Bernard Cornwell’s latest series of novels, “The Grail Quest”, is set during the early part of the Hundred Years War. The first novel in the series, “Harlequin/The Archer’s Tale”, saw the young hero, Thomas of Hookton, serve as a longbowman at the battle of Crecy in August 1346.

Bernard Cornwell’s latest series of novels, “The Grail Quest”, is set during the early part of the Hundred Years War. The first novel in the series, “Harlequin/The Archer’s Tale”, saw the young hero, Thomas of Hookton, serve as a longbowman at the battle of Crecy in August 1346.

Somewhat unexpectedly, the start of the second novel, “Vagabond”, finds Thomas and his travelling companions outside the city of Durham on the eve of the battle of Neville’s Cross in October 1346. They are seeking information on the whereabouts of the Holy Grail when they come upon a Scots army intent on sacking Durham and its great cathedral dedicated to St. Cuthbert. Unsurprisingly, Thomas elects to serve in the army of the northern English nobles, whose commander is the Archbishop of York.

There follows a very vivid description of the ebb and flow of the battle, as first one side, then the other, has the upper hand. Cornwell is particularly good at bringing out the brutal nature of medieval warfare, whether in his description of hand-to-hand combat or of the effect of the longbows on unarmoured Highlanders. He also highlights the effect of terrain on the outcome of this battle.

I think the battle of Neville’s Cross makes an excellent scenario for Medieval Warfare.

Historical Background

Following his crushing victory over the French at Crecy, Edward III marched to besiege the port of Calais. In response to this, Philip VI of France called upon King David II of Scotland to launch a diversionary invasion of northern England. With such a large proportion of the English army campaigning in France, the Scots were confident of success. King David personally led a Scots army of over 12,000 men southwards. His immediate intention was to capture the mighty fortress stronghold of Durham. In reply, a small English army of some 5,000 men under the overall command of the Archbishop of York hurriedly moved northwards from Yorkshire to reinforce Durham and to confront the Scots army.

THE BATTLE

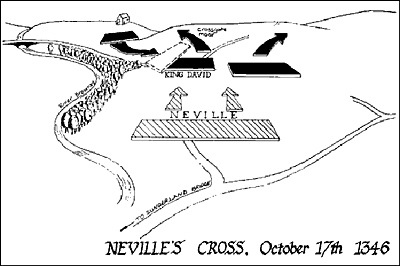

On the morning of 17 October 1346, the Scots army was arrayed in three divisions on a high but narrow ridge just to the west of the city. Tantalisingly close to the east of them, they could see the great prize - Durham’s Cathedral and Castle. However, to the south they could also see the English army drawn up in four divisions, three to the front and one held back in reserve. Confident of victory not least because of superiority of numbers, David ordered his soldiers to advance towards the English lines. Almost immediately, the Scots division under Sir William Douglas on the west flank found that to attack the English division in front of it involved descending into a steep-sided valley and then clambering up the other side. This first misfortune was soon greatly magnified by a second.

The English division led by Sir Thomas Rokeby that overlooked the struggling Scots soldiers on the west flank happened to contain a strong force of English archers. At this time, the English longbow, with its great range and the power to pierce armour, was one of the most terrifying weapons to be found on any medieval battlefield. Almost at once, this advancing division - a third of the Scots army - started to disintegrate as wave upon wave of deadly arrows flew down from above. Soon, Douglas's division began a headlong retreat in a state of complete confusion.

On the east flank, by contrast, the Scots division under Lord Robert Stewart, the heir to the Scots throne, was having considerable success. It managed to roll back the division of the English army led by Lords Neville and Percy that stood in its way. However, in doing so, it exposed its own flank to the English reserve. Finding itself now under attack on two sides, this Scots division too began to fall back.

As the Scots divisions on either flank retreated, the central division commanded by King David himself was left exposed to attack on three sides. It was thus in an increasingly desperate position. In due course, David himself was wounded and his standard bearer killed. At this point, the central division of the Scots army also broke and ran.

King David was captured a short time later and spent more than 10 years as a prisoner of Edward III. Much of the Scottish aristocracy was either killed or captured.

As before at Northallerton and later at Flodden, Scotland had tried to take advantage of England’s difficulties, only for the Scots to suffer a bloody reverse.

THE REFIGHT

It is clear from descriptions of the battle that the terrain played a major role in determining the outcome of the battle. Cornwall provides an excellent description of the battlefield, one that I see no reason to disagree with. The three Scottish divisions on the ridge were cut off from each other by stout hedges. Due to poor reconnaissance, the Scots on the right were unaware that the English flank was anchored by a steep valley. Furthermore, the English centre was protected by a stone wall. Only on the Scottish left were there no obstacles. Skilful use of the terrain by the English helped to negate the large numerical advantage enjoyed by the Scots.

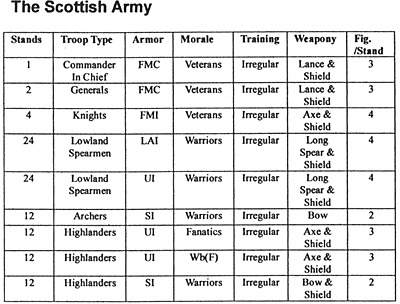

Scots

Scots

- The Scottish Army should be deployed in three similarly sized divisions

- Lowland Spearmen may be in mixed armor units

- Should you require a priest, the Archbishop of St. Andrew's was there; he was later captured.

English

English

- The English should be deployed in three divisions with a small mounted reserve.

- The majority of English knights are classed as AC/FMI rather than FPC/FPI to reflect the fact that the best knights were serving in France.

- Some of the Shire Militia are fielded as UI to reflect the citizens of Durham who were pressed into service to meet the emergency.

- Longbowmen and Shire Militia may be in mixed armour units.

- Should you require a priest, the Prior of Durham Cathedral and a group of his monks prayed throughout the battle on a nearby hill under the banner of St. Cuthbert.

Special Factors

- King David II was a young inexperienced general who, though brave, showed himself to be tactically inept. He was desperate to prove himself the worthy son of Robert the Bruce.

- As the battle took place on a ridge down which the Scots charged, advancing Scottish units will count as moving downhill.

- The table will represent the entire ridge with the English army’s flanks protected by a river-ravine on the left and a steep slope on the right. It may be necessary to reduce the width of the table to reflect the fact that the Scots were forced to deploy on a narrow frontage due to the narrowness of the ridge.

- The wall covering the central English division counts as an obstacle.

- The river-ravine on the English left also counts as an obstacle.

Back to Saga # 90 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com