Background

This was a table-top re-creation of a little known encounter between the British and the Americans in the year 1781. That same year, indeed, that same month, the Guilford Courthouse battle was fought, and the CNN reporting staff chose to play up and feature Guilford Courthouse, while completely ignoring the one at Quillford, which took place just down the road. Ardent and intensive research in the archives at the Centre for Provocative Wargaming Analysis has revealed that Quillford was even more important in determining the outcome of the revolution than was Guilford.

More background. Sometime in 1984, the Seven Years War (SYW) rules titled POUR LE MERITE (PLM) were generated. These met with instant acclaim and applause from the three people present in my rec-room (me amongst 'em), as a result of which the rules were never really overhauled in the ensuing 13 years. In short, they seemed to work. A couple of years ago, Scott Holder took PLM, and he and his Virginia-based group modified it to their liking. And Scott recently wrote that Arty Conliffe was interested in Scott's version of PLM, but I don't believe that it will go anywhere... Simon's silly rules systems are too much on the 'gamey' side, ignoring as many historical precepts as possible, whilst focusing on the Milton-Bradley aspects of presenting an enjoyable entertainment. They'll never sell.

But it's now 1997, and even if PLM ain't broken, then, to my mind, it's time to fix it. And so the first cut at a new POUR LE MERITE looked at the American Revolutionary War (ARW). My thought was that if the procedures work for the ARW, they'll work, with few changes, for the SYW.

Under the PLM concept, you don't really need a lot of figures on the field... instead of individual figures being removed from the battlefield, unit efficiency is tracked, and when the efficiency goes below a certain threshold, the entire unit breaks and is removed from the field.

Forces

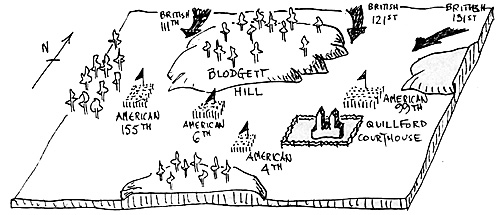

On the Quillford Courthouse battlefield, just as at Guilford, the Americans awaited the British as shown in the sketch. There were 4 defending American regiments, each consisting of 3 companies.. Against them were 3 British regiments, each of 4 companies.

As previously indicated, I didn't use a lot of men on the table-top. All American companies had four figures (men) in them, the British had 5. As the battle progressed, units could be reinforced... the allowed-maximum number of men per company was 6.

If we assume 100 'real men' per company, then the American force, with 12 companies, had 1,200 men in it, as did the British... a fairly small-sized battle.

The sequence was slightly off-beat. Each side alternately drew from a deck of 5 cards, each of which indicated the number of regiments that could maneuver, either 1, 2 or 3. If contact was made, the melee was fought immediately. After every two sequence card draws, there was a fire phase, followed by rally and reinforcement phases.

For the fire phase, a deck of 10 cards was used... each card was annotated with directions such as "2 units of the active side may fire", or "1 unit of the non-active side may fire", "Simultaneous fire by 1 unit on each side", and so on. Two of the cards stated "End of fire phase", and when one of these was drawn, the deck was set aside, and the melee phase began. The card draws meant that it was impossible to predict how long the fire phase would last, or how many units would get to fire.

PLM is what I term a "morale game"... and so was this. When a unit fired, for example, the firing player did not toss the dice to see the effect on the target. Instead, he merely designated the target unit, and the target took a morale test.

If the target was in the open, each man firing would deduct 3 points from the Morale Level (ML) of the target. This deduction was termed the 'fire effect'. All units started out with an ML of 80 percent, and this was modified:

- a. First, deduct the 'fire effect' of the firing unit

b. Second, deduct the distance of the target company from its regimental officer

c. Third, if a British unit was testing, add +5 to the ML

Thus, if an American company of 4 men fired on a British unit, we'd have:

- a. The 'fire effect' of the American company would be (3 points x 4 men) or -12. Deducting this from the British basic ML of 80 leaves 68.

b. Since the target is a British unit, we give it +5 for British steadfastness... the 68 now becomes 73.

c. Third, if the targeted British company's regimental officer is 10 inches from his company (remember that he had four companies to look after, and he couldn't be near all of them), we deduct the -10, leaving 63 percent as the resultant ML for the target company.

The target tests at an ML of 63 percent. If it fails, it falls back, it sends one man to a Rally Zone to be brought back on the field at a later time, and the company receives one casualty marker. This very situation occurred in the fire phase of the first game turn, as on the western side of the field, on Blodgett Hill, one company of the American 155th Maryland Regiment fired at the advancing Brits.

Note several items here. First, the 5-man British units fired slightly more effectively (giving the Americans a deduction of 5x3) than did the 4-man American units (giving the Brits a deduction of 4x3). Second, that the Brits had a small positive morale modifier of +5 when testing. Third, it always paid to 'pick on' the company farthest from its regimental officer.

The 155th Maryland did good work throughout the battle. Facing them on Blodgett Hill was the 4-company British 111th Regiment, the Duke of Drexel's Own North Castershire, Lummerly and Hetford Black-And-Buff Foot. Sad to say, I'm afraid the Duke was not pleased with the performance of his 111th that day.

On the first fire phase, the luck of the draw gave the American 155th two consecutive fire cards in a row. The 155th blazed away at the 111th on both draws. This sudden display of defensive firepower evidently surprised the British, and the entire 111th fell back. Lots of failed morale tests.

Each time a company of the 111th failed its test, it sent one man to the Rally Zone, and received a casualty marker. The Rally Zone of each side gathered men during both the firing and melee procedures. At the end of the bound, all men in the zone tested to see if they returned to the field. If they failed, they remained in the zone, awaiting the next testing phase. In a sense, therefore, single figures never 'die' under PLM rules... there's always the chance they'll reappear.

The critical feature of the Rally Zone is not so much the number of men who do rally, but those who do not. At the end of each bound, after the rally phase, is a Victory Point (VP) assessment... a side gets one VP for every man remaining in the opposing Rally Zone, i.e., who failed to rally. It behooves each side, therefore, to get as many men as possible out of the zone. This becomes rather difficult as 'casualties' pile up during the battle. For example, note that if a company fails a morale test, not only does it send one man to the Rally Zone, but it receives one 'casualty marker'. There's a critical 'casualty marker' level...as soon as a unit accumulates 4 markers, the entire unit zips off-field to the Rally Zone. Eventually, it will recover, but in the meantime, it gives VP's to the opponent.

It was on Turn #3 that the first hand-to-hand encounters occurred. While the 111th on Blodgett Hill was getting clobbered, the companies composing the British 121st Regiment attacked the defenders of the Courthouse. Melee is essentially company-on-company, as the attacking side selects his lead unit, which in turn, defines the lead defending unit.

Melee

There are three basic parts to melee resolution:

- a. First, a Melee Deck is used, enabling the opposing units to fire at each other

b. Second, each of the lead units gets to see if it can call on a support unit.

c. Third, combat values are summed... high total is the winner.

Digression. In an alternate-move system, by definition, the active side, Side A, has quite an advantage over the non-active side. The active side moves his troops, and while the non-active player's units remain completely immobile, Side A can 'gang up' on the opposition's units, attacking with odds of 2 or 3 to 1. Side A says "I gotcha!", and swamps the forces of Side B. In fact, this is only the first of two 'gotchas' produced by the alternate move system.

I try to counter this first "gotcha" with the concept of 'support units'... the active side attacks, designates a single lead unit as the nucleus of its attack (no matter how many units actually make contact), and both sides then have an equal opportunity to 'bring in' a support.

A second problem with the alternate move system, again stemming from the fact that the non-active side is immobile, is that Side A can catch B's units in the flank, or perhaps, undeployed, still in column of march. Side B is thus caught flatfooted by the alternate move system. Side B has no opportunity to reply, to deploy, even though one might think that B's unit officer would have enough smarts, as he saw A's units advancing, to ready his unit.

This, too, is a 'gotcha', and my counter to this effect is to employ a pre-combat Melee Deck, use of which assumes that the two units are not yet quite in contact. The cards here will state such things as "Defending unit will fire", or "Attacking unit will test morale", or "Defending unit may deploy and fire", and so on. The cards, therefore, give Side B's unit a chance to meet the attack. One or more cards in the Melee Deck states "Resolve melee", and when this is drawn, the deck is set aside, and the actual calculations to determine the winner of the melee occur. End of digression.

As the 121st entered the Courthouse grounds, we drew from the Melee Deck, and the units traded fire, but all passed the resultant morale tests. It was then time to bring in a support... the support unit itself has to pass a morale test to assist. The lead British company was able to bring up a support, as a nearby company passed its test. Unfortunately for the American defender, its potential support failed its test, and stood idly by as the melee unrolled.

Now we added the participating companies Morale Level, plus appropriate modifiers, to a percentage dice throw... the high total was the winner and drove the lower unit back. The pertinent parameters were:

| Parameter | American | British |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Morale Level (ML) | +80 | +80 |

| 2. Steadfastness | 0 | +5 |

| 3. Cover | +20 | 0 |

| 4. Support Unit | 0 | +20 |

| 5. Impact of Enemy | -25 | -20 |

| 6. Percentage Dice | 51 | 13 |

| 7. Total | 126 | 98 |

Note the fifth item in the above list, Impact Of Enemy. Here, every man in the opposing lead unit contributed 5 percent to reducing the ML of your own unit. Thus the British 5-man company deducted (5% x 5 men) or 25 from the American ML. Similarly, the American company deducted (5% x 4 men) or 20 from the British ML.

The above is, in all respects, the same type of calculation as in the computation of fire effect during the fire phases... each unit's ML is lowered by the presence of opposing units.

Attacks

In this first attack on the Courthouse, the British were driven back, totaling only 98 points to the Americans 126 points. The Brits were irked... to say the least... and one sequence-card draw later, in stormed the 121st again. This time, the companies of the 121st spread out and engaged all American units on the Courthouse grounds. By doing so, and essentially 'pinning in combat' all available American units, there was no opportunity, in any of the melees, for the Americans to call on other units for assistance since all were already in combat. This deprived the Americans of their "+20" for support.

Several percentage dice throws later (one for each melee), and the 121st had cleared the Courthouse. In fact, the entire eastern side of the field was being swept clean by the advancing Brits, in contrast to the goings-on at Blodgett Hill, where the 155th American continued to do bad things to the Duke of Drexel's Fighting 111th.

Eventually, however, even the Fighting 111th recovered its aplomb and fought back in reasonable fashion. The entire American line was pushed back from mid-field to some 18 inches from its baseline.

One of the factors contributing to the American fall-back was the placement of their guns. Two out of three of the guns had been positioned facing Blodgett Hill, and had virtually no opportunity to fire at the enemy. The third gun was placed on the Courthouse grounds, and while it did well, it was finally captured by the British.

Both sides had three gun models, i.e., 3 batteries. I gave each gun a limited supply of ammunition, ranging from 6 shots to 10. On a fire phase, if a fire card stated "2 units can fire", a battery could be chosen as one of the units to fire. At the end of the battle, I noted the guns' data sheets... all three American guns had fired only 4 times, and most of these shots occurred in defense of the Courthouse.

The British guns were much more active, firing half their ammunition supply.

As the battle drew to a close, and the British came forward and the Americans fell back, more Americans than Brits were consigned to their respective Rally Zones. Both Rally Zones were quite crowded, and as the end of each turn approached, it looked like both sides would pick up an appreciable number of Victory Points (VP). Remember that there was, first, a rally phase, and, second, all those who failed to rally provided VP for the opposition.

What was interesting was that more Americans rallied than did the British. It must have had something to do with the elan of the Continental Army. Each man in the Rally Zone had a 70 percent chance to come back on the field. At the end of 4 turns, when the battle ended, the British had picked up 12 VP, resulting from 12 Americans failing to rally, to the Americans 15, i.e., .15 British stalwarts failing to rally.

The Victory Point totals, because they were grouped so closely, were a wash. VP's were not deemed the only critical parameter. What was most important was that the Brits had complete control of Quillford Courthouse. In short, a British victory.

One might say I went a wee bit overboard in these rules... a sequence deck, a fire deck, a melee deck. The reason was that this was a solo gaming effort, and I wanted to take as much of the decision-making processes (how many units fire, how many move, how many engage) out of my hands as possible.

There should be a better balance between the draws of the sequence deck and those of the fire deck. There were some 8 fire phases during the four turns of the battle, and in 2 of them, the first fire-deck card that appeared was an 'End of fire phase' card, indicating that the movement sequence was to be immediately resumed. In 2 of the 6 fire phases that did occur, one card was drawn, permitting two units to fire, when suddenly, the 'End' card showed up, again cutting off the fire sequence.

Back to the design board. I'm definitely not looking for 'historical accuracy'... but I do want balance. Let's face it... any resemblance between history and a game on the ping-pong table is purely coincidental.

Back to PW Review October 1997 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com