Quasi-historical Background

Quasi-historical Background

In several past issues of the REVIEW, I've described the exploits of the 999th Marine Division in the Pacific during WW II, in particular, their beach landings on Wallio Island. Just after they took Wallio Island, they then captured Wampus Island, some 100 mile to the north. But General Yama, Japanese Commander of the Highly Imperial Pacific Defense Force, was determined to recapture Wampus Island and he launched the assault described in this article. Note that this was one of the rare times that, late in the war, a Japanese force performed an amphibious assault on an American-held island.

In this superb historical re-creation of the Japanese landings on Wampus Island, I used the following:

- (a) First, the men in the Lannigan Brigade, 20mm figures acquired from Jerry Lannigan some time ago.

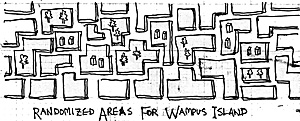

(b) A ping-pong table-sized map of irregularly drawn areas, each area at least 6 inches square to enable it to hold a couple of stands (infantry, tanks, etc.) of 20mm figures.

(c) I defined a battalion as 2 stands, whether of infantry, tanks, etc. I defined the 'stacking limit' per area as two stands, i.e., one battalion.

(d) I permitted an infantry battalion to be reinforced with a stand of either an anti-tank gun, or a machine gun.

(e) There were about 50 areas on the field. I placed terrain items in most of them... items such as woods or 'houses' (denoting built-up areas).

In the fire phase, tanks were given a range of 3 areas. Due to the presence of blocking terrain, the range would normally have been limited to a single adjacent area. But in order to open up the game, I permitted these long-range weapons to fire for 3-areas, even if blocking terrain was present.

Each covered area through which a tank fired deducted something off the probability of hit (POH). Which brings up the question... how large a region does an 'area' represent? Is it a field, or a couple of acres, or 4 or 5 football fields, or a half-county? I shall side-step this thorny question, and merely note that permitting a tank to fire through a built-up area, or through woods, essentially means that the area itself was not completely covered... the terrain items could be said to 'sparsely cover' the area, so that a target beyond could be seen.

The sequence instituted a 'clock'... each half-bound, a 10-sided die was thrown for the Elapsed Time (ET) of the half-bound. When the accumulated ET reached 10, several administrative phases took place, one of them being casualty assessment.

Each time a unit was hit, it received a casualty marker... the marker remained with the unit until the ET reached 10, at which time, the actual effect on the unit was determined:

- 01 to 33 Stand loses one man, regardless of number of casualty figures

34 to 66 Stand loses 1 man for every casualty figure

67 to 100 Stand loses 2 men for every casualty figure

Each infantry stand started out with 5 men, and so a high dice throw during the assessment phase could decimate a stand.

I should note that the 20mm figures were each mounted on washers, and placed on a 2-inch by 2-inch magnetic base. Thus, when the stand took casualties, the men were simply plucked off the base and popped back in the box.

Damage to armor was essentially treated in the same fashion. When hit, the armor token (tank) received a marker (smoke puff) which, until its effect was assessed, remained with the tank. At that time, each puff could contribute either 25%, or 30% or 35% towards the destruction of the tank. If, for example, a tank had 2 markers on it, and each was determined to be valued at 30 percent, there was a 60 percent chance that the tank would be destroyed.

And even if the tank escaped destruction, not all the markers would be removed... one marker was kept for the next bound as a residue.

Another procedure I tried was that of "coordinative fire".. Each side had about 5 or 6 officers on the field. An officer could coordinate the fire of two different battalions, if:

- (a) He could see the target

(b) He could see both firing units

(c) Both units hit the target

If (a), (b), and (c) were satisfied, then the target received 2 additional hits. Note that this procedure greatly enhanced the fire power of the concerned units... this gave the officers a definite role in the battle, and it also made their presence quite valuable. During the administrative phase (when the ET of the clock cycle totaled 10), one of the options each side was given was to snipe at the enemy officers.

It turned out that "coordinative fire" was one of the most abused ploys of the game. My original thought was that if there were two units, situated in adjacent areas, and an officer accompanied one of them, then the two units, in concentrating fire, could produce the additional casualty rate.

However, early in the game, the question was raised: why did the officer have to be in one of the areas occupied by the units... after all, weapons could fire for a range of 3 areas, hence line-of-sight was obviously 3 areas.

As long as the officer was 'nearby', and could see the target, then he could coordinate fire. This gave rise to an officer way, way out there, and two units way, way, way over there, who could all "talk" to one another... it appeared that by not specifying exactly, and in writing, the limitations on the "coordinating fire" parameters, the routine went haywire.

General Yama's Highly Imperial Japanese Forces were jointly commanded by Brian Dewitt and Fred Haub. Jim Butters was placed in charge of the defending Marines. Jim had situated his troops in secret... he had a list of the areas (each area had an identifying number) which were beach-side, and he assigned his beach defenses accordingly.

I previously noted that there were some 50 areas on the field, 25 on the beach-side, and 25 inland. The Marine units on the inland-side were openly placed in their respective defensive positions, while Jim's beach-side units remained hidden until (a) they fired, or (b) one of the attacking Japanese units bumped into them (entered their area).

As I remember, the initial landing force consisted of 3 tank battalions (each of 2 stands) plus 2 infantry battalions (2 stands each).

Two of Jim's defending Marine infantry battalions opened up on a Japanese infantry battalion, caused it to take a reaction check, and the result was that the Highly Imperial infantry, inundated with casualty markers, ran back one area to the beach.

In the firing procedures, each firing unit was given a number of Fire Points (FP) for its type of weapon. Anti-tank gun stands, for example, had an FP of 8, tanks had an FP of 6, while an infantry stand had an FP equal to the number of figures on the stand (initially 5 men).

When Jim's Marines fired, each stand in the 2-stand battalion had 5 men, hence the battalion FP was 10 points. Then, because they were supported by a machine gun, an additional 4 points were added, giving a total of 14 FP.

Now, what to do with the FP total? It was multiplied by a Range/Cover Modifier (RCM). The RCM for all units started out as a basic 8, and went down by 1 point for such items as

- (a) Each area fired through. Here, the Marines fired at the Japanese one area away, hence the reduction was -1.

(b) Firing through a covered area. Here the targeted Japanese were in the woods, so another -1 was taken off the RCM.

The resultant RCM was 8-2, or 6, and to get a Probability Of Hit (POH), we multiplied the FP by the RCM... in this case, it was 14x6, or an 84 percent chance to hit. It was hard to miss. Both of Jim's Marine battalions hit the target infantry, each firing unit placing a casualty marker on the unit.

But wait... there's more! Jim had had an officer coordinate fire on the Japanese unit... and since both units hit their target, the target received an additional 2 hit markers, making 4 in all.

The Japanese infantry now took a reaction test to see if they could stand up to this sudden deluge of bullets. The basic reaction factor for all units was 70 percent, and from this was deducted -5 points for every hit on the unit. In this first instance, with 4 hits, the reaction factor was down to 70-(4x5), or 50 percent. The Japanese unit couldn't hack it, and they ran back, taking yet another casualty marker making 5 in all.

Jim's previously-placed defensive forces behaved admirably... they popped up and took a huge toll of the landing battalions. In particular, one of his anti-tank (A/T) gun battalions, composed of 2 stands, kept plonking away at the advancing tanks, and despite the A/T guns absorbing several hits themselves, they refused to fall back.

In retrospect, in the second edition, I shall do away with A/T battalions... I will permit an infantry battalion to be reinforced by a single A/T gun stand, but to permit separate A/T battalions is too much. For example, the A/T FP per stand was 8... hence the total FP for the battalion was 16.

When firing at a tank battalion at a range of 2 areas, the RCM of 8 was reduced by 2 for the range, and another -1 for firing through a covered area, making a total RCM of 5.

This gave the A/T battalion a POH of 16x5, or 80 percent. Too high, too powerful for firing at medium range.

General Yama's Japanese forces had a bad day on the beaches of Wampus Island. The defending Marines prevented them from even reaching the inland-side of the map, and they were kept to the beach-side. Since the victory conditions were defined as the capture of several key areas on the inland-side, the Japanese had no chance at all.

Only one Japanese unit, an all-powerful A/T battalion, attained the high-water-mark of entering an area on the inland-side, and they were quickly driven back (this brought up the question of how in the world a single A/T battalion could achieve a 'breakthrough' when the tanks, which it was supporting, couldn't?).

The sequence permitted the Active Side to move, and this was followed by the Non-Active Side's fire. Then the Active side had a chance to return fire. What both sides waited for was the end of the clock cycle. At this time, several administrative functions took place.

- (a) First casualties were assessed. The casualty markers that the units had received were translated into actual losses.

(b) Then, each side diced for "Special Actions" (SA). There were a host of these.

- (1) You could dice for a reserve stand to come on board

(2) You could dice for a number of infantry to fill out depleted battalions

(3) You could select an airstrike

(4) You could recruit a number of officers

(5) You could snipe at the enemy officers

(6) You could remove damage markers from tanks and A/T units

In short, there were no end of SA's available, and the limitation was that the sides diced for the number of permitted SA's, with 3 being the maximum number. In fact, there were so many selections available, it became confusing for the players to choose amongst 'em. It was suggested that, for Edition #2, the number of options for the Special Actions be reduced. And so it shall be. I certainly don't want the gamers at my table to be confused... clearness and logicality are the byword.

Back to PW Review November 1999 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com