The HMGS COLD WARS convention took place, as usual, March 3,4,5 (Friday, Saturday, Sunday) at the Lancaster Resort Hotel, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Bob Watts, the HMGS Program Manager, indicated that on Friday alone, over 1,000 people were present. I never did get the final registration figures.

As Bob said, even if HMGS didn't advertise the event, and nothing was said about it, there would still be enough people coming to Lancaster to register to hold a convention.

Bob presided at the HMGS meeting, and immediately stated that this was to be an "information only" meeting, i.e., no business was to be transacted. The HMGS Prez, Pat Condray, wouldn't be able to attend and the only order of the day was to keep the membership informed of various goings-on. With that in mind, the Treasurer, Dick Sossi, was called on and stated that HMGS had $48,000 in the bank, a report on HISTORICON by Bob Coggin's replacement followed, and a summary of the recommendations of the Write-A-New-Set-Of-Bylaws Committee was given.

In all, a quiet, orderly meeting, which actually followed Robert's Rules Of Order. Bob Watts handled himself well.

As for games, I wandered through the halls in my usual mode, seeking new, novel, innovative ideas... not too many of them. Terry Sirk sat through a battle of KNIGHTS AND KNAVES (KAK), a set of medieval skirmish rules. Terry offered to guide me through a second game, and we sat down at the table. There were between 30 to 40 25mm figures per side.

Unfortunately, the game proceeded at an extremely slow pace, exacerbated by the fact that the entire center of the table was taken up by a lake... which meant that both sides had to take the long route to come into contact. The result was that nothing seemed to be going on except bowpersons firing at each other, with the result that casualties took place, and figures were pushed over on their side when hit... a sorry spectacle. Bows ranged out to 72 inches, a fairly long range, and both sides seemed to be extremely cautious about closing.

I gave up and when, eventually, I returned, about an hour later, the majority of men on the field had been tipped over, and the few that remained were engaged in hand-to-hand combat. Alas! I cannot comment on KAK itself, other than to say the set up, complete with castle, looked rather good.

Volley and Bayonet

VOLLEY AND BAYONET (VAB) is a newly published set of rules covering the 1700's and 1800's. VAB first appeared in Hal Thinglum's MWAN. Our group tried a game or so, I reported on it in the November/December 1994 issue, and had not-too-many good things to say.

The authors, Frank Chadwick and Gregg Novak, were on hand at COLD WARS to present their creation. I thought they did it in an extremely effective way. They set up the battle of Guilford Courthouse in 54mm, of all things. Three figures per stand, while light units had a single figure mounted on a stand.

VAB is a large scale game... one inch represents 100 yards, and movement distances are of the order of 16 inches for infantry, i.e., 1600 yards. The MWAN article stated that a turn equaled an hour, and one stand (3-inch frontage) would represent an entire brigade of some 600? 700? men.

In the COLD WARS presentation with 54mm figures, a brigade seemed to consist of 2 stands... each stand representing 300 men. Each unit was tracked on a data sheet, and disappeared when it took a certain number of hits.

One interesting rule was that if a unit remained stationary, and sat in place, it received a "stationary marker", which allowed it to double its dice in fire and combat. In part, this was in accord with the Simon thought that during this era, troops on the defense, not using their time to advance, could concentrate fire. I'm not sure about the additional dice in melee, however.

Bob Wiltrout was found table-side, commanding the American Virginia Militia, a 2-stand unit. The Virginians did a fine job of standing up to the oncoming British regulars, but after a turn or so in contact, one stand fled.. the result of a poor morale test.

Having fled, the entire unit was termed "exhausted" and the remaining stand fought at a disadvantage. Bob's thought was that the remaining stand should not be taxed because its sister stand ran; in fact, having stood toe-to-toe with the British, the remaining stand should get a bunch of "pluses".

We quickly decided that the term "exhausted" was the wrong one to use. Perhaps "disappointed' or "disheartened" would have been a better choice of words.

I noted that the American commander, General Greene, raced after the militia stand to rally it. At his mere touch, it rallied automatically. I also noted that later in the convention, Messrs. Chadwick and Novak presented another VAB game, this time in 15mm scale.

Perhaps because of the many players involved, the pace of the game was rather slow. One of the American players, trying to speed things up a wee bit, kept shouting (in my good ear) : "ARE THE BRITS DONE MOVING? GOTTA KEEP THE GAME GOING!"

I thought the 54mm game looked well; "A nice skirmish game", was my comment. "No", said Bob, pushing his 54mm, 6-figure, 2 stand unit around, "This is not a skirmish game." Obviously, this was serious stuff, and I said no more.

Bob also showed up at a game of POUR LE MERITE (PLM), presented by a Virginia group to which Scott Holder belongs. Scott is a PW member, and he was impressed by PLM (rightly so!), a Seven Years War set of rules crafted at my own ping pong table. He showed it to the Virginia boys, and they adopted it for their own SYW games. Their COLD WARS presentation was the battle of Freeman's Farm.

The Virginia PLM version (VPLM) is somewhat changed from the original. VPLM uses the concept of "actions", i.e., each side dices for the number of actions all of its units receive each bound to fire, move, etc. It does not use the universal, inter-galactic 70 percent rule for passing through rough terrain.

VPLM, however, like the original, does use Command Points (CP), wherein an officer can temporarily augment the morale level of a unit under stress.

Bob Wiltrout's comment was to the effect that he was watching and enjoying VPLM until he heard mention of "Command Points", at which time, he choked up, gagged a wee bit, and ran to the men's room. Bob questions the CP symbolism... what is it that the officer is doing to the unit when he "donates" CP to it? What exactly is he "giving away"? What sort of storage chest does he draw from when he plucks out a handful of CP and says "Here! Take some!"

Alas! I have no definitive answer to these keen and piercing questions. I only know that the officer "helps" his units and that because the morale tests use "numbers", the officer's assistance is given in "numbers". If the morale tests used eggs, I'd give the officer a handful of eggs with which to help out. I'm easy to get along with...

Of interest to me was Bob's comment (this doesn't mean that his other comments were of no interest; it's just that they were of lesser interest) concerning the use of a magical, mystical aura surrounding an officer. He said he could see giving a unit "plus 1" if an officer was attached, and a "minus 1" if he was 6 inches away, and so on.

It seemed to me these were still "numbers"; no matter how you cut it, no matter what the game mechanics, the numbers pop up. I should note we didn't discuss eggs at all.

But why am I digressing!

Let's get back to COLD WARS.

John Shirey ran the DBM tournament, and indicated that there were some 40 people enrolled. This was about equal to the numbers signed up for the WRG 7th Edition tournament.

In the flea market and dealers' area, there were all sorts of DBA armies for sale.

Everyone wants to cash in on this extremely accurate and historical simulation which always uses 12 stands per side to re-create any battle in history. DBA armies of 12 stands could be purchased for anywhere from $20 to $60, and were available in both 15mm and 25mm scale.

The COMMAND DECISION boys were out in full force. Many, many COMMAND DECISION games. One group from Kansas set up the battle of Kursk (or, rather, a piece of it). Their terrain boards measured 4 feet across, and 32 inches in depth. The field used two of these abreast, and some 12 boards deep, giving a table dimension of 8 feet by 27 feet.

The battle was fought along the long dimension, and I can assure you that there were more than enough tanks and guns and halftracks and vehicles on the field.

As usual, the sides seemed to "form phalanx" with their tanks; a dozen of them shoulder to shoulder as they advanced. I checked with a PW member, an ex-tankie, who had served in Desert Storm. About the only time his unit "formed phalanx", he said, was at night when they parked close to each other to concentrate their fire. Other than that, they made sure they maintained some distance apart when advancing.

In another room, the battle of Gettysburg was set up. I mention this in conjunction with the set up of the battle of Kursk because both fields, Gettysburg and Kursk, consisting of terrain boards, were "uni-battle" oriented. They were not geomorphic, i.e., they couldn't be reoriented to produce another battlefield.

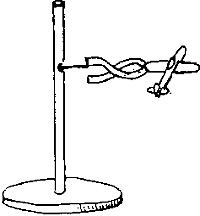

There were several airplane games. One dealer was selling some neat-looking 1-inch-long aircraft, together with vertical dowels to hold them aloft, and the majority of airplane games seemed to use his products. One mounts the plane in an alligator clip which is itself attached to the dowel, permitting the airplane to assume any configuration desired.

A sketch of his supporting mechanism is shown below. The problem is that the alligator clip is as big as the aircraft itself, and so what one sees is not merely a flight of planes cruising by, but a swarm of overhead alligator clips.

A sketch of his supporting mechanism is shown below. The problem is that the alligator clip is as big as the aircraft itself, and so what one sees is not merely a flight of planes cruising by, but a swarm of overhead alligator clips.

One airplane game concerned a 1/700 scale WW II aircraft scenario, an attack on an aircraft carrier, in a fairly small area. As I said, except for the alligator clips, it was a neat set-up.

Good Samaritan Tale

And now for my good Samaritan tale of the day. At the convention, there was an 11? 12? year old kid, confined to a wheel chair, who pushed himself along rather adroitly. As I was walking down the hallway, our paths paralleled, and he said: "Pardon me, do you know where the Pee Room is?"

"Certainly", I replied, "We'll pass it in a minute. There it is, right by the Ladies' Room."

As I left him at the door to the Mens' Room, I noted him staring after me quizzically.

About five minutes later, I overheard two people talking: "There's a great game in the Paradise Room; let's get up to the Pee Room to see if we can get in."

The light; the dawning. My young friend didn't want the Pee Room; he wanted the Pee Room!

To my credit, when next I saw the lad, I went up to him and explained my mistake. I was absolved of blame.

Guest Speakers

During the convention, there were a series of guest speakers on all sorts of topics. I attended four of them, all rather interesting. The first concerned the history of the USS Olympia, Admiral Dewey's flagship during his attack in Manila Harbor in 1898. The second concerned re-enactments, in particular, the Battle of the Bulge.

This second talk was not concerned with the nitty-gritty of reenactments, rather, it was oriented toward the philosophical end of the spectrum... for example, the speaker stated that re-enactors were "heirs to history"... that sort of approach.

Unfortunately, both speakers read their papers, instead of presenting them in an off-the-cuff format. The third presentation, on the Falklands War, was more informal, as the speaker told of the events leading up to the conflict.

Here, however, we had a problem. The lecturer was continually interrupted by a number of all-wise members of the audience, who asked questions... not because they wanted to know the answer, but because they already knew the answer, and wanted to show the rest of the audience how clever they were.

Alas! I fell asleep during the talk, awakened by a nudge from Fred Haub, in time to hear about how the Argentinean ship, the Belgrano, blew up.

The fourth lecture I attended was on Napoleonic cavalry tactics, and despite the sworn statements of Bob Wiltrout, Bob Hurst, and Fred Haub to the contrary, I am willing to testify in open court, under oath, that I did not fall asleep.

They allege I was snoring... about the only thing they do not accuse me of is shouting in my sleep: "O' baby! O' baby! Do it! Do it! Don't stop!"

Are these my friends??

Rich Hasenaeur presented his soon-to-be-published WW II armor rules. Like all Hasenaeur efforts, this was professionally done... multi-color "cheat sheets", beautifully painted 15mm armor, and the like. Looking at the field, I noted a plethora of chitties, some, I would assume, representing orders, others representing "hidden units".

The game was given at least two times, and Bob Hurst wanted in on the second go-round. He sat down on the German side of the field; his unit, some 8 tank models (each model represents 2 vehicles) not quite on the table.

And he sat and sat and sat. Bob and I always fall victim to the "You've got the reserve" syndrome... which means that the forces under our command will get on the table around Turn #87... if we're lucky, and live long enough.

I visited Bob during the game, dropping by every three days (or so it seemed), and the report was always the same: no, his units weren't quite there yet.

Finally, Bob gave up the ghost, stating that the real reason he left was that one of the Allied players was too noisy, becoming a big pain in the process.

I observed one of Ed Mohrmann's "no-rules" games, at least, that's what it looked like as Ed winged his way through the scenario. He was hosting an ECW skirmish affair, and several villagers were whomping, or trying to whomp, some of the King's men. Evidently, there was a big melee in the tavern, as 7 townsfolk attacked 3 soldiers.

When the villagers tossed all their melee dice, their total doubled that of the soldiers. From what I could gather, this was a bad thing for the military.

As Ed was handing out the melee dice, he'd give a die for a pitchfork, a die for a rake, etc. One villager toted an oar for attack purposes, which didn't seem the handiest weapon for the restricted space within the tavern. I'm not sure if he got a full die or not.

Regardless, Ed conducted his scenario with great aplomb, answering all questions without benefit of a set of printed rules. Whatever he ruled was accepted by his audience. Ed ran another game in similar fashion, and I noted yet a third game he hosted, one for the kiddies.

This game was a Napoleonics effort of single mounted 30mm figures. The table was surrounded by a horde of shouting, screaming, squalling kiddies, and one bellowing host, with Ed loving every minute of it. At the time, I was seated at the KNIGHTS AND KNAVES table, and I could hear Ed's voice over that of the mob.

Napoleonic Storming

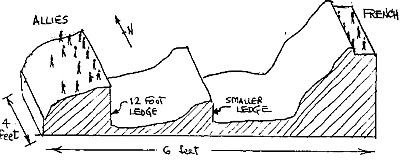

One of the most interesting presentations was that of Jim Birdseye. He hosted a Napoleonic "storm the breach" scenario. His terrain is sketched below; the attacking force coming in from the west, and the French defending the walls on the eastern side of the table.

The allied force of British and Spanish had to jump down into the moat, make its way across, jumping down yet another ledge, and scale the walls, all this under enemy fire.

The allied force of British and Spanish had to jump down into the moat, make its way across, jumping down yet another ledge, and scale the walls, all this under enemy fire.

There were 100 Allied figures. On the walls waited 20 Frenchmen and five cannon.

In the Allied van was a group of around 17 British Riflemen. They were first to jump down the 12 feet into the gully. And even before the Brits reached the ledge, the force lost 4 men to French fire. After jumping off the ledge, each man tossed a die... on a toss of 1 or 2, they landed safely, on their feet. Most did not land vertically.

Immediately after the Rifles jumped, it was the turn of a Spanish unit. Unfortunately, they did not give the Rifles time to clear the base of the ledge, and most of them landed comfortably on top of the Rifles, breaking heads and ribs and arms, etc.

This was a bad thing for the Rifles, and Jim Birdseye's comment was to the effect that this was "poor jump planning".

I did not stay around for the exciting climax as the Allied force fought its way across the moat; Mark McLaughlin reported, however, that of the 100 Allied men starting out, 42 made it to the wall, but they couldn't drive the French back.

Each man, when he fired, was marked as having an unloaded weapon, and had to take a turn to reload.

Chariot Races

I noted the presentation of two chariot races during the convention. One was for the kiddies, and the host, just as Ed Mohrmann did during his own kiddy game, enjoyed himself immensely. This chariot race took place on a field of 3-inch hexes. The team of horses was in one hex, while the chariot was in an adjacent hex. The placement allowed a certain amount of flexibility between chariot and team as indicated in the diagram below, showing what could occur as the chariot swung to a side when making a turn. As the chariot shifted position behind the team, it could be placed in one of three hexes:

I noted the presentation of two chariot races during the convention. One was for the kiddies, and the host, just as Ed Mohrmann did during his own kiddy game, enjoyed himself immensely. This chariot race took place on a field of 3-inch hexes. The team of horses was in one hex, while the chariot was in an adjacent hex. The placement allowed a certain amount of flexibility between chariot and team as indicated in the diagram below, showing what could occur as the chariot swung to a side when making a turn. As the chariot shifted position behind the team, it could be placed in one of three hexes:

All sorts of horrible things were listed on a series of charts perched high above the players. There were loose wheel charts and overturn charts and carom charts and so on.

One participant's chariot had a damaged wheel as he entered a turn - evidently going too fast - and the host shouted: You have a loose wheel... throw a die!"

The die was tossed and the host chimed in again: "You've lost your right wheel, your only remaining wheel is your left, and since it's your best wheel, you'd better take care of it!"

The player did not take care of his wheel... one bound later, his chariot overturned.

The other chariot game was hosted by Jeff Wiltrout, one of our PW boys. He presented a game devised by Brian Dewitt, which used squares, and in which both chariot and team were modeled together and were placed in the same square. The Wiltrout/Dewitt race was definitely several orders of complexity above that of the other race; this was not kid-stuff.

Inverse Pip Theoiry (IPT) A Discourse

W. Simon,

Fellow, Centre for Provocative Wargaming Analysis

The formulation of the Inverse Pip Theory (IPT) was my instantaneous reaction to the 'pip-movement' provisions of the two sets of rules, DBA and DBM.

In these two sets, one tosses a 6-sided die each turn, and moves the number of groups indicated by the number of pips showing on the die. All other units must remain stationary, immobile. The rules state they are not in 'control', and not being in 'control', they cannot move, they cannot shift position, they cannot scratch their backs, and they must sit in comatose fashion until hopefully rescued on the next turn by a better die toss.

This did not sit well with me. Why, I asked myself, should units or groups on the battlefield, in close proximity to the enemy, in consecutive twenty minute increments (depending upon the length of the turn), first advance, then halt and glare at their opponents, then advance again, then halt, and so on?

It seemed to me that once these units on the field were given their initial orders, and the general direction of the enemy pointed out, they would start to march forward to meet the opposition, and continue to do so until they received orders to the contrary. They would not, on their own, go forward in fits and starts... first advance and then halt and then advance and then halt, etc.

And thereby was born IPT. Instead of units 'not in control' sitting rather dumbly and placidly within grinning distance of the enemy, with the troops sucking their collective thumbs, they would continue to advance, attempting to make contact. In other words, the definition of 'control' was reversed. Under DBA/DBM, units will halt if 'not in control'; under IPT, they will advance if 'not in control'.

I tried out the IPT concept with varying degrees of success. For the first few cuts, the number of controlled units was kept to a minimum; one determined the number of controlled units on his side, and then all other units would shout and rush forward like blazes to contact the enemy. The resultant setup could be defined as a 'non-game'... it was interesting, but the player-participant had nothing to do except watch as his units surged forward. He was turned into an observer; having lost control of these advancing units, there was nothing he could do with them.

Rules outlines were generated for the ancients period, for Napoleonics, for the American Civil War. Last year, Tom Elsworth and I applied a simple system to the renaissance period. A series of procedures gradually developed, procedures which actually made sense (!), and which, at the same time, kept the participant active in his role as a player.

In mid-February, I presented the latest rules set, one formatted for the ACW. This set incorporated just about all the ploys and procedures developed to-date. Unfortunately, the key ingredient was lacking... a set of specific victory conditions... and so the game ground on and on and on. I can usually tell when too-much becomes too-much because there are two members of our group who act as live indicators (perhaps 'live' is too strong a word), each providing a signal that the time has come.

In this case, the two members were facing each other across the table, Tony Figlia as a Confederate commander, and Fred Haub in charge of the Union. About 8 turns into the game, Tony's eyes glazed over, and Fred left the table, sat down in a corner of the room, and commenced to read a book..

This, I thought to myself, is the signal that it's time to stop. And so, stop we did, and while we were popping the figures back in their boxes, we turned our attention to a wee bit of philosophy about the IPT concept.

Dr. Brian Dewitt commented that, while the rules worked well, the theory was misplaced. IPT, said he, was really not applicable to the ACW era. Dr. Dewitt is a fellow Fellow at the Centre for Provocative Wargaming Analysis, and so his remarks were not to be ignored (although I made a mental note to bring his name before the Board of Directors for a second, more in-depth look at his qualifications).

IPT might be applicable... continued Dr. Dewitt... to the ancients period and up to the renaissance era, but beyond that, there wasn't that much 'lack of control' of forces in the field. In the Napoleonic era and thereafter, he said, the commanders of the units on the field (brigades, regiments, etc.) didn't simultaneously suddenly all go haywire and order their units to dash forward to contact at double speed.

I didn't fully agree with Dr. Dewitt (meanwhile thinking that perhaps a third, much greater in-depth review of his qualifications would be necessary). If one reads the history of these eras (and I have fully researched all the periods in contention, continually scanning and rescanning my copies of Classic Comics for pertinent information), one finds that the accounts of the battles are full of tales of units going off on their own, of disobeying orders, of attacking east instead of west, of arriving late, of never arriving at all, of not forming up in time, etc., etc.

If one were to try and implement all of these situations, one would face the problem of the 'non-game', not to mention the problem of the fractious player.

For example, tell a player that his units won't come on the field until Turn #25 because the commander misread his orders, and one has an unhappy and sorely vexed player to contend with, a player with nothing to do.

Tell a player that his units must fall back off the table, because the commander has confused east with west and north with south, and one has a very peeved player to contend with.

Tell a player that his units must remain in place because the commander isn't sure of what his orders mean, and one has an extremely cross player to contend with.

In short, during the game, and I stress game instead of battle, the participants want to play. They do not want to be the victim of a ploy, supposedly reproducing what actually went on in a battle that occurred during the era of interest, but that, in the game, reduces their participation to zero.

Several of the participants in our game voiced similar thoughts. Control of their units was taken out of their hands, and this, by definition, was a bad thing.

What I had done for the ACW game was to generate a table used by each division commander. Each commander, in charge of two to four brigades, was given a Control Rating (CR) of, say, 70%, and each turn, on his half of the bound, he'd dice on the following chart: --------------------------- 3 brigades out of control CR ---------------------------1 brigade out of control 1/2 CR ---------------------------All units in control ---------------------------

With a CR of 70, and a dice throw of over 70, the division commander would find that 3 of his brigades would rush forward, whether he liked it or not.

With a dice throw of under 35, he retained control of all of his brigades.

In truth, I thought the game proceeded smoothly, with relatively few hitches, but the clamor over the control function, while not quite deafening, was certainly there to be heard.

Bob Hurst had a suggestion that might ease the lack-of-control problem, which will be tried out in the future. It had to do with the fact that each turn, on its active half of the bound, a side diced for the number of actions (3, 4 or 5) each of its units would receive.

Infantry, if uncontrolled, could zip up the field at 5 inches per action; if 5 actions were called for, therefore, the unit could advance some 25 inches. Controlled units moved somewhat slower, only 3 inches per action; the "5" would permit them to advance only 15 inches.

Bob's thought was to use the control chart only when the side received the maximum of 5 actions. With results of 3 or 4 actions, all units would remain fully under control; only when a 5-action half-bound occurred, would there be the possibility that units would break free.

The victory conditions in the game were too hazy, and, as I mentioned before, the battle just went on and on.

I had given each division a number of points equal to the number of brigades in the command. Points were lost (a) when a brigade failed a morale test and fell back, and (b) when a side lost a melee. When the number of points initially assigned to a division were reduced to zero, then one brigade in the division had to be removed from the field. From this point on, each additional morale failure or lost melee resulted in yet another brigade being removed. Gradual removal of brigades just didn't work; the sides didn't attrit each other that much.

But I must mention one aspect of the attrition process that fatally affected the Union cause. This concerned the fact that during the firing and melee procedures, stands that were hit were not immediately defined as killed... instead, they were removed to the "Rally Zone".

Each half bound, both sides looked at the stands piled up in their Rally Zones, divided them into groups of 5 stands each, and used the following chart for each group: --------------------------- All 5 stands killed 70 --------------------------- 2 stands will rally, All others killed 35 --------------------------- All stands are rallied ---------------------------

Stands that rallied were permitted to rejoin their units. Thus a dice toss of under 35 meant that all 5 stands went back on the field. A toss of over 70 meant the ultimate disaster... everyone died.

I forget the exact numbers, but during the Union rallying dice throws, some 10 out of 12 percentage dice tosses turned out to exceed 70, and the entire rallying group of 5 stands went kerplunk!, and died on the spot.

That's 50 - count 'em - 50 stands lost, a huge portion of the Union force. Statistically improbable. But obviously not impossible.

In the game, I commanded the Union left flank, and succeeded in wiping out all my troops... in part, because of the horrible dice throws that occurred during the rallying phases, and in part, because I tossed poorly during melee resolution.

Melee consisted of two subphases. The first was what I termed the overrun phase. Here, immediately upon contact, the attacking and defending units determined if either lost a stand due to the initial shock of impact.

The sides added together the number of the stands involved in the initial contact of the lead units. Assume, for example, that the number of Confederate stands was "C", and the number of Union stands was "U", then the probability, P, that the Union lost a stand was:

- P = C/(U+C) while,

for the Confederates: P=U/(U+C)

To see what the numbers actually mean, in our battle, John Shirey's Confederate cavalry broke through to my Union artillery positions, and converged on a 1-stand Union battery. John's cavalry was composed of 7 stands, hence the values to be used in the overrun calculation were:

- C = 7, and U = 1

and the probability of the Union losing a stand was:

- P = 7/(7 + 1) or 87 percent

while the probability of the cavalry losing a stand was:

P = 1/(7 + 1) or 12 percent

The above figures meant that, most of the time, my 1-stand artillery battery would immediately be wiped out in the initial overrun... there'd be no second phase of melee to consider.

Note that if both of the contacting units were equal in size, the chance of either side losing a stand to the overrun procedures was 50 percent.

If the second melee subphase took place, then each stand on each side was valued at a certain number of points, the points were totaled, and every 10 points yielded a 10-sided Hit Die. A toss of 1,2,3,4 on the Hit Die sent one opposing stand to the Rally Zone. Prior to the assignment of Hit Dice, both sides attempted to bring up reinforcing units to assist the lead units placed in contact. This was a function of the brigadier.

Each brigadier diced to see how far he could travel to bring in reinforcements... the result was either 20, 30 or 40 inches. Then off rode the brigadier, waving his hat, calling on the support units.

He'd reach the first, and had an 80 percent chance to convince it to dash over to assist. If he failed, the unit would lose one stand to the Rally Zone. If he succeeded, he'd escort the unit back to the melee and ride to a second unit.

Each time the brigadier contacted a potential supporting unit, he'd subtract, from his initial travel distance allowance, the number of inches he had to ride to (a) reach the unit, and (b) escort it to the melee.

This meant that his initial allotment of 20, 30 or 40 inches was used up fairly rapidly... he couldn't contact as many units as he'd like.

The other damping factor on the procedure was the potential loss of a stand to the Rallying Zone if he failed to convince a unit (80 percent chance of success) to assist.

All in All

In all, the affair constituted one of better ACW games, and about the only topic of discussion during our post-game session was the application of the IPT methodology to the ACW era.

One interesting sidelight was that when units got out of control and advanced up the field at increased speed, they were given negative modifiers during the fire and melee phases. In other words, out-of-control units fired and fought less effectively than unit remaining under control.

This was in contrast to the situation set up in an ancients encounter we had fought several weeks earlier. Here, when units ran forward, uncontrolled, they received bonuses in melee.

In the ancients game, therefore, the players wanted their units to advance in an uncontrolled manner, while in the ACW game, they wanted to maintain control.

This difference in approaches wasn't mentioned by any of the players except in passing; no negative comments were made on the subject. Evidently, they found nothing wrong with the reversal of roles. Which brings up the subject of exactly how the concerned units should be treated... should it vary from era to era?

All of which says the system can be played either way. You pays your money an' you takes your choice.

Back to PW Review February 1995 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com