LONE WARRIOR is a British publication dedicated to solo wargaming. Admittedly, many of the articles are useless... descriptions of solo campaigns in which the author gives a fruitless and unproductive "historical summary" of what he did: "King Roscoe's army advanced on that of Prince Glimp, and the Glimpanese cavalry retreated..."

So what? We never find out why the Glimps retreated, or what rules variant caused them to fall back... or if the author was so dissatisfied with the retreat rule that he henceforth banned it... But occasionally, LONE WARRIOR (LW) comes up with a jewel.

In thumbing through my old, old issues, I discovered an excellent article by a fella named Bill Orr, published in LW #59, of May, 1985, which spoke to

- ... methods of creating tactical problems which can be fought out on the wargames table, and how to fit them together to simulate an ongoing campaign.

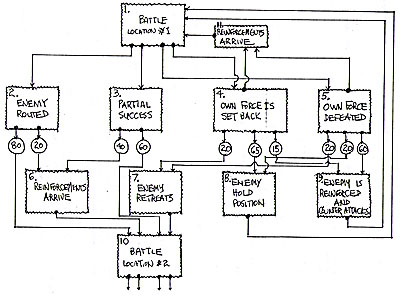

I've reproduced Orr's flow chart of his campaign system, as modified with my own input. The system is not, cross my heart, NOT complicated.

It all starts with Box #1, wherein you set up the first battle of the campaign. The objective is to defeat the enemy at Location #1, and immediately drive forward to counter the enemy at Location #2 (Box #10)... and, perhaps, Location #3, Location #4, etc.

The forces are of your own choosing, although Orr's advice for a solo affair is that the enemy at Location #1 should be about 2/3 of your own strength. Now note that, in the flow chart, there are 4 possible outcomes of the battle in Box #1; these are shown in Boxes 2, 3, 4, and 5.

These outcomes range from completely routing the enemy (Box #2), to getting soundly defeated yourself (Box #5). The definitions of "defeat" and "enemy routed" and "set back", and "partial success", etc., are left up to the campaigner.

The simplest way is to assess, for the battle in Box #1, a series of points... points for casualties inflicted on the enemy, for armor lost, for key geographical objectives taken (or not taken), etc. Compare your point total with that of the enemy's, and decide who did what to whom, and which outcome box... 2, 3, 4,or 5... you fall into.

By way of explanation, let's track our own force which suffers a "set back", Box #4, as the result of the encounter in Box #1. Right now, I don't know the definition of a "set back", other than to know that we did not drive the enemy back, thus clearing Location #1, but we've got to try again.

On the bottom of Box #4, there are 3 outputs, each of which contains a different option for the enemy which just drove us off. Note that the enemy's post-battle actions in Boxes #4, and #5, are indicated by the lines coming out of the bottom of the box; each of these lines has a percentage number associated with it, as follows...

- a. There is a 20 percent chance that the enemy, despite having given us a bloody nose, retreated to Location #2.

b. There is a 65 percent chance that the enemy will hold its position at Location #1.

c. There is a 15 percent chance that the enemy is reinforced, and counter-attacks us.

Where did the 20, 65, and 15 percent figures come from? From my own assessment of the situation, of course. Feel free to set out your own probabilities to reflect what the opposition will do.

Example

As another example, look at the outcomes of Box #2, assuming we smashed the enemy and sent him fleeing. Our initial orders were to get on to Location #2 as soon as possible, hence the outcomes coming out of the bottom of the box indicate that, for us, there's an 80 percent chance we drive right through, without waiting for our own reinforcements to come up. And there's a 20 percent chance that, as we advanced, Headquarters was smart enough to reinforce our troops in a timely manner.

If, at Location #1, we suffered a set back (Box #4), or were soundly defeated (Box #5), the results of these outcomes for us, are indicated by the line emanating from the top of these boxes:

- First, we wend our way back to the battlefield to try again... after all... orders is orders... and

Second, Headquarters gets around to sending us reinforcements before we go in the second time, but

Third, the enemy has its own inherent post-battle reaction, decided by the three percentage figures given at the bottom of the box, hence, if we advance again, it is possible that the enemy won't even be there (having retreated to Location #2), or worse, will be reinforced, and ready to counter-attack.

Note that if we are successful at Location #1 and break through to do battle at Location #2, the entire chart simply "repeats" itself... Location #2 takes the place of Location #1, and there's a brand new Location #3 at the bottom of the next chart.

Maps, therefore, are not really necessary... all you need to know are your destinations, i.e., locations, and, for each location, a significant terrain feature which forms the focus of the battle. For example, for the campaign I generated, I noted the following four locations:

-

Location #1 Gain control of the town of Charsk

Location #2 Drive the enemy from the bridge crossing the River Andros

Location #3 The enemy is dug in on Shorlap Ridge

Location #4 Gain control of the town of Korl

Draw up a map for each location, for if you have to repeat a battle at any given site, you've got to set up the same terrain features for the second encounter.

Spearhead

In late February, our group was invited to Bob Hurst's house for a game using Artie Conliffe's WWII rules, SPEARHEAD.

I decided to use this battle, Germans vs Russians, as the first in the campaign, the battle for the town of Charsk. My comments on the rules should be contained in another article, somewhere in the pages of the REVIEW (most probably not this REVIEW).

Suffice it to say that, having defined the Germans as the attacking force, they were driven back, suffering severe losses under the SPEARHEAD rules. Bob had set out a scenario given in the SPEARHEAD book, in which the Russians outnumbered the Germans. It took only four bounds before it became obvious that the Germans were going nowhere.

The town of Charsk remained in Russian hands. In effect, this was the result defined in Box #5 of the flow chart, a resounding defeat for the German attacking force. A couple of days later, I set up a solo game at my house in which the Germans attacked again.

This time, I didn't use SPEARHEAD - which is definitely not amenable to solo play - but a set of my own.

And this time, the forces were somewhat 'more equal'... the attacking Germans slightly outgunned the defending Russians. Under the Simon rules system, a group of three tank models (stands) represented a tank battalion, and 4 infantry stands (each stand a company) represented an infantry battalion. The Germans were given 5 armor battalions, while the defending Russians were given 4 armor battalions. Each side had 2 infantry battalions. In essence, this was a division-vs-division encounter.

And this time, the Germans were successful. While they didn't rout the Russians as prescribed in Box #2, they ended up in Box #3... a 'partial success'. Using a point system (1 point for an enemy infantry casualty, 3 points for the loss of an enemy armored vehicle, etc.), the results indicated that, after some 6 bounds, although both sides had lost about one third of their original force, the Germans had scored some 15 percent more points than did the Russians... hence the 'partial success'.

Which immediately brings the rating system to mind... is the loss of an armored vehicle to be valued at 3 times that of an infantry figure? Why not 5 times? How about a heavy machine gun? The point system used to define 'enemy routed', or 'partial success', etc., is very much a function of the particular rules used. This is no easy task. I note that in a recent wargaming publication (was it THE COURIER?), the reviewer looked at SPEARHEAD and gave author Artie Conliffe a hard time because he, Conliffe, had failed to place a point rating system in the rules.

Back to the Campaign

Back to the campaign and the flow chart. The next battle took place at the bridge crossing at the River Andros. The decision point here concerned which output on the bottom of Box #3, the 'partial success' box, was appropriate. Note that there is a 40 percent chance the Germans, as the advancing party, get reinforced before they reach the Andros River at Location #2, versus a 60 percent chance the Germans simply drive right on from Charsk, receiving no reinforcements. A low dice throw decided that the advancing Germans got reinforced before they reached the river.

This game was set up just before the HMGS convention, COLD WARS. At my house, to be ferried to the Lancaster, Pennsylvania, convention site, along with two young (relatively speaking) British friends whom I had picked up at Dulles. Tim Stubbins took the part of the attacking German commander, and Tom Elsworth played the defending Russians.

The town of Noburg was situated near the bridge, on the south side of the river, and played a crucial part in the battle, since the Germans had to pass through Noburg to get to the bridge. Tom placed a Russian armor battalion (3 stands) in Noburg Woods, just east of Noburg, and he had one infantry battalion of 4 stands advance over Noburg Hill, just west of Noburg. In effect, therefore, he thus pretty much controlled the area leading to the bridge.

After playing such games as COMMAND DECISION and SPEARHEAD and other WWII rules sets, in which every token on the field could fire on the fire phase, I wanted to promote "volley fire"... all the weapons of one type could fire as an entity, thus drastically curtailing the required number of dice tosses. And so, in the fire phase, for example, when a heavy tank fired, it had a basic 60 percent chance, i.e., probability of hit (POH), to hit the target. Each additional heavy tank firing at the same target added 10 percent to the POH... if three tanks fired, therefore, the total POH became the first tank's basic 60, plus (2 x 10), or 80 percent.

The resultant dice throw could produce a maximum of 2 hits on the target. Hit markers remained on the target, and the effect of these hits became known on the Damage Assessment phase. Here, each hit marker on the target was valued at 25 percent. One first found the total, T, resulting from all the hit markers on the target and then referred to the following table:

-

---------------------------------------------------------------

No effect, markers remain on target

T ---------------------------------------------------------------

Target receives one additional hit marker

1/2 T ---------------------------------------------------------------

Target destroyed

---------------------------------------------------------------

Thus, on the above table, if a target had three hit markers on it , the total, T, was 75 percent, and a percentage dice throw of 37 or below destroyed ft. A throw of 38 to 75 resulted in yet another marker being placed on the target.

During the bound, there were several Damage Assessment phases, and as the markers on a given target accumulated, the chance of its being destroyed on one of these phases became greater.

There was a rally phase during the bound, during which the division commanders could attempt to remove the hit markers on the tanks under their command. The division commander had a basic 70 percent chance to remove all the markers on a given tank. It turned out that the 70 percent figure was too high... hit markers were removed too easily. Another way of saying this is that although the "hit rate" was fine, the actual casualty rate on the field was too low. One would think that, by now, in drafting a set of rules, I could guess at a satisfactory rate of death and destruction, one to keep the game going. Evidently, not so.

But back to the battle at the bridge. Tim's advancing German force took it on the chin from the defending Elsworthian Russians. Around Bound #6, Tim threw in the towel... too many losses. In terms of the campaign, his attacking Germans had suffered a "setback"... Box #4 on the flow chart.

This means that the Germans will have to try again at the bridge. This will be the fourth battle in the campaign... I'm curious to see how many encounters actually occur.

Back to PW Review April 1997 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com