The occasion: Jim Butter's 70th birthday. The place: Bob Hurst's game room, his huge gaming table, and a lotta 25mm American Civil War troops. Five players per side, with General Jim commanding the entire Union army, at the same time taking personal command of its right flank. Whotta man!!

At first, we were going to have all troops off-table, and then we decided that if the battle was to have any sort of conclusion within, say, four hours, an off-table start was not the way to go.

I've noticed that, in our group at least, a game lasting more than 3 or 4 hours leads to name calling, shortness of breath, armwrestling, nose-tweaking, and the like. And so, in light of the solemnity of the occasion, we took great pains to preserve whatever friendships were in being at the start of the battle.

Terrain

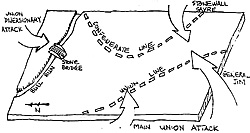

The sketch below shows the initial dispositions. Back on

July 21, 1861, Union General McDowell decided on (a) a

diversionary attack across Stone Bridge, while (b) the bulk of

his forces made a huge flanking move to hit the Confederates on

their left flank.

The sketch below shows the initial dispositions. Back on

July 21, 1861, Union General McDowell decided on (a) a

diversionary attack across Stone Bridge, while (b) the bulk of

his forces made a huge flanking move to hit the Confederates on

their left flank.

McDowell achieved an "almost"...it turned out that Stonewall Jackson saved the Confederate day by coming to the rescue in the nick o' time.

In our battle, Stonewall's role was played by Cliff Sayre, who was absolutely imperturbable throughout the battle, despite the constant flow of "Oh, by the way, I forgot to tell you..." messages he received from the umpire concerning the rules.

Despite the setup shown in the sketch, we all agreed, at battle's end, that we had still not set up close enough. Except for several units on the flanks of the armies, the centers of both forces never even made contact.

Tony Figlia and I commanded units in the middle of the Union line; we both vowed that our forces would deploy and fix bayonets at the beginning of the battle, and advance on the Confederate line without firing a single shot. A taste of cold steel we. just the thing for Johnny Reb, we thought.

Alas! We never made contact to prove our theory. The Rebel units which had been placed to greet us, came under continual supporting fire from our batteries, and few of them seemed to pass their morale tests... they sort of faded back from our advancing troops.

Organization

The 25mm unit organization followed along the lines of FIRE AND FURY:

- 1 stand was defined to be a regiment

Up to 8 stands constituted a brigade

4 brigades comprised a division.

Each player was assigned a division of 4 brigades plus one supporting gun model, defined as the divisional battery. These units, plus a division commander, gave each of the 10 players around 30 stands to push across the field.

Each time a unit (brigade) was hit, it received a casualty marker. No, gentlemen, not a casualty cap, not an "0" ring, not a toothpick... but a genyooine, all-American, apple pie, Tom Mix casualty figure, primed and painted by your author himself. Well, perhaps I exaggerate... the figures were more primed than painted... Anyhoo, when the brigade received a total of 3 casualty figures, one stand (a regiment) was whisked away, placed in the "Rally Zone," there to await its fate.

Rally Zone Mode

REVIEW readers will have noted, of late, that I'm in my Rally Zone rules mode. When casualties occur on the field, no one immediately dies. Instead a stand is wafted to this off- table, limbo land called the Rally Zone. Twice each bound, the sequence provides for a rally phase, and it's then that the stand discovers what's in "tore for it. A 10-sided die is tossed for each stand with the following results:

- 1,2,3: Regiment recovers, may be placed with a unit on the field

4,5,6: Regiment is destroyed

7,8,9,10: Regiment remains in Rally Zone, tests next rally phase.

Note that according to the above, the effective casualty rate is 30 percent, i.e., 30 percent of the time, a stand disappears. This figure is entirely theoretical, of course. I noted, for example, that when our beloved leader, General Butters, diced for the stands in our Union Rally Zone, his success rate was well below normal. I'd say around 50 percent of the stands for which he diced were destroyed, hence the nom de guerre which General Butters earned for himself... the Manassas Killer. Usually, a general oarns the sobriquet "Killer" for disposing of the enemy... war is hell.

Bob Hurst was in command of the Confederate force.... his rallying success rate remained unknown, sealed by the War Department and slated to be released in the year 2000.

I have already noted that my own division of 4 brigades did nothing but march toward the enemy during the battle... this gave me the opportunity to witness the goings-on on the Union right flank, where General Butters was driving his men forward.

Directly in front of General Jim Butters' forces were those of Stonewall Sayre. Stonewall, however, was not permitted to come on to the field until Bound #2. This gave General Jim two advantages:

- First, his right flank units started out in

midfield

Second, because of the one turn delay of the appearance of Stonewall,s troops, General Jim's Union forces had yet another one-turn's move.

The result was that one of the General's 8-regiment brigades raced forward and reached a point on a ridge line about 18 inches from the Confederate baseline even before the Confederates were scheduled to appear. This sounds rather advantageous, but all was not solid gold.

Jim's 25mm division commander was in charge of 4 brigades. Three of them were well to the rear of the advance unit, and the division commander was with the rear units. He was so placed because these rear units were under continual Confederate artillery fire, continually having to take morale tests, and the proximity of the commander is a help in passing these tests.

Morale

Each brigade is given a morale level defined as a certain percentage (proportional to the number of regiments it contains), and from this level is subtracted the distance to the division commander. Which means that if the commander was placed to the rear to support the rear brigades, he was relatively far from the advanced brigade.

The division commander affected the actual morale level of a brigade in two ways:

- First, as just noted, his distance,

in inches, was subtracted from the morale percentage.

Second, the division commander was given a series, i.e., a specific listing, of morale augmentation points with which he could bolster the morale level of his units.

General Jim's division commander was some 20 inches from his advanced brigade, and thus when Stonewall Sayre's men appeared and peppered away at the brigade, it deducted 20 from its basic morale percentage on every morale test. The good General Butters then brought the morale level back up by taking a number from his division commander's listing of morale modifiers.

For the first several volleys, General Jim was able, by means of the listing of "plus" modifiers, to help the brigade to pass its morale tests, and it held position. But the division commander simply ran out of modifiers... he was helping, not only the advanced brigade, but the other three who were absorbing artillery fire. The advanced brigade fell back; it failed a morale test and wisely retreated.

Now that Stonewall Sayre's men had finally appeared, it was his turn to go on the offensive. On the Confederate's active phase, he advanced one brigade to within melee range of one of General Butter's brigades. Ordinarily, there'd be nothing exciting about this, except that this time, the Butter's brigade was caught in column formation. Sometime previously, General Butters had marched his men up in column, had tried to deploy, and had failed.

On a side's active phase, each of its units was given 3 actions on each of which the unit could fire, change face, change formation, or simply move. Every action devoted to a formation change contributed 25 percent to the success of completing the evolution. Hence if all 3 actions were given to the formation change, there would be a 3 x 25, or 75 percent chance to reform.

Unfortunately for the Butter's brigade, it had moved up, failed its attempt to change formation, and so remained in column. Being in march column, the unit had no chance to fire in its own defense, and we went to the melee procedures. Melee takes place in 4 steps.

Melee Steps

1. First, there's an "impact" phase, simply resolved by comparing the number of stands involved. General Jim's brigade had 8 stands, as did Stonewall's. But the Butter's brigade was penalized for being caught in column; it fought with only 2 of its stands instead of the full 8. Thus, for "impact," 2 Butter's stand. met head on with 8 of Stonewall's stands.

Butters' 2 plus Stonewall's 8 gave a total of 10 stands in combat. Since Butters had 2 of the 10, he had 2/10 chance, i.e., 20%, chance of immediately knocking off a Stonewall stand. Conversely, Stonewall had 8/10, or 80% of immediately knocking off one of Butter's stands. Butters failed, while Stonewall succeeded.

Second, there's a melee phase for bringing in a supporting unit. Here, both division commanders had been graded in terms of movement points. I think that the Union officer had been given 15 movement points, which meant that he could move a total of 15 inches... the distance to move to a supporting unit, plus the distance to escort the unit into combat.

General Jim had one potential supporting unit. His officer moved to it, and tried to persuade it to assist (70 percent chance of success)... no use, the unit failed to budge. A second chance is not allowed.

Stonewall Sayre had a couple of units nearby, but none was deployed, hence by definition, was not allowed to assist.

The result was that only 2 of Jim's 8 stands (remember, his unit was in column) faced all 8 of Stonewall's.

The third phase consists of the stands in combat bashing away at each other. Each stand gets a 10- sided die, and the resultant roll is:

- 1 Stand immediately goes to Rally Zone, may be

rallied later

2,3 Stand backs out of combat, will not participate further in the melee.

4 to 10 No effect

Here, Stonewall's 8 stands provided 8 dice, while Jim only received 2. But both Generals tossed in additional dice, obtained from the division commander. Each had been given 8 Combat Dice to be used to assist their units in melee. Once the Combat Dice are used up, they are not replenished. I'm not sure how many Combat Dice were committed, but both commanders tossed a handful of dice, with Stonewall's being proportionately greater (he had around 12 dice) than Jim's.

The 4th and final melee phase concerns the determination of which side actually won, i.e., which side holds the ground. Here, two parameters are used: the number of stands, 8, remaining in combat, and the numbor of enemy stands, E, which were either sent to the Rally Zone or forced back out of the combat.

The sum of S+E is multiplied by a die roll and the higher product wins. Despite the low number of stands he had knocked out of combat (giving him a low multiplier), General Jim tossed extremely high, Stonewall Sayre tossed extremely low... and the Union brigade won!!

Stonewall Retreats

The Stonewall brigade retreated in pure ahistoric fashion. I've noted that, for some reason, whenever our group attempts to recreate an historic battle, the results seem to disagree with those related in the history books.

And so it was, this time too.

In the center of the field, as my division and that of Tony Figlia's advanced with fixed bayonets, the two opposing Confederate generals, Bill Rankin and Stephan Patejak, had at first lined up their unit. to face the assault.

We Unionists had supporting artillery fire, and in the face of all those cannonballs (do cannonballs have faces?), the Confederates seem to dissolve.

It wasn't really the cannon balls that did it, since artillery wasn't that effective. What truly caused the Confederate troops to move back was a consistent series of poor Confederate dice throw. when the units, having taken a casualty or so, took their requiaite morale tests.

Neither Confederate general seemed to be able to toss low, below the required morale level. In one instance, I remember that Bill Rankin had deployed a cavalry brigade in front of my advancing troops, and I mentally noted that there was trouble ahead.

My attention was diverted to one of the flanks for about two minutes, and when I looked back, the threatening cavalry was seen no longer.

"Wha hoppen!" I asked Bill, and he muttered something about a failed morale test.

In most of my rules sets, officers are provided with the ability to augment the morale level of their troops. The officers are given perhaps 10 numbers, ranging from 5 to 30, to choose from. They then select whatever number or numbers they desire to add to the morale level. With a finite number of choices, there is a tendency to "chintz" i.e., to add only a wee bit at a time and make the assortment of given numbers last as long as possible. I do this myself... if a unit's morale grade is, say, 60%, then I'll add only 20% to bring it up to a total of 80%... surely I can toss dice below 80??

The contrary theory is espoused by Tom Elsworth. Tom's theory can be stated succinctly: "if you've got it, use it." Tom will toss in sufficient augmentation to bring his units to a perfect 100. Only when he completely runs out of numbers will his units fall back.

The Confederate generals in our battle were wedded to the chintz theory. They used minimum augmentation. The result?... a glorious victory for General Jim Butters, the Manassas Killer!

Back to PW Review November 1995 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com