Arty Conliff's current set of rules, ARMATI, appeared at HISTORICON in July. The rules book is 43 pages long, with 11 of them devoted to the requisite "army" lists.

Unlike the previous glossy Conliffe effort (TACTICA), the booklet is in black and white; the only colored item is the cover itself.

Tom Elsworth paid me a visit after HISTORICON, and he and I and Jeff Wiltrout engaged in some 5 battles, both 25mm and 15mm.

Normal, everyday, good ol' American inches are not used for measurement in the ARMATI scheme of things; one must use what may be termed an "Arty Conliffe Inch (ACI)" drawings of which are given in the back of the rules book. The book instructs the gamer to xerox the ACI rulers, cut them out, and use them for measurement.

Depending upon the number of figures a player wants to place on the field, ARMATI gives the player the choice of setting up a game in 3 different scales - none of which are really defined -- and because of this flexibility in the size of units, and the components of the units (number of stands), and their allowed configurations, the movement and firing distances change from set-up to set-up, hence the need for the different ACI's.

For example, using the most compact scale in 25mm (what is termed the Intro Scheme, wherein all units consist solely of a single stand) the compressed ACI turns out to be a half-inch. In other words, when your unit moves 6 inches forward, then, using the compressed ACI ruler, it's really moving 3 inches.

Other ACI rulers are given, definitely a helpful gaming aid, since the player has no need to do his own conversion from scale to scale, but merely to pick up the appropriate ACI ruler.

In terms of its definitions of unit sizes, ARMATI is similar to DBA/DBM, wherein an "element", i.e., a unit, is never defined, and the author authoritatively tells you that your army, your force, will consist of so-many elements, of such-and-such a size, and please don't argue about it.

The number of figures per stand is unimportant, other than to visually give an indication of the type of unit represented. Each type has a Break Point (BP), meaning that when the unit receives a number of hits equal to its Break Point, it's removed from the battle. For example, the BP for light cavalry units is 2, while for heavy infantry, it is 4.

Unlike TACTICA, therefore, casualties are not noted in terms of so many figures per unit.

For example, regardless of scale, regardless of the number of figures within a heavy infantry unit, it breaks after 4 hits.

Nor are casualties inflicted on an opponent as a function of the number of figures per inflicting unit. Melee is determined by a consideration. of unit type-versus -type, and high die roll (6-sided die) scores a hit on the enemy.

For example, cataphracts have a frontal impact factor of +6, while light infantry have a factor of 4. The cataphracts, therefore, add +6 to their roll, the light infantry add +4, and the high total will score on the other.

The frontal impact factors of the various unit types within the listed armies are interesting, witness, for example:

- +7 for Alexandrian

phalanx

+4 for Alexander's light infantry

+4 for Alexander's heavy cavalry

Conliffe states, on page 27, that it was he, himself, who generated the relative combat values:

- ...since "final word" research on every

troop type is often tough to find, my own

"gut feeling" about how a unit should fight

contributes to its game attributes...

The values I've quoted above are the frontal impact factors; each unit is also given flank and rear factors. Representative values for several units are:

| Unit | Front | Flank | Rear |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexandrian phalanx | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Cataphracts | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Light infantry | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Slingers | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Note that it's impossible to "sneak up" on light infantry; they fight in all directions. Ditto for slingers. In contrast, hitting the flank of the phalanx is devastating, since their impact factor (die roll modifier) becomes zero.

Once contact between two units is made, life for both units becomes miserable, for both will remain in contact, without moving, in the same configuration, until one or the other dies. Depending upon the dice tosses, therefore, units may remain locked in combat for several bounds, until one of them reaches its Break Point in terms of the hits it receives.

This is one of my few peeves about ARMATI... I'm a single- bound melee-man. Let a unit charge forward, I sez, let it smack away at its opponent, and if it doesn't make a dent, let it fall back. Let's not have any of these "forever melees".

The ARMATI sequence is an alternating one, wherein the side with initiative has the choice of moving first or second. Each army in the lists is given an Initiative Factor, which it adds to its die roll (6- sided)... for example, in our battle between the army of Alexander the Great and that of the Indian army of Porus the Not-So-Great, Alexander always added +2 to his initiative roll... Porus didn't get to win the initiative too many times.

The first phase in the sequence deals with firing... bows, slings, javelins, etc. Here, the firing unit tosses a die, and this is compared with a modified die roll of the target unit. The target unit's die is augmented by a Protection Factor, PROT, and the interesting thing about PROT is that it's a constant, regardless of the direction from which arrows, javelins, rocks, etc., come.

For example, a Greek phalanx has a PROT of +2. Shoot at them from the front... it's +2. Shoot at them from the flank... it's +2. Shoot at them from the rear... it's +2. Light cavalry have a PROT of +1. This is a wee bit different from the WRG approach, which takes into account the "shielded and unshielded" sides of the target.

Hits received during the firing phase count toward the target unit's BP... enough of them and the unit disappears.

Next in the sequence, after firing, is the movement phase for one side, and if contact is made, melee is resolved immediately. After this, the other side moves and makes contact.

During the movement phase, if a unit remains immobile, it can attempt to rally, to remove one of its BP markers. This done with a toss of 5 or 6. If the general himself runs over to lend a hand, the required toss is 4, 5, or 6.

In 25mm scale, heavy cavalry movement is given as 15 inches, light

cavalry 15 inches, light infantry 9, and heavy infantry move 6

inches. One might think, therefore, that ARMATI is a quick moving

game, with units able to dash all over the place, all of the time.

Not so.

In 25mm scale, heavy cavalry movement is given as 15 inches, light

cavalry 15 inches, light infantry 9, and heavy infantry move 6

inches. One might think, therefore, that ARMATI is a quick moving

game, with units able to dash all over the place, all of the time.

Not so.

First, using the ACI rulers, units may not move a "real" 15 inches on the table as you push them forward for 15 ACI inches. Depending upon the scale, the 15 inch move may actually be reduced to 5 or 7 or 10 "real" inches.

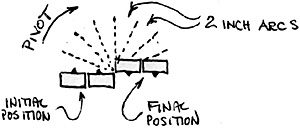

A second factor that slows down the whole process are the wheeling restrictions. For example, heavy infantry cannot wheel and move in the same bound. They can wheel 2 inches... and that's it. The unit is permitted to move no further that turn. One corner of the frontage of the unit remains stationary as a reference, the other pivots 2 inches around the reference corner, and the unit halts. The book lists four exceptions to the "wheel and halt" rule, among them Roman Cohorts and Carthaginian African Veterans... these can wheel and continue to move. Carthaginian Veterans?

In 25mm, the ARMATI frontage is defined as 60mm, or close to 2.5 inches. Two stands, side by side, thus cover a 5 inch frontage. In the diagram below, note that such a 2-stand unit, in attempting to make a 180 degree turn, requires 8 turns to do so. Each pivot can encompass no more than a 2-inch wheel, and to turn the, full 180 degrees, an arc of 16 inches must be traversed.

ARMATI restricts all wheels of all units, regardless of type, to a maximum, per turn, of 2 inches. This includes, not only the heavy units, but all light infantry, skirmish units and light cavalry. These lighter units are granted an exception - if it is an exception - in that they are permitted to do an immediate aboutface and dash off.

In one of our games, I placed 3 heavy cavalry units, each of 2 stands, side by side, producing a total frontage of some 15 inches.

This was a mistake, for I now found myself with an absolutely unwieldy, completely unmaneuverable unit, able to move in one direction only... forward. I tried to perform a turn to the right and, at battle's end, some 8 turns later, had only just started. A 15-inch frontage results in an arc of 47 inches in trying to turn a full 180 degrees. When divided into 2-inch wheeling increments, the unit thus requires a total of 23 separate increments, separate gaming turns, to shift 180 degrees.

A 2-inch wheel doesn't allow for too much pivoting, and consequently, once a unit is assigned a facing direction, it pretty much remains looking in that direction, and only slowly, 2-inches by 2-inches by 2-inches by 2-inches, does it turn to a newly assigned direction. Even light cavalry units take quite a bit of maneuvering to change direction.

The dreaded 2-inch-wheel restriction is my second peeve about ARMATI... I'm a free-wheeling man. Let a unit wheel in place 90 degrees per turn, sez I, in fact, let it do multiple pirouettes in place about its pivot point... let's keep the game going.

Watching an ARMATI player move his troops... pivot-2-inches and move forward, pivot-2-inches and move forward, etc... one is reminded of a DBM game with its micro-inch measurement requirements. The picayunish measurements of DBA, DBM and the entire WRG series is one reason I stay away from them.

I realize that phalanxes shouldn't be allowed to zip around corners, but the 2-inch-wheel restriction imposed on all units took some of the enjoyment out of the game for me.

But that said, I must admit that we spent some interesting hours in our investigation of the* rules. As you read the rule book and come to a particular point, you wonder "Now why did Conliffe do that?"

And, in most cases, you find out. The game is nicely balanced. The relative immobility of heavy units, and their incapability of going anywhere except forward, is compensated for by their ability to crush an enemy unit on contact.

A listing of unit types -- heavy cavalry, chariots, elephants, etc. -- indicates those which are given "impetus" on contact. These units, if they win the initial round of melee, instead of merely inflicting a single Break Point marker against an opponent, inflict several, and break the opponent immediately.

Another interesting ploy involves the command capabilities of the various armies listed in the rules.

Under the DBA/DBM rules, one tosses a 6-sided die, and one moves a number of groups of stands on the field equal to the number of pips tossed. Groups in "excess" of the number tossed remain immobile.

ARMATI, too, imposes a restriction on the number of units that may move. But, unlike DBM, it doesn't vary from turn to turn according to the whim of a die roll. Each listed force is given a specific number of "heavy groups" and "light groups" representing, in the eyes of the author, the number of groups which the commander of the force is capable of handling.

For example, Alexander can control 4 heavy groups and 5 light groups. In the Alexandrian army are 8 heavy units, and 8 light units. This means that Alexander must take his 8 heavy units and group them into no more than 4 blocks, where a block is termed a "division" (a block can consist of a single unit) . Similarly, he must group his 8 light units into a maximum of 5 divisions.

In contrast, take the listing for a Late Acheamenidian army: here, the commander must group a total of 10 heavy units into no more than 3 blocks, 3 divisions, and a total of 6 light units into no more than 4 divisions.

The result is that Alexander has a fairly flexible heavy contingent, whereas the Acheamenidian commander is forced into several huge, klunky blocks for his heavies.

Once a division is formed, it is permanent... the units comprising the block will remain with the division for the remainder of the battle. And thereby hangs the "generalship" of the commander at the beginning of the battle. How he divides his units into divisions severely affects the ability of the force.

When our Indian army under Porus fought Alexander's army, Porus was given a mix of 11 heavy units (infantry, cavalry, elephants) which had to be broken into no more than 3 heavy divisions.

Five of the heavy infantry were also bowmen, and we chose not to place these units in a controlled division. They were assigned to defend a hill, and on the hill they stood, and stood, and stood... not being in one of the 3 controlled divisions, these units were not permitted to move for the remainder of the battle.

Porus' remaining 6 heavy units were divided into 3 heavy divisions, giving us a wee bit of mobility. A wee, wee bit.

ARMATI does have a procedure for breaking off a part of a division so that the force has more than its initial "authorized" number of controlled blocks. After a contact is made between two divisions, a portion of the division not in contact with the enemy may break away from its parent division.

This is not without a penalty, however, for the side then loses 2 of its Initiative Points, and, consequently, may suffer later in the sequence.

As a gaming ploy, the creation of a block assignment of a number of controlled divisions is an excellent one. Whether or not it truly creates the command and control problems of yesteryear is another issue. But there's just as much logic behind it and it's definitely just as good as, if not better than, the DBA/DBM pip assignment.

I can see a number of gamers vehemently objecting to the requirement to assign their units, supposedly independent, into a limited number of commands, or else suffer the penalty of having them rendered completely immobile for the entire battle.

In a sense, for some armies, even if all units are assigned to a controlled block, the size of the division may get out of hand, and the block may become- so unwieldy (its only possible movement is forward) that you'll find you won't move it anyway... since, if you do go forward, you expose your flanks with no way for the unit, on its own, to protect itself.

The current evolution of ancients gaming rules, with TACTICA, DBA/DBM, and now, ARMATI, is fascinating to see. It appears that the trend - if these three gaming structures can be said to constitute a trend - is toward focusing on battleline movement and engagement, rather than the nitty-gritty, unit-versus-unit, weapons' comparison matrices.

I favor the ARMATI approach, the broad picture... I'm a broad picture man. For years, I've tried to assess the relative merits of weaponry... if halberds against swords rate a +3, then what do assegais against bayonets rate? ... or maces against pikes?? ARMATI essentially bypasses these weighty issues....more. power to it.

Back to PW Review August 1994 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com