escape from Stalingrad/Battlechrome: Fire and Steel

13. Main Event (professional wrestling) / Hatfields and McCoys (satirical hillbilly game).

In 13, Joe Miranda’s Neuro Predators: Hyper Reality, a hex and counter board game pitting the military forces of a frightened empire against those of the cyber-chaos, was announced for the next issue. As far as the reviewer is aware, issue 14 has not yet appeared.

Back to Simulacrum Vol. 2 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Simulacrum List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Steambubble Graphics

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com