It was early in the morning of April 19, 1775, that Paul Revere took off, shouting "One if by land!", alerting the countryside, awakening his neighbors, and, in general, annoying everybody.

Yes, the British were coming out of Boston, aiming first for Lexington and then Concord, where the troublemakers had stashed their ammunition and artillery... and that was the scenario I set out on the table... almost.

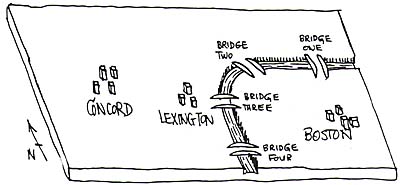

The map shows the British located in Boston, ready to move out. They have a choice of four bridges to cross as they proceed to the west, and at each bridge, in anticipation of the forthcoming encounter, stands a band of Minutemen.

In truth, the history books don't show any such bridges, but they probably should. There was one bridge at Concord, the "rude bridge that arched the flood", where the whole thing started, but I purposely left this one out. There's no sense in getting too historically accurate... it opens you up to criticism.

And so, in my version of the episode, the Minutemen, instead of waiting to gather until the Brits had reached Concord, gathered that much earlier. But with a slight difference.

Each group of Minutemen, termed a company, was defined to be in disorder... they couldn't move, they couldn't fire, they couldn't change formation, they couldn't exchange Easter cards ... they could do nothing until they rallied.

Which meant that if the advancing Brits could hit 'em before they got their act together, they'd automatically fall back, in even worse disorder than before. Two such hits would eliminate a minuteman company.

This gave the British commander two options... (a) he could ignore the Minutemen near Boston, and charge straight ahead with all his forces for Concord, or (b) he could divert several of his units to chase down the as-yet-unformed Minutemen to eliminate them. This second option would, of course, result in fewer units to oppose him on his return trip to Boston.

Digression... in my intensive research effort prior to setting up the battle (and does anyone out there doubt the existence of such research??), I noted in the paintings and sketches and lithographs and other miscellaneous illustrations of the April encounter, that all the Americans (or Muricans, as we are wont to say) have their tricornes on and are dressed either in (a) a light top coat, or (b) their shirtsleeves.

Now, here in the Washington, DC, area, April mornings are chilly, chilly, freezing affairs. Many are the times that I have waited on the bus stop at about 0600 in the morning, shivering despite my collection of scarves and mufflers and gloves and mukluks, etc.

And so I must assume that an April morning in Massachusetts is no bargain either. Thus when I see a sketch of a Minuteman at Lexington and Concord clad only in his shirtsleeves potting at the British, I tell myself... thees ees one tough hombre, Senor; thees ees a man who can ignore the cold and the fact that his fingernails turned blue about an hour ago, and keep shouting "Murica for the Muricans!"... and the British obviously picked on the wrong group of guys.

End of digression.

The figures we used were about 40mm in size, all single mounted. About a decade ago, Paul Koch gave me a set of the miniatures; they had been manufactured in Hong Kong, and were made of hard plastic, which takes paint very well.

What was most interesting about the figures was that they were 40mm clones of the 20mm Airfix line. All of the Airfix line are beautifully sculpted, and some artist in Hong Kong had crafted excellent reproductions of the Airfix American Revolution figures, somehow doubling their size.

I started with about 30 figures, made my own variations, put a couple in a mold, and have turned out a respectably-sized collection. My own clones, the Simon variations-on-a-theme, are in no-way works of art; they are faceless li'l fellers, somewhat overweight, but they fight just as fiercely as any in my collection.

The game was played at "company" level ... I termed each group of men a "company"; three companies comprised a battalion, two or three battalions a brigade, and a couple of brigades made up a division.

company size varied according to the type of unit. British regulars had 6 men (figures) in a company, Murican regulars had 5, and the tories and militia groups had either 3 or 4.

Each company had its own data sheet on which were listed 10 to 12 numbers, starting out at about 80 or 85, and ending up down around 40. These numbers represented the morale level of the company; as the unit took losses and its numbers were crossed out, the morale level dropped lower and lower.

It was way back in '84, that we first came up with our "morale game" rules, which eventually developed into POUR LE MERITE (PLM), a set for the Seven Years War. This is the rules-set described by Scott Holder in the latest COURIER.

For this battle, however, we reverted to the original scheme, and greatly simplified the system. As I go through the battle description, I'll highlight the procedures of interest.

Fred Haub commanded the British troops; Jeff Wiltrout arrived later to help him out. Bob Hurst, ably assisted by one W Simon, ran the Muricans.

We, the Hurst/Simon staff, had three brigade commanders on the field... all of them had their work cut out.

At the outset, we Muricans were somewhat disadvantaged. Of the 15 companies on our side, 12 were initially "disordered"; before they could take off down the field, they had to pass what we termed a "stress morale" test. And before they could even take the test, the brigade commander had to run up to them and bless them.

On each company's data sheet was listed its current Morale Level (ML). There were about ten numbers for a company, ranging from a high of about 80 to a low of 40. Each time a casualty occurred, an ML number, i.e., a "box", was crossed off.

For the Murican 94th Militia, for example, its initial ML was listed as 88. "Stress morale" was defined as half the current ML. This meant that to get started, the 94th had to pass a stress morale test at a level of 44% (toss percentage dice lower than 44) in order to form up and move out.

And, as I indicated, before the 94th could take its test, its brigade commander, Major O'Toole, had to dash up to the company and utter a benediction. The officers moved at 15 inches per bound, and Major O'Toole was a busy man, indeed.

O'Toole was rather lucky; he managed to rally four of the six companies in his battalion. Major Simms, another Murican brigade commander, who was situated near Concord, was in such a hurry to bring his troops forward that he left behind a unit or two... he never had time to reach them to permit them to attempt their stress morale test.

On the Murican side, in retrospect, our tactics were wrong... we rushed up to meet the British, instead of taking our time to organize our units and form some sort of defensive line in front of Concord.

One Murican unit that we must mention in dispatches is the 94th Militia. Stationed on Bridge Two, this 4-man unit, heroes of the revolution, traded shot for shot with the incoming British, driving them back, and then repulsed a Redcoat assault, before being forced to fall back to prevent themselves from being surrounded.

Each time the 94th was successful in beating back the Brits, I placed a red-coated prone casualty figure to mark the spot; Jeff Wiltrout, who appeared around Turn #4 and assisted in moving Fred's troops, seemed to think that for every British casualty inflicted, I set out some three casualty figures, but placed only one when the muricans were injured. I plead guilty as charged... I admit there was a pile of British casualty figures near Bridge Two, but I attributed this to the good work done by the 94th.

When the 94th traded fire with the oncoming Brits, the procedures went according to the format below.

Each turn, after the active side finished moving his troops, a fire phase followed. Each side was given a Volley Deck of 6 cards, on each of which was annotated something like: "One company can fire" or "Three companies can fire", and so on.

Each side tossed percentage dice and determined if it would contribute 2, 3, or 4 Volley Deck cards to be placed in a common Fire Deck. The Fire Deck cards,were then drawn at random, and the sides chose the appropriate units to fire. The number of Fire Deck cards could thus vary from a total of 4 to 8. Also inserted in the Fire Deck was an "End of Fire Phase" card, which, when drawn, stopped all firing immediately. All Fire cards were then returned to the sides, ready for the next turn's fire phase.

When the 94th was selected to fire, each of its 4 men contributed 3 points to reduce the Morale Level (ML) of the target unit. Thus when the unit fired at the 67th British Line, which had a ML of 86, the 86 was reduced by 12 points to 74.

The ML of 74 was further reduced by the distance to the 67th's brigade officer, say, 6 inches. This brought the final ML of the 67th to 68%.

The 68% figure could be increased by allocating a series of 10 percent augmentation factors intrinsic to each battalion. Most of the time, the players used these augmentation factors to increase the ML of the concerned unit to around 80%, thinking that 80 percent was an attainable goal.

I noted that no one used the "Elsworth Theory of Augmentation", which is to always contribute enough points to bring the unit up to a level of 100%. "If you've got 'em, use 'em", says Professor Elsworth.

The melee procedure worked in pretty much the same way. Each side took a morale test and a chart similar to the one below was referenced:

-

-------------------------------------------

One man to the Rally Zone

Cross out 2 ML boxes

ML -------------------------------------------

One man to the Rally Zone

Cross out 1 ML box

1/2 ML -------------------------------------------

No effect

-------------------------------------------

Thus if a unit had an ML of 76, a toss of 38 or under produced no effect, while a toss of over 76 resulted in men being removed (temporarily) and 2 ML levels being crossed out on the data sheet.

Which side won the melee was decided by a comparison of the number of remaining men, and the casualties inflicted on the opposition.

At the end of the active side's movement phase, after all melees had been resolved, the active side could then rally those men placed in the Rally Zone from the fire and melee procedures. This meant that men were continuously "recycled" from the Rally Zone to the field and back again... no individual figures ever "died".

Rather than single figures, whole units, i.e., companies, died... a unit was deemed destroyed when all of its ML boxes on its data sheet were crossed out. Each unit had some 10 boxes, hence it took about 10 hits before the entire unit (company) went up in smoke.

Under this set of rules, "recycling" was necessary because of the relatively small size of the units. Regular army units had a maximum of 6 men in them, and militia had a maximum of 4. on the field, many companies didn't even attain these levels.

If, in a 3- or 4-man unit, the men were removed permanently when the unit took casualties, it would be short game, indeed. Use of the Rally Zone, and of the data sheets, permitted a more flexible use of available figures, with no need to field large units of, say, 12 or more figures.

The result is that with the prevalence of small units on the field, the game resembles a huge skirmish affair, with 4- or 6-mann companies dominating the playing area.

We played some 7 or 8 turns in the battle, when it became obvious that the British forces were simply not going to be held up by the Muricans. Concord was doomed.

Of an initial 15 companies on the Murican side, only 8 were left, and several of the remaining units had most of their ML boxes crossed out.

This meant that even if we pulled back, and let the British enter Concord, and then proceeded to pot them on the way back to Boston, we'd still lose out, so depleted were our ranks.

Bob Hurst and I threw in the towel, thinking that we'd return to fight for freedom on another day, with of course - another set of rules.

A final thought on the rules.

On the field, the only officer figures required by the rules were the brigade commanders, such as Major O'Toole. The reason for the need to represent them was that they served as a reference point when one of their units took a morale test (the unit subtracted the distance to the brigade commander from its ML).

As the battle developed, O'Toole was wanted in quite a few places at once, and unfortunately, he couldn't be everywhere at the same time. This held true for all the brigade commanders as their units came under fire.

Using the distance to the officer as a reference is, in essence, similar to the procedures that set out a magical, mystical aura for officers. The magical, mystical aura is defined by the rules set as the circular area covered by a radius, say, of 12 inches, centered at the officer... all units within the area will instantaneously hear, understand, and obey the officer's orders... units outside the area are deaf, dumb and blind, and have to be prompted to perform their duties, and even then, they may not function properly.

Using the actual distance to the officer seems to me to be a wee bit more - dare I say it?? - realistic. In effect, as the distance to the officer increases, the impact he has on his units decreases proportionately; there is no abrupt cut-off, wherein ' on one side of the line, all units perform perfectly, and a few yards off, on the other side of the line, we have a number of dysfunctional men who need psychiatric help.

Back to PW Review January 1996 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com