At the commencement of most of our highly coordinated, well planned, and cleverly organized PW meetings, some 25 members sit around the perimeter of the room, twiddling thumbs (two each), contemplating navels (one each), cleaning their fingernails (ten each) and muttering: "Didn't anyone bring any troops?"

This air of utter hopelessness lasts until some bright soul, more farseeing than the rest, enters the room with a box of toy soldiers, sets up a table or so, shakes out a green sheet, and announces: "Anyone wanna play?"

At the July meeting, there were two or three such clever souls, and he on whom this article concentrates is Ed Hyland, who appeared with his son Chris, both lugging their 15mm Napoleonic armies.

In response to his "Anyone wanna play?", Ed got some six volunteers, I among them. Along with the other comatose members, I had counted my navel about 22 times (still one each), twiddled my thumbs into ringlets... I was ready to play anything.

IMPERIAL GUARD (IG) is an antiquated set of rules; the first edition published, I think, in the early seventies (my copy of the second edition is dated 1976), and both editions, to my mind, are of like ilk: silly. The second in no way improved upon the first.

We set out our troops... I commanded the French right flank, advancing upon the thin British line under the control of Fred Haub.

Six stands comprise a battalion, and I had a light brigade of four battalions, whose troops were capable of forming in open order, Backing my lights were four squadrons of lancers, each of four stands. Both the infantry and cavalry were given a supporting battery.

Each turn, the sides dice for initiative, the French adding +1 to their die to indicate they are ever-so-much-more aggressive than their opponents.

Each bound consists of six phases, each with a distinct function; the side with initiative always performs whatever particular function is associated with the phase before his opponent. The phases are:

- 1. Change formation

2. Artillery fire

3. 1st movement plus charges to contact

4. Melee and musketry

5. 2nd movement

6. Rally routing troops

This last phase is the best: if a unit doesn't pass its morale test, it flees the field and goes home.

Movement is given in centimeters (no one knows why, even though the rules state: "...centimeters (...are...) the ideal measurement for 15mm..."], but what it amounts to is a movement of 6 inches for an infantry column, about 4 inches for an infantry line, and around 8 inches for cavalry.

Because of the phased sequence, the game needs an umpire to keep track of who's doing what to whom, and where everyone is in the sequence. Even so, and even with Ed Hyland at the helm (an old Napoleonic expression) , I believe we French were "gypped" of a phase of artillery fire at the beginning of the game. That's probably why we lost.

IG's weak point is its charts. There are charts, charts, charts and charts. And then there are more charts.

IG has the usual run of recognizeable patternry of the Napoleonic era... there are provisions for skirmishers and squares and canister and rifles and French assault columns and British lines, etc. And in addition to these, it has more gloss and gilt built in because each unit is typified according to the author's assessment of its ability -- French line, French Guards, French lights, British Guards, British line, this cavalry, that cavalry, and many more classes of troops. And each of these different troop classifications requires, in effect, a separate chart for firing, melee, etc.

Rather than setting up one generalized chart for all troops, and then have dice-tossing modifiers to differentiate amongst the capabilities of the units on the field, the authors distinguished between the troops by generating a huge series of charts.

This is all quite historically realistic and wonderfully accurate, but it certainly holds up the game, as all at table- side wait for the umpire to call out their particular unit characteristics in fire and melee.

A positive aspect is that, despite the wait-for-the-umpire delays, the sequence itself flows nicely, and the game proceeds at a good pace.

But the sequence gives rise to an anomaly or two.

Example 1: Note that in Phase 1, all units change formation, and that a phase or so later, in Phase 3, they charge to contact. The authors, however, decided that if cavalry charge infantry who didn't form square in Phase 1, they'd give the infantry yet another chance to do so in Phase 3. And so, we have a sort of "hasty reaction" built in, despite the setaside of a specific change-of-formation phase.

Example 2: If the active side's cavalry charge non-active cavalry in Phase 3, the target cavalry are "caught standing"-,- .. they cannot countercharge, nor change formation. During our game, the situation occurred wherein a cavalry unit charged another, and caught the target cavalry unit while it was still in column.

The thought was that if the authors provided a "hasty reaction" for infantry being charged, permitting the infantry to attempt to form square, they perhaps should have done so for cavalry.

Example 3: Note that there's a second movement capability in Phase 5 for units who didn't melee or do anything too strenuous during the previous phases. Which means that I can advance my infantry, in line, with absolute impunity, right up to (a teeny- weeny centimeter away) formed enemy cavalry.

Why? Because in the very first phase of the next bound, I'm guaranteed a change-of-formation phase, wherein my troops can form square. And this change of formation occurs before the opposing cavalry can charge on Phase 3 of the next bound.

I wrote an article on IG way back circa 1980, when I was first introduced to the game, and I mentioned the above three items. At the time, I was told that the rules-writers were "working on it", and that subsequent editions would correct any problems. Alas, there were no subsequent editions, and, in our game, Ed Hyland directed his scenario straight from the book.

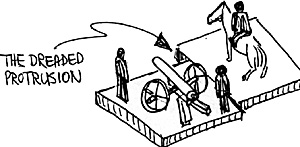

I must admit that Ed ran a tight ship (another Napoleonic bit of terminology) and kept close watch on the proceedings. For example, in the sketch below, our battery wanted to f ire canister at the British, but Ed forbade it.

The problem, said Ed, was that a cavalry stand, just to the right

of the artillery stand, protruded just an itsy-bitsy, teensy-weensy

bit beyond the artillery stand. The canister zone, extending 45

degrees to either side of center, would therefore intersect the

cavalry stand and IG forbids one to canister his own troops.

The problem, said Ed, was that a cavalry stand, just to the right

of the artillery stand, protruded just an itsy-bitsy, teensy-weensy

bit beyond the artillery stand. The canister zone, extending 45

degrees to either side of center, would therefore intersect the

cavalry stand and IG forbids one to canister his own troops.

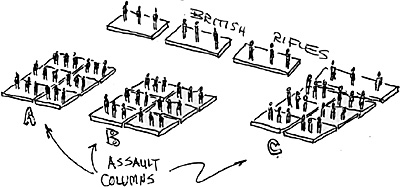

IG rules show their age in their rigidity. For example, in the sketch below, taken from our game, note that French Assault Column C has contacted a line of British rif les during Phase 3 of the sequence.

Assault Columns A and B didn't quite make it into contact, and hang back about an inch.

Immediately after Phase 3 is the fire phase, Phase 4, and

the Rifles get to blast away.

Immediately after Phase 3 is the fire phase, Phase 4, and

the Rifles get to blast away.

Assault Column C and the Rifles are defined as being "in contact", and while the Rifles are permitted to fire defensively at the unit contacting them, they cannot fire at Columns A or B, nor can Columns A and B fire at the Rifles. All of which, because of the configuration of the units, seems rather strange.

This problem arises because of the layout of the IG charts, which permit a unit to fire only as a single entity and only at a single target.

British General Haub had set out his Rifles and one other unit of light troops in advance of his main line. These two battalions managed to hold up three French brigades.

There is no provision in IG for some sort of automatic fall- back when an advancing formed unit contacts an enemy line deployed in skirmish order. The oncoming unit must duke it out with the open order lights, and, in our case, the Brits did quite well.

My 1994 exposure to IG didn't change my 1980 opinion of the rules; perhaps I'll try them again, circa 2000.

Back to PW Review August 1994 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com