History in a nutshell (I must note that I know as much about history as I do about astrophysics and sub-molecular fusion engineering, but if I start off with an historical background, it gives the entire article a certain aura of legitimacy). Anyway, the time is 48 BC and the triumvirate of Caesar, Pompey and Crassus is no more... Crassus died in 53 BC, and civil war had broken out between Caesar and Pompey.

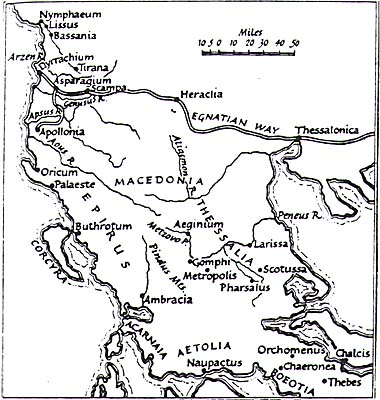

Caesar drove Pompey out of Italy, followed it up by destroying Pompey's forces in Spain, and went after Pompey himself in Northern Greece. At first, Caesar couldn't make any headway against Pompey. He had fewer infantry and cavalry, and the battles went back and forth. Finally, Pompey set up near Pharsalus, and that's where we step in.

Pompey had some 45,000 troops, plus another 6,700 in cavalry. Against them, Caesar pitted 22,000 men and about 1,000 horsemen. Pompey placed his entire cavalry force on his left wing; he knew his horsemen outnumbered Caesar's, and his thought was to smash into Caesar's right flank, and roll up the rest of the line.

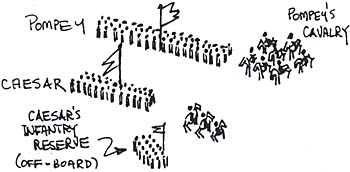

But Uncle Julius, seeing that all the enemy cavalry was grouping on his right flank, took some 3,000 men out of his front line and placed them on that flank. Caesar's force of 3,000 was unnoticed by his opponent; they were stationed slightly back and out of sight, shielded by his own mounted troopers.

Pompey's cavalry charged and threw back Caesar's horse, whereupon forward came the hidden 3,000 man reserve, and routed the Pompeyan cavalry. This, in turn, left Pompey's own left flank exposed, and that was that... Pompey was no more.

In the table top encounter, to account for the salient characteristics of the battle, I did the following:

| a. | Pompey was given about 12 units of infantry, and some 4 units of cavalry. Caesar was assigned about 9 units of infantry, and only one of cavalry. |

| b. | Of Caesax's 9 infantry units, 2 were initially placed off-board. When the appropriate time came... after the Pompeyan cavalry charge... they would suddenly appear on Caesar's right flank, and we hoped, would eat up Pompey's cavalry. |

| c. | Lacking 2 units from his force, this, of course, left Caesar with a relatively short front line, permitting Pompey to extend both of his flanks. |

| d. | Caesar's troops, although inferior in number, weref according to the histories, superior in fighting qualities than their opponents. Accordingly, all of Caesar's infantry were heavy units, while only one of Pompey's 12 units was heavy... the others were medium infantry. |

The sketch below shows initial dispositions:

Bill Rankin and I ran Caesar's forces; opposing us were Tony Figlia and Bob Hurst. Bob took the part of Labienus, who headed Pompey's left flank, the cavalry-heavy one that was supposed to roll up Caesar's army.

Bob was unaware, of course, of my hidden, off-board reserve, and I warned young Bobius Labienus Hurstius that I had read the omens and that dire things were about to happen to him... he ignored me.

Oh, well, I would give Bobius Labienus Hurstius a fine Viking funeral when the proper time came.

The Figlia/Hurst forces immediately came forward; there was no reason for them to hang back... they outnumbered the Rankin/Simon troops. The rules sequence for the half-bound has, essentially, four basic phases:

| 1. | Side A, the active side, moves his troops forward. His units cannot approach any enemy unit closer than 3 inches until the melee phase begins. |

| 2. | Side B's missile troops fire, and all those units of Side A's which are hit, will take a morale test. |

| 3. | Side A's units which are 3 inches from those of Side B's, may close to contact; melee is resolved. |

| 4. | This is a rally phase, in which both sides participate to reorder and rally troops. |

Phase 1 permits Side A to do a wee bit more than simply push his troops up the table.. His light missile units get a chance to fire during his move forward. On his movement phase, Side A does the following:

| 1a. | Side A dices to see if any units get an "additional" move, even before the entire force advances. Each force is divided into wings, groups of 2 to 4 units each, and in each wing, there may be one or two units permitted this additional move. |

| 1b. | Side A now looks at all of his missile firing units, both foot and horse. Each such unit has a 50% chance to advance 10 inches, fire, and pull back 10 inches. |

| 1c. | After his missile troops fire, Side A moves the rest of his force forward. |

Digression. I have to admit that I have no idea of how to treat light troops in an ancients battle. They're supposed to be rather "fluid" in their movement, but most rules take this into account simply by giving them a larger movement distance than the other types of infantry... they're still confined to moving along with the rest of the army.

Their "fluidity" is also supposed to show up in their combat tactics... they won't stand up to heavier units, but will, when advanced upon, evade combat. Some rules permit them to dash back out of harm's way. Other approaches - such as that in ARMATI - are slightly more devastating... an advancing heavy unit simply "eats up" any light unit it touches... POOF!, and they're gone... serves 'em right for getting in the way.

And in yet other sets, the light troops will fight when contacted; they'll fight at a much lesser strength than their opponents, but fight they will.

What I did in the la, 1b, and 1c listings of Phase 1 above, was to give the lights a heck of a lot of "in-phase" flexibility. First, on Phase la, they can be chosen as one of the units given an additional move. Second, on Phase 1b, they can jump ahead yet another 10 inches, fire, and fall back to their lines.

Third, on Phase 1c, they move with the rest of the army. In short, the lights can be all over the place.

I did mandate that when a heavy unit contacted a light, the heavy would go right through, brushing the light unit aside, forcing them to evade. Here, the light unit would take a casualty marker, but out of spite, as they fell back, they'd take a shot at the oncoming heavies. But I fell far short of the ARMATI "death to the lights" approach.

Is all the above truly representative of what light troops did those many years ago?? All I can say is that it makes for a more interesting game. End of digression.

As Pompey's troops moved toward ours on their movement phase, out came their lights and peppered away at us. Several of our units received casualty markers but they didn't hurt... yet. When light missile troops fire during their own movement phase, as described above, that's defined as "harassing fire"... no morale test required. It's only on the non-active side's fire phase that targeted units must take a morale test.

Firing is simply accomplished by tossing a number of 10-sided dice (Hit Dice, HD). Tosses of 1, 2 or 3 produce a hit. Each firing unit receives 4 HD, and an HD is taken away f or "target in cover", "target is armored", etc. It's much, much easier to deal with whole numbers of dice rather than with modifiers to the die roll itself.

The rules rely heavily on two types of markers:

| a. | Mounted courier figures. I scrounged up every spare 25mm ancients-type mounted figure on my shelves to form a "courier corps", all single mounted. Consequently, I have Thracian couriers and Babylonian couriers and Greek couriers and Palmyrian couriers and Byzantine couriers and Assyrian couriers... you name 'em, they're all there.

At the outset of the battle, each wing commander is given a staff of couple of couriers, and the force commander is given a few more. Now if you're a purist, and it offends your very being to see Assyrian couriers run around the field in a battle between Roman forces, I can't help you ... in fact, I refuse to help you. I can only note that that's the price you pay if you want to play a game on my table-top. The couriers help out in morale tests, rallying, removing hit markers, etc. Each time a courier assists, his figure is removed from play, and because there's a limited supply of couriers, one has to prioritize their use. | ||

| b. | The other marker is a casualty figure. Sometime ago, I took a 25mm mounted trooper, an ancients-type of fellow, and sorta pounded the bejeezis out of him, flattening him sufficiently so that he'd lie down, rather inertly, yet gracefully, on the table. I then took the poor fella's limp body, popped him in a mold, and have turned out ancient casualty figures ever since.

Each time a unit incurs a hit, one casualty figure is placed beside it. As indicated in Paragraph a, above, these casualty figures can be removed by using the couriers. As an example, there's a "rally phase" at the end of each half-bound, during which a side can take a courier from headquarters and, using percentage dice, determine his effectiveness in removing casualty markers. Once used, the courier is removed; he's given his all. The table is:

|

These casualty markers can be removed from any unit on the field. Since the number of markers on a unit can be reduced, the casualty markers, thus interpreted, are not really "casualties" as such... rather, they represent a decrease in unit efficiency.

This is borne out by the casualty effect table, which gives the number of markers required to completely destroy a unit:

| Heavy cavalry or infantry Medium cavalry or infantry Light cavalry or infantry |

6 markers 5 markers 4 markers |

The force commander, therefore, from bound to bound, is required to commit his couriers to assist those units whose efficiency level he wants to hold high. The couriers, however, have other uses than removal of markers.

In midfield, I had one of my heavy infantry units charge an opposing medium unit. This proved not a wise thing to do. In a 1-on-1 situation, I would have beaten the mediums, but Bobius Labienus Hurstius brought in a support unit to assist the one I charged.

The basic chance for an allied unit to run across the field to assist in melee is 80 percent. This is modified by two factors:

| D | Subtract the distance, in inches, of the supporting unit from the unit it wants to assist. |

| WC | Subtract the distance of the Wing Commander from the melee. |

Here, the supporting unit was some 10 inches away, while the Wing Commander was 12 inches away, hence a total of 22 was subtracted from the basic 80 percent to get a net of 58 percent. Hurstius considered this too low a figure, and so he used one of the ubiquitous courier figures to assist.

Here, the assistance rendered by the courier is given by a percentage dice throw:

| 01 to 33 34 to 66 67 to 100 |

The courier adds 10% The courier adds 20% The courier adds 30% |

In this instance, the courier assisted with 20 points, and so the chance of the supporting unit to complete its 10 inch dash and assist totaled 58 + 20, or 78 percent. Hurstius' toss was successful, and so it was 2-on-1 against me. Our Caesarian ranks were so thin that I had no nearby units to call on in support.

The melee procedures follow those used in firing... lots of HD are tossed, and casualties registered on throws of 1, 2, and 3. Each medium unit receives 1 HD per stand, while each heavy unit receives 2 HD per stand.

Due to his two units, Hurstius tossed more dice than I and came up with more 1's, 2's and 3's. This could be termed the "casualty phase", and the appropriate number of casualty markers were placed on the field. After the markers were set down, we then had to determine which side actually won the melee. This was decided by two parameters:

| T | The type of your units involved. Each medium stand receives 1 point and each heavy stand receives 2 points. |

| M | The total number of markers you placed on the enemy. |

Each side calculates a Melee Product, P, and side with the highest product wins:

- P = 10-sided die x (T + M)

I lost the melee, and here's where the forces of the great Caesar began to crumble. The melee rules mandate that the loser selects one of his units that participated in the melee, and places it in the Rally Zone, an off-board holding-zone, where it remains until rallied.

Since I only had the one unit in combat, I had no choice... off it went to limbo-land to await the rallying phase.

What this did was to open a huge hole in Caesar's line; we had so few units to cover our frontage that every loss produced large gaps in the line.

But I wasn't worried yet... after all, we still had our ace-in-the-hole... our "surprise units" of heavy infantry which would come into play when the opposing cavalry charged in on our right flank.

And charge in they did. This was it! I opened the box which held our troops and set them out. To his credit, when our reserve units suddenly and magically appeared on the field, Hurstius didn't bat an eye ... he's well used to strange things happening during Simon scenarios.

On our right flank, we now had one medium infantry unit, one heavy cavalry unit, and two heavy infantry units. Each of these now went against a different unit of Hurstius'. My intention was to try and tie up every opposition unit, providing him with little opportunity for bringing in supports.

In part, it worked... Hurstius could support in only one of the four simultaneous melees.

Much dice tossing, many casualty figures used, many Melee Products calculated... and when it was all over, I had lost all four combats!!

So much for our surprise! And since the losing side must take a unit off the field and place it in the Rally Zone, all four of my units... the entire right flank... went into limbo. By the beard of Zeus, or Isis, or the Great Juju, or whomever, what had I done wrong?

It's fairly difficult to fight a battle with no right flank; trust me, I know.

And so our replay of Pharsalus ended disastrously for Caesar... in our search for historical accuracy, we had reversed history! I shall say no more.

Back to PW Review October 1995 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com