Agricola took up his duties in Britain in the year 78. He was two

years campaigning in North Britain and Wales before he felt secure

enough to begin his advance into Scotland.

Agricola took up his duties in Britain in the year 78. He was two

years campaigning in North Britain and Wales before he felt secure

enough to begin his advance into Scotland.

The northern Celts had not been unaware of the Roman advance to the north. One hill fort thought to have been strengthened at this tine was The Chesters in East Lothian. It had received extra ramparts.

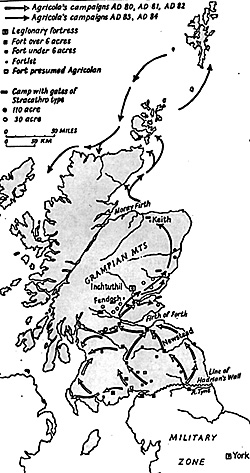

The great project began in the year 81. The Romans launched across the Tyne and the Edin into the territory of the Selsoyae and Votadini in two columns. One army moved up the Annan River valley, the Annandale, and the other through Lauderdale. The terrain along both axis of advance was extremely rough and varied. Progress was difficult, but there was little resistance The Celtic inability to act In concert and attack the eneny at this juncture lost then a golden opportunity to catch the Romans at a disadvantage in unfavourable circumstances

The two colunns re-united at Inveresk, then together penetrated further into the land between the Forth and the Clyde. Forces were filtered off to the southwest into Galloway to deal with another tribe, the Novantae.

The next year was spent securing the newly overrun areas and planting a number of garrisons in forts between the Clyde and the Forth, which would later be incorporated into a new frontier, the Antonine Hall. To quote Tacitus, "The enemy had been pushed into what was virtually another island."

Final Push

By the year 83 Agricola was ready for the final push. This phase of the campaign was carefully thought out and executed. Both the east and west coasts were reconnoitered by sea, exploring the possibilities of an amphibious attack fron either direction. A direct advance into the Highlands would have been folly.

The heavy Roman infantry would have been at a distinct disadvantage against an extremely mobile foe who knew the difficult terrain and was expert at ambush. Geography ultimately decided the form of the campaign.

The army would march up the eastern coastal plain. Forts would be built at the mouths of the sleas which opened to the plain. Those would provide a chock to assaults on the line of supply. The army would also lie supplied through the efforts of the fleet, which would be well able to provide uninterrupted Support in men and material to the advancing legionaires.

Thirty thousand troops folllowed their standards northwards. Their route is thought to have been through Strathallan, Strathearn, Strathmore and beyond to Stirling, then on to the foothills of the Grampians. It was then that the resistance of the Caledonians stiffened, and one can sense the presence of the Shadow war chieftan Calgacus planning, organizing and inspiring the wild highlanders. They attacked a Roman fort with such determination that it appears some advocated a dignified retreat to behind the Forth. The Romans, however, beat then off, regrouped and pushed on.

Briton Attack

The Britons were not dismayed. They next made a fierce night assault on the camp of the legion IX Hispana. This was a nasty bit of business for the Romans. The sentries were killed and the perimeter broached. The situation was only retrieved by the quick reaction of Agricola himself, who was able to bring the entire army by dawn and take the Caledonians in the roar. The canny highlanders faded into their forests and marshes. They may have been a more serious check to the Romans than Tacitus wanted us to know. We hear of no further initiatives on their part until the next year.

84 A.D. Was the last year of Agricola's governorship of Britain. Large events build their own momentum. The fleet barraged and plundered the coastal areas. The Caledonians rallied to Calgacus, a potent and ever increasing force, and the persistent Romans doggedly continued their advance northward to Mons Graupius.

Where was Mons Graupius?

The site of the battlefield is not known with certainty. In 1978 J.X. St. Joseph and David Wilson of the Cambridge University Areial Photography Unit published results of their research making a strong case that the long sought location is in the hill mass of Bennachie, five and one halt kilometers southwest of Durno, (the site of an Agricolan camp).

Tacitus sketches the Roman dispositions with detail. The legionaires formed a reserve outside the ramparts of the camp. In front were eight thousand auxiliary infantry with three thousand cavalry divided between the flanks, and led by a commander, who in the heat of battle would fight on foot at the head of his men.

Thirty thousand Caledonians faced thenmdrawn up in tiers on higher ground, fearless warriors, tall, fair or red haired ... in primitive tartan, shields and helmets gay with enamel. They were followed by thousands of haft naked, bare-footed infantry, bearing small wooden shields with a boss, and armed with spears with a knob at the end which could be clashed with terrifying noise.

In the space between the armies the British aristocracy furiously manoeowed their chariots while hurling abuse at their foe and boasting of their prowess in true Celtic fashion.

The action commenced with the usual exchange of missills, followed by the advance of six cohorts of Batavi and Tungri auxiliaries, Germanics from the mouth of the Rhine. Nobody could describe it better than Tacitus.

- "The Maneuver was

... most inconvenient to

the enemy with their small

shields and unwieldy

swords -- swords without a

thrusting point, and

therefore unsuited to the

clash of arm in close

fighting. The Batavi began

to rain blow after blow,

push with the bosses of

their shields and stab at

their enemies in their

faces. They routed the

enemy on the plain and

pushed on uphill. This

provoked the post of our

cohorts to drive in bard

and butcher the enemy as

they met him. Many Britons

were left behind half dead

or even unwounded, such

was the speed of our

victory."

The Caledonians tried an outflanking movement which was repelled by an uncommitted cavalry reserve. Next, the Romans issued a flanking manoeuvre of their own which met with success. Tacitus again speaks:

- "The spectacle that

followed over the open

country was awe-inspiring

and grim. Our men followed

hard took prisoners and

then kilied them ...on the

enemy's side ... some

bands, though armed, fled

before inferior numbers.

Some men, though unarmed,

insisted on charging to

their deaths. Weapons,

bodies, severed limbs lay

all around and the earth

reeked of blood."

The victory was complete and decisive. It was claimed ten thousand Britons had died, for the loss of three hundred and sixty on Roman side, Once more we go to Tacitus:

- "The next day

revealed the quality of

the victory more

distinctly. A grim silence

reigned on every hand, the

hills were deserted,

only here and there was smoke

seen rising from chimneys is the

distance, and our scouts found no

one to encounter them."

Next issue we shall examine the quality at that Roman victory. After all, the frontier was eventually established far to the South. Was it a victory? We shall also reveal sent astounding facts about the great Legion Fortress built at Inchtuthil at a respectable distance north of the Clyde - Forth line.

Back to Saga v3n6 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com