The Historical Context

With the downfall of the Sui Dynasty (589-618 C.E.), a confusing complex of claimants to the Dragon Throne marched and countermarched across the high plains of China proper. The land swarmed with a dozen large rebel armies, variously led by former Sui generals, provincial officials, bandits, rogue soldiers, and barbarian chieftains. Li Shih-min, already an experienced and charismatic military leader at the age of 22, had defeated several of these rival forces, driven back several others, and captured the Sui capital, Chang An - the city of 'Eternal Peace,' with an army that had expanded over the course of the campaign to nearly 200,000 troops. Having elevated his father, Li Yuan, to be the first emperor of the new Tang Dynasty (618-906 C.E.) under the title of Tang Gao Zu ("Highest Ancestor of the Tang"), Li Shih-min spent the next two years stabilizing central China using a combination of brilliant generalship and sensible diplomacy.

However, in the year 620 C.E., a new danger to the young dynasty rumbled out of eastern China in the form of the huge army of Dou Jian-de, who was one of the earlier rebels against the Sui, and who had set up a rival dynasty called the Xia in the region north of the Yellow River near the eastern coast of China - with himself as emperor.

As a prelude to this new challenge, a Sui general called Wang Shi-chong had quartered himself in the eastern capital of Luoyang, claiming continued loyalty to a prince left over from the now defunct Sui. Wang, noted as a cruel and stupid leader, attempted an advance up the Yellow River against the Tang, but was easily pushed back into his fortress city. At this point, Wang allied himself with Dou Jian-de, who took his time about mobilizing. Li Shih-min took advantage of this hiatus to invest the region around Luoyang, and place a garrison in the walled town of Sishui located 50 km east of Luoyang. This latter move was designed to guard the road leading directly from the territory of Dou Jian-de.

The siege of Luoyang was marked by raids, sorties, assaults, bombardments with catapults and bolt-shooters, and at least one major battle just north of the city. When the large Xia army of some 300,000 troops was reported in the east moving inexorably towards Sishui, Li Shih-min's generals exhorted him to lift the siege and fall back to the west. Li decided instead to leave the bulk of his army to continue the siege and move against Dou Jian-de before the latter reached Sishui.

Initially taking 10,000 elite horsemen, Li rode eastwards and deployed in a line on the heights to the north and south of Sishui town. He also put a significant diversionary force across the Yellow River on its northern bank.

The Terrain

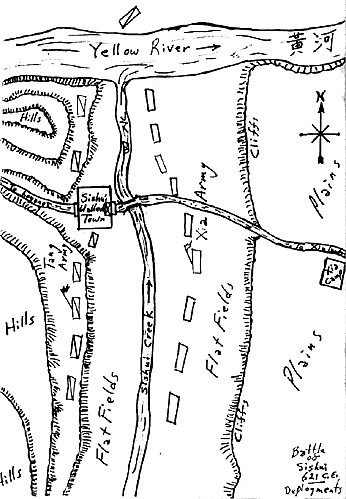

The fortress town of Sishui took its name from a shallow creek that runs from south to north past the eastern side of the town. The 1,500 meters wide Sishui junctions almost perpendicularly with the eastward flowing Yellow River to the north of the town. A line of steep hills running parallel to the creek all the way to the edge of the Yellow River was broken only by a small gap through which passed the road westwards to Luoyang. The walled town of Sishui blocked this pass.

Upon exiting the town, the road crossed Sishui creek bridge, and then headed almost due east - directly into the territory of the Xia emperor. Only a north-south running cliff broke the low plain on the eastern side of the Sishui. Another plain stretched to the east of this cliff. It was here that Dou Jian-de camped his army.

The Battle

Li Shih-min is noted as one of the few generals in history who was supremely sensitive to using time and weather as major weapons. Li demonstrated this well at Sishui. Small units of both heavy and light Tang cavalry thrashed across the shallow creek and skirmished continuously with the Xia horsemen. Feigned retreats into ambushes, night attacks on the Xia camp, and continuous frontal and flanking feints kept Dou Jian-de in a state of hesitation and doubt. As each day passed, hunger and attrition brought Luoyang closer to surrender, allowing units of the besieging force to move eastwards quietly to swell the size of the Tang forces at Sishui.

Ranitzsch points out another aspect of time as a weapon at this engagement. He states, "The ships with supplies for Dou Jian-de's large army had to be moved laboriously up the Yellow River, while those carrying the goods for the much smaller Tang army could float down stream." (Karl Heinz Ranitzsch, The Army of Tang China, Montvert Publications, 1995, page 62.) Li compounded Dou's problems by sending raiders to attack his supply convoys.

Relieving Luoyang quickly became the compelling motivation for Dou's decision to try to force his way directly through the main road westwards, rather than take the long way around the Tang flank by crossing the Yellow River to the north. Reports of Tang forces already being located on the north bank suggested that such a flanking maneuver would be contested anyway, possibly during the river crossing itself.

Dou did not want to assault the Sishui fortress directly, and so deployed his forces along the plain between the eastern cliffs and Sishui creek - stretching his line seven miles, with his right anchored on the south bank of the Yellow River. Dou hoped the Tang army would come out to fight in the open. Li did not move. Tang skirmish horse would occasionally dash forward through the shallow stream, fire, and flee. Li watched as the hot summer sun baked down on his enemies standing on the open plain . . . and waited.

By midday, heat, hunger, fatigue, anxiety and frustration caused increasing numbers of Xia army units to break ranks seeking food, water and shade. Sorties across the creek by Tang horse archers revealed the Xia army to be in a general state of disorder. And, the Xia generals had gone back to their camp, arguing amongst themselves, and with Dou, on a course of action. At this moment, Li ordered his entire army to advance across the Sishui, and attack. The entire Xia army was in confusion. Their infantry found it impossible to reform in any semblance of battle order. Their cavalry managed to recreate a line after being pushed back near the base of the eastern line of cliffs. But this was to no avail. Li Shih-min's eighteen-years-old cousin, Li Dao-xuan, led wedges of fully mailed cavalry through the Xia line, circling back to smash through again from their rear.

Finally, when the Tang standards were displayed above the cliffs behind the Xia army, the latter broke into flight. In the pursuit, some 50,000 prisoners were taken. Dou Jian-de was captured alive, and his army was completely destroyed. The spurious Xia Empire was no more.

Li Shih-min now turned to the job of conquering the rebel kingdoms along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River valley.

The Scenario

Developing army lists for tabletop gaming of this battle poses some interesting problems. The greatest of these is the large disparity in the relative sizes of the respective forces. The official Tang histories would have us believe that Li Shih-min pitted a mere 10,000 cavalry against a Xia army totaling 300,000 horse and foot. Since the winners write the histories, we can reasonably assume a bit of exaggeration in the tally of the loser's army, i.e., 300,000 does seen a bit much. Nevertheless, while there is evidence justifying the assumption of a larger number for the Tang forces at this engagement, we are still left with a huge imbalance.

A key to achieving a better balance for miniature wargaming this battle would seem to be the large difference in morale and leadership held against the difference in army sizes. Thus, history justifies giving the smaller Tang army better quality generals, higher morale, good defensive positioning, and initiative. The larger Xia army would have between two and three times the number of stands (or units), but with low morale, mediocre generals, and exposed field positioning. Even more, the battle would start with the Xia generals all back in their camp, i.e., outside command range, and with many of their front line units in disordered condition.

Some play testing of this scenario may expose a need for modification of the initial orders-of-battle and troop qualities in order to eliminate as much as possible the imbalance of respective army sizes. Feedback to the editor of SAGA from anyone who tries out this battle would help achieve any necessary modifications.

Given that archery has always been a dominant feature of Chinese armies of both ancient and medieval periods, the supply train option (in MW rules) was given much consideration for this scenario. First, the Tang had convenient and open supply lines. They controlled the upstream portion of the Yellow River, as well as the road from Sishui to Loyang, and from there all the way westwards to Ch'ang An. Second, the walled town of Sishui served as a just-behind-the-lines supply depot. To reflect this advantageous situation, the Tang army is given 3 supply trains to keep their troops supplied with arrows. In addition, Sishui fortress itself is regarded as a 4th supply source.

On the other hand, while the Xia controlled the Yellow River downstream, their ships had to move upstream against the current, with the ever-present danger of raids by Tang warships, and a longer road from their home territory on the east coast of China. Also, the Xia's larger army needed far more supplies of every kind than the Tang. Thus, the 'pretender's' army gets only 2 supply trains.

To reflect the imbalance in generals, Li Shih-min, the CiC, is classed as "Charismatic," allowing him to issue 5 orders per turn. His young cousin, Li Dao-xuan, is classed as "Brave," with 4 orders per turn. The Tang gets one (1) additional general (i.e., a total of 3 generals), who must roll for his command ability rating. On the opposite side, Dou Jian-de, the Xia CiC, is classed as "Stalwart," with only 3 orders per turn. Their remaining three (3) generals must roll the dice for their rating. (Note that the Xia gets a total of 4 generals.) Furthermore, for the first three (3) moves, the Tang army holds the initiative. Thereafter, both CiCs must roll for initiative as per MW rules.

Note that there are no "God" rolls for these theologically eclectic and practical-minded Chinese.

All Xia generals, including the CiC, begin the battle at their campsite - outside command range from their respective commands. Two-thirds of Xia infantry, and one-third of Xia cavalry begin the battle in a state of disorder. The troops deployed closest to the creek must receive the disordered designations.

The rules for river crossings under MW's "Terrain Effects" are suspended for Sishui creek. Horse troops of either side may pass freely across the creek at any point at half their movement allowance. Elite, veteran and/or trained cavalry are not disordered while moving through this shallow stream, but cannot charge. All others are disordered while in the water. Infantry can also pass at half their movement allowance, but all are disordered while sloshing about in the creek.

Both sides get two (2) river transports at no point cost. These can move only on the Yellow River - Sishui creek is too shallow for large boats. The Tang ships start upstream (i.e., to the west), and moored to either the north or south bank. The Xia ships start downstream, and moored to the south bank.

The historical battlefield terrain and approximate initial troop deployments are indicated on the sketch map accompanying this article.

The Tang Army

1x CiC (Li Shih-min), FMC Elite (T), L/B/Sh, 3@58

1x Gen'l (Li Dao-xuan), HC Elite (T), L/B/Sh, 3@41

1x Gen'l, HC Veteran (T), L/B/Sh, 3@39

4x Guard Cavalry, FMC Elite (T), L/Sh, 3@17

8x Nobles, FMC Veteran (T), L/Sh, 3@15

4x Heavy Cavalry, HC Veteran (T), L/B/Sh, 3@14

4x Heavy Cavalry, HC Warrior, L/B/Sh, 3@11

4x Tu-jue (Turkish Allies), HC Warrior, L/B/Sh, 3@11

16x Light Cavalry, SC Warrior (T), B/Sh, 2@5

6x Guard Infantry, HI Elite (T), Halberd or Long Spear, 4@9

3x Supply Train @ 35

2x River Transports

Total Number of Fighting Stands: 53

The Xia Army

1x CiC (Dou Jian-de), FMC Veteran (T), L/B/Sh, 3@561x Gen'l, HC Veteran (T), L/B/Sh, 3@39

2x Gen'ls, HC Veteran, L/B/Sh, 3@38

4x Guard Cavalry, FMC Veteran (T), L/B/Sh, 3@16

4x Heavy Cavalry, HC Veteran, L/B/Sh, 3@13

4x Heavy Cavalry, HC Warrior, L/B/Sh, 3@11

4x Light Cavalry, SC Warrior, B/Sh, 2@4

4x Light Cavalry, SC Warrior, Jav/Sh, 2@4

6x Heavy Infantry, HI Veteran, Halberd or Long Spear, 4@7

72x Militia Foot, UI Poor, LSp/Sh or B/Ssh, 4@3

72x Militia Foot, UI Poor, B or CB, 4@2

2x Supply Train

2x River Transports

Number of Fighting Stands: 174

Note: FMC in both armies may form wedge.

References

Fitzgerald, C. P. Son of Heaven: A Biography of Li Shih-min, Founder of the T'ang Dynasty. Originally published by Cambridge University Press, 1933. Reprinted by Ch'eng Wen Publishing Co., Taipei, 1970.

Ranitzsch, K. H. The Army of Tang China. Montvert Pub., Stockport, U.K., 1995.

Sima Guang (1009-1086). Zizhi Tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government). Completed in 1084 C.E. Annotated by Hu Sansheng (1230-1302). Reprinted by Hong Yeh Book Company, Taipei, 1973.

Tang Changru. Tang Shu Bing-zhi Jian-zheng (Notations on the Military Annals of the Book of Tang). Science Publishing Co., Beijing, 1957.

Back to Saga #78 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com