I think Tony Figlia slipped some fishy dice into the game. Ya gotta keep an eye out for these guys.

I commanded the Union right flank ... two divisions of Yankees advancing north on Tonytown, held by Tony's Rebels. My boys were about 24 inches south of Tonytown, heading straight north, and things were looking good, when Tony suddenly announced he had thrown the dice to determine the entry point for two off-board Confederate divisions, and golly-gee-whiz! ... his two divisions appeared on my flank, about 12 inches to the right of my advancing units.

Now doesn't that sound fishy to you? There I was, about to winkle the Confederates out of Tonytown, and suddenly, a huge rescue force appears, and completely diverts my two divisions. Fred Haub commanded the two flanking Southern divisions, and he rapidly deployed them (they had come on the field in column formation) and prepared to do me grievous harm.

But there's more than one way to skin a cat. 'Twas at this exact moment, that in the doorway appeared John Shirey, a latecomer to the game, and I shouted: "Your troops are being flanked, John, come in and toss the dice!"

I was going to leave it to John to find a way out of the predicament. John is a rather savvy player; about the worst one can say of him is that he has a predilection for DBM, DBA, and those other yucky WRG products. But I have an open mind, and I still let him play on my ping-pong table.

And so we resumed the battle. This took place in 15mm, and we used Simon's Distorted American Civil War (SDACW) rules, which employs the following organizational setup:

- 1 stand equals one regiment

5 regiments (5 stands) equals one brigade

From 2 to 4 brigades comprise a division.

A full division, therefore, consists of a maximum of 20 stands, i.e., a total of 20 tokens for a player to push across the field ... plus one artillery stand, plus a command stand.

"Now why are the rules 'distorted'?", you ask. I shall explain forthwith.

First, my 15mm ACW figures are mounted on stands measuring 1-inch-by-l-inch. If we assume that each stand - supposedly a regiment - represents, say, 900 men, in three ranks of 300 each, then the frontage of the stand is composed of 300 men, side by side.

Second, let's give each man a full yard in which to load his musket, tamp the powder and ball, etc. This is a wee bit more generous frontage than that allowed the Napoleonic troops, who were squished into line side-by-side, and each given a distance of 22 inches in which to maneuver.

Third, our stand's worth of 300-men in the ACW line thus has a 300 yard frontage. But 300 yards, say the books, was the effective rifled musket range in the ACW. Which means that the frontage of the stand (1 inch) is a measure of the distance that the stand should fire, i.e., 300 yards.

And that's where the distortion comes in. Instead of keeping to scale and having the musket range defined as 1-inch, I permitted the muskets to fire a distance of 20 inches!!! Egad!! In effect, therefore, as each stand fired, its little leaden mini-balls took off like Scud missiles, hooking over the horizon, and causing great consternation far beyond the scaled range.

What this does, in effect, is to transform a battle in which one speaks of maneuvering brigades and divisions across the field, into a rather large size skirmish encounter between companies, perhaps even squads. Despite the inherent distortion, I still prefer to reference regiments, brigades and divisions rather than companies; it provides a certain amount of gloss to the battle ... it's much more impressive to record: 'The 4th Division moved out', than merely to state, 'Company B advanced on the right flank.'

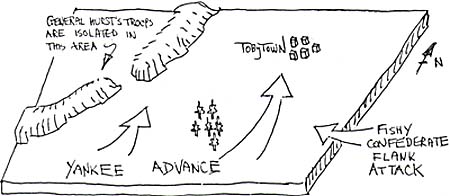

But enough of this folderol ... to the battle. The sketch shows the basic setup. To the west, isolated behind a range of uncrossable ridges, were two Confederate divisions, commanded by Bob Hurst. It was General Hurst's task to break out through the one pass in the ridgeline, and join the rest of the Rebel force.

Each side was given some 15 brigades, grouped into 4 or 5 divisions. The battle, therefore, consisted of a corps-versus-corps encounter.

It is my sad duty to relate that the Union forces lost, and lost badly. John Shirey, to whom I transferred my right flank troops, got whomped (better John than me, was my thought) by Fred Haub. I got slaughtered by Tony 'Slick-Dice' Figlia, and on our Union left flank, even though Confederate General Hurst never broke out from behind his ridgeline, he still delivered enough grief to contribute to the Union defeat.

The sequence was an alternate one. Each half-bound consisted of: (a) the active side moved and/or fired; (b) the non-active side fired defensively, and (c) the active side closed for melee. At the end of each half bound, we added a fourth phase, (d) each side rallied troops.

Toward battle's end, my 15mm division commander, General Thwackett, advanced his troops to Tonytown on their movement phase. Then, before they closed for hand-to-hand combat, the defending Rebs got their defensive fire. Tony's Confederates were permitted 2 volleys; the firing routine was as follows:

- a. Each firing stand received one Hit Die, a 10-sided die, on which a toss of 1, 2, or 3 registered a hit on the target. A 5-stand brigade thus tossed 5 dice. Each artillery stand was defined to fire with the effect of 4-stands, hence normally threw 4 dice (2 more were tossed in for close-range canister).

b. Each hit on the target unit resulted in a marker placed on the unit. Three such markers and one stand was removed, taken off the field and placed in the Rally Zone.

c. The target unit, if hit, immediately took a morale test. If the unit failed, it received another marker. Note that this additional marker could result in a stand taken off the field if the unit hit the 3-marker threshold.

General Thwackett's men were hit hard by Tony's defensive fire; a profusion of markers caused several stands to disappear, but the Thwackites stood firm during the morale test.

They charged in. BANG! WHOMP! BAMMO! They fell back. No contest.

In the melee, each stand received a Hit Die, just as in the firing procedures. And, just as in firing, a toss of 1, 2, or 3 produced a marker on the enemy. For every 3 markers placed on the enemy, one stand went off to the Rally Zone, and the winner of the melee was determined by the following 3 parameters

| S N D |

The number of your own surviving stands The number of markers you placed on the enemy A random 10-sided die roll |

These 3 parameters were combined into a Melee Result, and the winner was the side with the higher Melee Result:

- Melee Result = D x (S + N)

I indicated above that each stand received a Hit Die; other Hit Dice were available. For example, the defending Confederate troops received another 2 dice for the cover factor of the town. Another source of Hit Dice was the division commander, himself. Each division commander was given a total of 8 Hit Dice for the entire battle with which to help out any of his units in melee. Once used, his dice were gone forever. As I remember, General Thwackett tossed in 4 of his available 8 dice ... he could have saved them for all the good they did.

Digression. I've mentioned above that the firing and melee systems are quite similar. Familiarity with one, therefore, gives a familiarity with the other. There's no need to study two dissimilar sets of procedures.

I have always wondered why rules authors (not all, but a great many) present one system for firing and another, totally different, for combat. Both procedures deal with the determination of an impact on a force, an impact which is affected by factors for cover, for type of weapon, for armor, for size of unit, etc.

My feeling is the authors don't give enough thought to the systems they're generating. They tend to focus on the nitty-gritty of the situation, instead of the actual procedure. Hence the predominance of charts ... one containing 23 factors for the firing unit to consider, another with 20 factors for the target unit to compute, perhaps a third chart (with only 15 factors) applicable to both sides, etc. The focus is on 'precision', and there's little thought as to whether or not greater 'precision' results in greater 'accuracy'.

I have to admit that Simon-type-rules consider neither precision nor accuracy. They zero in on what might be termed 'effect' . You toss the dice, I toss the dice, we both throw in an applicable factor or so, and we both inflict "casualties" on each other's troops. I have always maintained - I shall always maintain - the position that setting up a miniatures game on a ping pong table and tossing 6- or 10-sided dice to decide the outcome, can, in no way, result in a true battle simulation. What one sets up is a "game", pure and simple.

Given this viewpoint, there's no need for 'precision', and there's very little need for 'accuracy' , as long as what emerges has the desired effect. He who disagrees with this rather simplistic view of table-top wargaming may address a letter to the editor. End of digression.

Back to the battle. Having been beaten back, the half-bound was over, and we entered the rally phase. During this rally phase, each side performed 2 tasks:

- First, the side tried to bring the troops in the Rally Zone back to the field. One 10-sided die was tossed for each stand:

| A toss of 1, 2, 3 A toss of 4, 5, 6 A toss of 7, 8, 9, 10 |

The stand rallies The stand dies The stand remains in the rally zone. |

Second, the side tried to remove markers on the units in the field. Each division commander had a 'rally capability' (diced for prior to the battle); Thwackett's was 70%, which meant that he had a 70 percent chance of removing one marker from any of his units. He could then attempt to remove a second marker at 10 percent less, i.e., 60%, and so on. Each time he failed, however, the unit in question received another marker. Note that if a unit already had 2 markers, and the General failed, a third marker would appear, and off would go the stand to the Rally Zone.

It was during the dice tosses on the above rally chart that we Unionists were truly smitten. A preponderance of 4's, 5's and 6's showed up. Our units never recovered.

My division, that of General Thwackett's, suddenly broke. Thwackett had initially been assigned a Victory Point Threshold (VPT) . Thwackett's VPT had been calculated as the sum of: 2 points for every brigade in his division plus another 2 points for good luck.

Thwackett had 3 brigades - this gave him 6 points - and the additional 2 points gave him a total VPT of 8. A general's VPT never went up, it only went down. If a unit failed a morale test, the VPT was reduced by 1; if a unit lost a melee, it was reduced by 3. When the VPT reached half value, bad things happened.

Somewhere around the 5th Bound, Thwackett's VPT went down to 4, the halfway level, which was critical; this was 'bad thing' time. At this halfway point, there was a 50 percent chance that one of Thwackett's brigades would leave the field. I tossed the dice ... no surprise here ... one brigade fled.

Each time one of Thwackett's units received any additional markers, his brigades had to take the dreaded 50 percent test. Alas! ... one by one, each of Thwackett's brigades fled the field. Soon, there was no one left but Thwackett himself ... I could see the General standing alone, crying little 15mm tears, staining his hand-painted jacket. Pitiful, pitiful.

Bound 5 broke the Union forces. John Shirey's division on our right flank had been decimated by Fred Haub, my own division (Thwackett's) in the center of the field was no more, and that was that.

I instituted the VPT test to ensure that a battle would come to a definite end. I've seen too many rules sets under which an encounter grinds on and on and on. While the VPT procedures do not define a specific set of victory conditions, they do prevent a 'fight-to-the-last-man'. The breakup of the divisions on the field, as the individual brigades flee, simply reduces one side or the other to the point at which it cannot fight on.

One additional gaming ploy which was tested involved the use of a deck of 15 cards. Each half-bound, each side drew one of the cards. Three of the 15 indicated "No effect", while the other 12 noted such items as "Designate one enemy unit to fall back", or "Receive one additional artillery volley", or "Opposing side forfeits its rally phase".

I've tried "chance cards" in a number of games and designing a deck of these cards is a tricky business. The cards can't affect the outcome of the game too much because (a) the presence of too great a random factor takes control of the game away from the participants, and (b) those at table-side will approach the author and pummel him, verbally and otherwise. On the other hand, if the effect of the cards is too small, and their impact is of no consequence, why include them at all?

The ideal chance card deck provides a minor irritant; while it will slow up a side, it should not prove completely debilitating. During the battle, we Unionites picked the same card twice in a row: "One enemy brigade will fall back", it said. John Shirey applied the card to Fred Haub's advancing flanking force. while it took the smile from Fred's face, it only made him meaner, giving him greater joy as he destroyed all of John's brigades.

Back to PW Review June 1996 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com