I dusted off a very old set of Seven Years War (SYW) gaming rules, and tried to bring them up to date.

I dusted off a very old set of Seven Years War (SYW) gaming rules, and tried to bring them up to date.

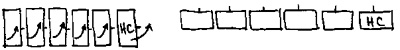

The heart of the rules system was the sequence, governed by the draw of action cards, on each of which was noted 3 to 6 actions. Here, the thought was that, during the SYW, the honor company must always be on the right of a formation, or, if a unit was in column, in the lead. The illustration below shows the desired location of the honor companies. Note that each unit, i.e., each battalion, is composed of 6 stands... each stand represents a company, and 3 stands are defined as a section.

As shown, the permitted formations were three in number: column, single line and double line.

As shown, the permitted formations were three in number: column, single line and double line.

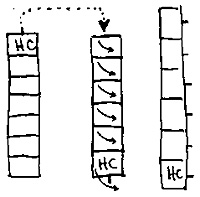

Note that if a battalion is in column, and the desired maneuver is to form a single line facing to the left, all that the individual companies in the unit are required to do is to make a simultaneous left wheel, and presto!, the honor company automatically finds itself on the right, and the entire battalion is ready to go.

In contrast, if the desired evolution is to form line facing to the right, the entire battalion has to perform a "walk-about", following the honor company in a clock-wise maneuver, until that company finds itself on the right, at which time, all companies perform a simultaneous wheel to the left.

In contrast, if the desired evolution is to form line facing to the right, the entire battalion has to perform a "walk-about", following the honor company in a clock-wise maneuver, until that company finds itself on the right, at which time, all companies perform a simultaneous wheel to the left.

To implement this on the gaming table, I drew up a table of required actions, a portion of which is shown below:

| To Go From | To | Number Of Required Actions Is |

|---|---|---|

| Column | Single line facing left | 2 |

| Column | Single line Facing right | 4 |

| single line | Column facing right | 2 |

| single line | Column facing left | 4 |

Each half of the bound, the active side drew an action card at random, and the noted number of actions (3 through 6) determined if a maneuver could be completed that bound, or if the maneuver required more actions and had to wait until the subsequent bound to be finished.

As an example, assume a unit is in column, facing north, and wants to form single line facing east, to the right. The table states that 4 actions are required to complete this maneuver.

If the side drew a 3-action card, therefore, the maneuver could not be completed. Most of the unit would be in place, but at the end of the 3 actions, there would still be elements of the battalion marching to assume their position. The entire maneuver, therefore, would have to wait until the next bound to be completed.

Until all companies were in their proper place, the unit would suffer in both fire and melee. Firing was not permitted until the evolution was finished, hence it was possible for a unit to be outmaneuvered, and have to take enemy fire while it was still maneuvering.

We set up a fairly small battle to test the above. I defended and Fred Haub attacked across a river line. In contrast to the standard "dice-throw-of-70-or-under-to-cross" rivers we usually use, this was a veritable raging torrent needing a "dice-throw-of-50-orunder-to-cross".

All infantry regiments were composed of 2 battalions, and each battalion had 6 stands, termed companies. Data sheets were used, but instead of tracking the individual battalion, the regiments themselves were the entities whose factors were noted on the sheets.

Cavalry regiments consisted of 2 squadrons, each of 4 stands.

Each regiment had a data sheet that looked like this:

100 60 40

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Note that the regiment had 15 boxes to be crossed out before it was removed from the field. And note that the entire regiment went, not just one of its component battalions.

The casualty determination procedure was a 2-phase affair:

- (a). During the half bound, hits were inflicted on the target unit, and a marker would be placed next to the regimental officer when one of three things took place: (a) when the active side fired offensively, (b) when the non-active side fired in defense, and (c) when melee took place.

(b). At the end of the half-bound, the effect of all the markers present taken would be assessed, and at that time, hits would be noted on the data sheets. Dice would be tossed for each marker on a regiment, and the following table used:

- 01 to 33 1 box per marker

34 to 66 2 boxes per marker

67 to 100 3 boxes per marker

Note that a regiment with, say, 4 markers on it, if it was lucky and tossed low dice (a number below 33) during the assessment phase, could wind up with only 4 boxes, out of its total of 15, crossed out. In contrast, an unlucky unit, by tossing consistently high, could discover that 12 boxes had gone.

If, during the consecutive firing and melee phases of a single half-bound, a regiment took many, many markers, it was possible that when the marker assessment phase occured, all of the regiment's allotment of boxes were crossed out, i.e., the regiment was removed.

This was the case in a second game we set up. On my left flank were three regiments comprising colonel Gauche's brigade. One of the regiments advanced in column formation, but didn't have enough actions to fully deploy into a line facing straight ahead.

My lead battalion found itself with 3 of its 6 stands deployed, the other 3 still in column, ready to move into line on my next active phase. The second battalion of the regiment was in the same formation. Alas! The lead unit never got the chance to fully deploy. The opposing player, John Shirey, already had his men in line, and with a judicious use of his actions, on his active half of the bound, he fired and advanced into contact.

My lead battalion picked up several markers from the firing procedures, and picked up even more during the ensuing melee. At the end of the half-bound, when the markers were translated into actual hits on the regiment, I found out that all of its boxes had disappeared, and, therefore, so did the regiment.

The melee procedures account for the fact that a unit may be unlucky enough to be caught while deploying. For purposes of melee, each 6-stand infantry battalion is divided into two sections of 3stands each; each section gets a die to roll, but only if the section is deployed.

When melee begins, a deck of 12 cards is called upon; each card will state two things:

- a. How many sections will be allowed to strike, i.e., toss a die. If a section is not fully deployed, it is not permitted a die. Since an entire regiment of 2 battalions may be involved in the combat, and the 2 battalions of 6stands consist of a total of four 3-stand sections, provisions are made in the card deck for anywhere from 1 section to 4 sections striking.

b. The second annotation on the cards of the melee deck states how many stands will be allowed to deploy. Thus as the melee continues, and more cards are drawn, an increasing number of the stands of the units in combat get to deploy and enter the fight. This means that a unit caught in column of march (no stands deployed), will get zapped for a couple of card draws as its opponent gets its first strikes in; with the play of each card, however, as more and more of the surprised unit's stands deploy from column into line, the unit will eventually get to fight back.

The other item of interest concerns the victory conditions. Note on the regimental data sheet given on the third page of this article that above the boxes is a row containing three numbers, termed Efficiency Points (EP) : 100, 60 and 40. Until the first 5 boxes are crossed out, the regiment is "worth" 100 EP.

Then for the next 5 boxes, it's worth 60 points, and so on.

My cavalry brigade, for example, had three regiments, each starting at 100 points, giving a brigade value of 300 EP.

As the brigade took losses, the totals of its EP values decreased. Sometime around the fifth turn, one regiment of two squadrons was completely wiped out, while the other two totaled, between them, 120 EP (they had 60 EP each).

The ratio of the current EP total of 120 to the original value of 300 is 120/300, or 40 percent. This 40% figure is called the brigade's Efficiency Ratio (ER).

This ER percentage, 40%, is the probability of the brigade remaining as a fighting force on the field. But the percentage is tested only when the opposing side calls it into question.

When a side feels that one of the opposing brigades is fairly weak, i.e., its EP total is way down, and therefore, its ER percentage is very low, it may challenge that brigade. The challenge is affected by requesting the opposing commander to toss percentage dice below the ER.

In my case, I had to throw percentage dice below 40... which I failed to do.

The penalty for failing the test is that the entire brigade must immediately exit the field. With one of my three brigades thus fleeing, it was obvious that the battle was over.

These challenges are issued without knowing the ER's of the opposing brigades. Since figures are not removed, and unit sizes are thus never reduced, all a player can know is that an opposing brigade has been hit pretty hard, and its total ER should be down, and it might be ripe for a challenge.

The challenges appear to be a simple way to set up victory conditions such that it becomes impossible for a side to continue the battle.

The challenge, however, can backfire. If the challenged side does meet the challenge and toss its dice successfully, i.e., toss below its ER percentage, then the challenger must lose one complete regiment.

And when a regiment goes, so goes its EP of 100 points, and the challenger's mother brigade's ER goes down accordingly, making the challenger's brigade ripe for a counter challenge.

This is exactly what happened to me. I thought I had hit the opposing cavalry brigade, over the course of several turns, fairly hard, and that its ER percentage should be down.

So I challenged.

I misjudged greatly. It turned out that the three cavalry regiments had EP values of 100, 60 and 60, a total of 220. The resultant ER percentage of 220/300 equaled 73 percent.

My opponents threw the dice and passed easily. At that point, since they had successfully met the challenge, I had to remove one of my own regiments.

So as to not let the challenge syndrome get completely out of hand, each side is limited to only three challenges throughout the battle.

Back to PW Review February 1995 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com