For this issue, I chose the battlefields of Verdun as a complement to the play testing of “Verdun Warfare” by Mitch Abrams at Historicon. I visited the area as the last stop on a battlefield tour of northwestern Europe in 1992 (the 50 th Anniversary of Dieppe, but I shall leave that for another time) that covered well-known actions of both World Wars. The stop was out of context for the theme of the tour as the aim was to visit battlefields on which Canadian soldiers fought in the two conflicts. Verdun was included as it was along the return route of the tour.

The Battle of Verdun was a series of actions from 21 February 1916 until 19 December 1916 between French and German forces. There were about 550,000 French and over 400,000 German casualties (dead, wounded and missing). These numbers include 143,000 German dead and about 163,000 French fatalities (about 50% of all casualties).

It was one of the costliest battles of World War One, and exemplified the 'war of attrition' pursued by both sides, which cost so many lives, and yet gained so little ground. By the winter of 1915-16, General Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff, was convinced that the war could only be won in the west. He decided on a massive attack on a French position. Falkenhayn targeted the town of Verdun and its surrounding forts as they threatened German lines of communication and lay within a French salient (a bulge in the line), restricting their defenders. A Gallic fortress before Roman times and later a key asset in wars against Prussia, Falkenhayn also knew that the French would throw as many men as necessary into its defence, enabling him to inflict the maximum possible casualties. The aim was to “bleed the French army white” thus forcing France out of the war and leaving the British as the main opponent on the western front (or more optimistically withdraw from the war).

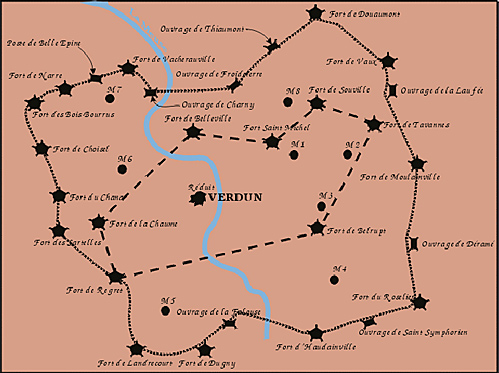

Verdun was a garrison-town situated in the Region Fortifée de Verdun (RFV) on the River Muese about 200 kilometres east of Paris. It was surrounded by a double circle (largest diameter about 50-km) of 20 large forts and 40 smaller fortifications in an almost impenetrable hilly country, covered with woods, criss-crossed with deep clefts and gorges through which the Meuse flowed. Following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the French military needed a new series of “frontier forts” to safeguard northeastern France from future Prussian/German attacks.

Verdun was selected as one of the major fortification zones and construction of up-to-date fortifications began in 1875. Unfortunately, the German artillery reduced several of these major strongpoints to rubble in 1914,and the French military decided that its pre-war construction was rendered obsolescent by the powerful artillery of its foe. Many of the remaining fortresses were abandoned and the garrisons (and their artillery) deployed elsewhere to defend the trenches that developed along the Western Front from the English Channel to Switzerland.

This map shows the layout of the two rings of fortifications surrounding Verdun built between 1875 and 1914. Note that Fort de Douaumont is in the top right corner.

The German operation was entrusted to the German Crown Prince Wilhelm, commander of the Fifth German Army, who was given substantial reinforcements by von Falkenhayn. The Crown Prince was ordered to commence the operation on 15 February 1916; however, the initial assault was delayed due to bad weather until 21 February. The German attack began with an intense artillery bombardment of the forts surrounding Verdun. The French army retreated to predetermined positions while the German army pounded through the French lines.

On 25 February 1916, Fort de Douaumont, near Verdun, surrendered to German forces. On that same day, General Joseph Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, dedicated to ceasing further French retreat, assigned General Henri Philippe Petain (later the leader of Vichy France in WW2) to command the French army at Verdun. Petain fought with the motto " Ils ne passeront pas," which means, "They shall not pass".

This was just the type of strategy that von Falkenhayn hoped that the French would adopt. To give an impression of the French tenacity, 259 of the French Army’s 330 infantry regiments served at Verdun over the course of the battle. The Germans maintained their momentum until mid-year despite increasing French resistance.

With the start of the Battle of the Somme (planned to distract the Germans from Verdun), the Crown Prince’s forces were reduced as German troops were sent westward the thwart the new Allied offensive. Despite the failure of the Somme operations to produce an Allied breakthrough, the French were able to regain ground around Verdun and declare a victory before Christmas Day 1916. Unfortunately, it was achieved with a massive number of casualties, and so at best ranks as a “Pyrrhic victory”.

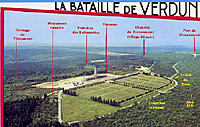

This is a postcard of an aerial view of the ossuary and Fort de Douaumont. There are 15,000 graves in the cemetery and roughly 130,000 bodies inside the ossuary.

This is a postcard of an aerial view of the ossuary and Fort de Douaumont. There are 15,000 graves in the cemetery and roughly 130,000 bodies inside the ossuary.

Large Photo of Postcard: Ossuary and Fort de Douaumont

My tour of the battlefield encompassed the city of Verdun and a long stop at the location shown in the first postcard. The Ossuaire or Ossuary in English (or bone yard) is the resting place of many of the unknown dead of the 10-month battle. These include both military and civilian casualties. Despite French efforts to glorify this battle, the ossuary and the nearby cemetery reflect the heavy losses of such battles of attrition.

The “tranchee des Baionettes” (Trench of bayonets) is another grim reminder. It is a mass grave for French troops who were preparing to “go over the top” when they were all smothered by earth thrown up by an artillery shell explosion. All that remained were the tips of their bayonets, which have either broken off or been taken as souvenirs in the intervening years.

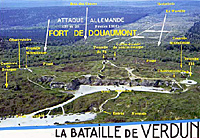

Much of the battlefield is now covered by trees that mask the many scars left by the actions of thousands of artillery pieces. These are more evident in the second postcard, which clearly shows the pounding that the fort received. It is possible to walk in the fosse and along the top of the fort.

This postcard depicts Fort de Douaumont from the interior (French position) with the original German lines in the background.

This postcard depicts Fort de Douaumont from the interior (French position) with the original German lines in the background.

Large Photo of Postcard: Fort de Douaumont

Ironically, despite the French Army’s 1914 assessment of limited potential of fortifications, it did not deter the creation and construction of the Maginot Line prior to 1939. Once again France focussed only on its border with Germany along which the massive fortifications were built. As a result to German armies concentrated on invasion routes through Belgium to first by-pass and later encircle the French main defensive line.

If you do visit Verdun, be warned that the area is still littered with unexploded objects including bullets and artillery shells. Be careful where you walk and do not go looking for such things.

If you do visit Verdun, be warned that the area is still littered with unexploded objects including bullets and artillery shells. Be careful where you walk and do not go looking for such things.

This is an aerial view of Fort de Douaumont after being bombarded. Note that the shelling has blurred the clean lines of the pre-war structure.

This is a diagram of the fort before the battle. Note the size of the post-battle structure, which has significantly been reduced by artillery bombardment.

Back to Sabretache # 3 Table of Contents

Back to Sabretache List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com