British Capture French Ships (# 119)

British Ultimatum (# 120)

At 1615 hours, Admiral Somerville sent the following signal to Admiral Gensoul: “If none of the propositions are accepted before 1730 hours - I repeat 1730 hours - it will be necessary to sink your ships.”

All hope was now gone; the battle would take place and under tragic conditions, as Admiral Gensoul had forbidden his ships to get underway during the negotiations lest this immediately bring on the fight. At 1656 hours, the British squadron opened fire. It had been 125 years since the French and the British had last fired on each other. It was at Waterloo. Throughout nearly all its long history, the French Navy had one principal opponent - England. Excluding the so-called ‘Hundred Years War’ their rivalry began when the expansionist ideologies of Louis XIV collided with the equally imperialistic ideas of William III of England.

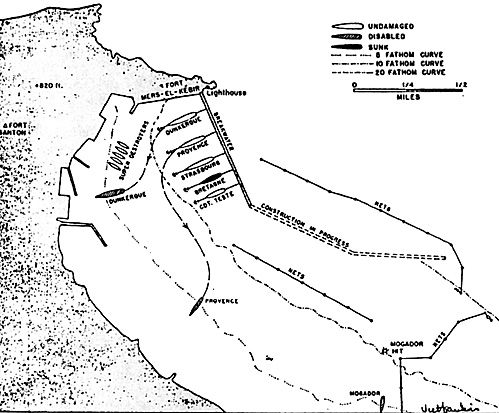

At that moment, Admiral Somerville was in a position north-northwest of and approximately 14,000 meters from Mers-el-Kebir lighthouse, with battleships in column on course 70 degrees, at a speed of 20 knots.

The first salvo landed north of and close to the breakwater. The order was immediately given to the French ships to open fire. Admiral Gensoul had no intention of fighting while at anchor, but in the crowded anchorage all of the ships could not get underway at the same time.

The French battleship STRASBOURG under command of Captain Louis Collinet, got underway within seconds. The berth she had just left was immediately struck by a salvo of British shells.

The other battleships were not so fortunate. The DUNKERQUE was struck the moment she slipped her mooring. A 380mm shell hit, followed by a 3 inch salvo, which caused serious damage and left her half paralyzed. With her electric power gone, she could not fire her guns.

The battleship BRETAGNE was also hit before being able to get underway. she began to sink by the stern, with an immense cloud of smoke rising above her. At 1707 hours, she was on fire from stem to stern and two minutes later, she suddenly capsized and sank, taking 977 men down with her.

The battleship PROVIDENCE was hit at 1703 hours. A serious leak and fire breaking out aft induced her captain to beach her.

The destroyers had all succeeded in getting underway. They would probably have gotten out of the harbour unscathed if the MOGADOR had not been forced to stop in the channel to avoid a tug. Seconds later, a 380mm shell struck her aft, setting off the 16 depth charges in their racks. With her stern blown off to the engineroom bulkhead, the MOGADOR anchored in three and one half fathoms of water, where small craft rushed from Oran assisted in putting out the fires aboard her.

The fire of the British had been very heavy, very accurate, and of short duration. At 1712 hours, Admiral Somerville ceased firing and took cover under a smoke screen. The French submarines from Oran were depth charged by British destroyers and did not succeed in getting within torpedo range of the British ships.

While the coastal batteries undoubtedly contributed to the escape of the battleship STRASBOURG and the destroyers by keeping the British largely to the western end of the bay by their intense firing. At 2010 hours the next day, the STRASBOURG entered Toulon along with the destroyers VOLTA, TIGRE and TERRIBLE where they were received with tremendous cheering from all the ships in the roadstead, where they were to be joined shortly by six cruisers from Algiers.

The British submarines HMS PANDORA and HMS PROTEUS, patrolling to the north of Algiers and Oran respectively, had not taken part in the Mers-el-Kebir battle, but at 2150 hours on July 3rd, they received orders to attack all French Men-Of-War on sight. The next afternoon, HMS PROTEUS sighted the COMMANDANTE TESTE but could not get into a firing position, but HMS PANDORA, commanded by LCDR ‘Tubby’ Linton, torpedoed and sank the colonial sloop RIGAULT de GENOUILLY ten miles north of Algiers.

During the night of July 5th, Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, had Vice Admiral Jean Odensihal (French Admiralties sole liaison office with the British Admiralty) awakened in London especially to tender him his regrets at this torpedoing. It was due, he said, solely to an error on the part of the Royal Navy, while the attack at Mers-el-Kebir had been strictly a decision of the British Government, and the Royal Navy could do nothing except obey the order to attack had been given to the submarines by Admiral Sir Dudley North, Flag Officer Commanding in the North Atlantic at 2316 hours on July 4th.

The encounter at Mers-el-Kebir almost resulted in what had been predicted by Admiral Gensoul and feared by the British themselves - a complete about-face by the French Navy, which up to then had been 100 per cent pro-British. During the night of July 4th, a few French naval planes were sent to attack the British fleet at Gibraltar, but no hits were scored.

On the 4th July, in answer to the attack on Mers-el-Kebir, the French submarines stationed out of Dakar LE GLORIEUX and LE HEROS, and the auxiliary cruisers ‘EL DJEZAIR, EL MANSOUR, EL KANTARA and VILLE D’ORAN and the destroyers EPERVILLE and MILAN already in Dakar, received orders to attack all British ships, by Admiral Darlan, Commander-In-Chief of the French Navy under the Vichy French Government. Also on the 4th, the Vichy French Petain Government breaks off diplomatic relations with Britain.

On 6th July, the British return to Mers-el-Kebir and at dawn, three waves of torpedo planes from HMS ARK ROYAL attack the ships still in the roadstead. The anti-aircraft defenses only partially broke up their attack. A torpedo hit one of the small craft which were grouped around the battleship DUNKERQUE to assist in repairing her. The torpedo exploded the depth charges on the small craft, which in turn blew a large hole in the side of the DUNKERQUE, killing 150 men.

Meanwhile, at Alexandria and Dakar, French and British relations had come to near crisis. At Alexandria, Admiral Cunningham had received orders to seize the ships of Vice Admiral Rene Godfroy on the same pattern as Admiral Sommerville at Mers-el-Kebir but here the situation was even more delicate. The French ships had been operating as an integral division of Admiral Cunningham’s force. In fact, they had been scheduled to take part in a combined operation on June 22nd, which the British had canceled at the last moment.

Then during the night of the 24th, Admiral Godfroy received orders from the French Admiralty to leave Alexandria at the earliest possible moment. But Admiral Cunningham had likewise received very definite orders from his Admiralty. In view of these, he had respectfully asked Admiral Godfroy to remain in port.

Admiral Godfroy did not insist on leaving and he did not wish to provoke a bloody engagement which could benefit no one except the enemy. No French sailor will ever forget the chivalry and the intelligence which Admiral Cunningham displayed in arriving with Admiral Godfroy at a solution to the crisis on July 3rd.

A brutal application of the orders of the British Admiralty would undoubtedly have resulted in a tragedy, as at Mers-el-Kebir. Admiral Cunningham was fundamentally hostile to the ‘senseless’ operation which he knew was taking place at Mers-el-Kebir at that moment. The day of July 3rd passed without any tragic incident. Both admirals had agreed to maintain the ‘status quo’ until the next day. However, when the news of the attack at Mers-el-Kebir was received on the flagship DUQUESNE, Admiral Godfroy hardened immediately.

Back to KTB #121 Table of Contents

Back to KTB List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Harry Cooper, Sharkhunters International, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles articles are available at http://www.magweb.com

Join Sharkhunters International, Inc.: PO Box 1539, Hernando, FL 34442, ph: 352-637-2917, fax: 352-637-6289, www.sharkhunters.com