In truth, the Union didn't attack at dawn, they attacked around

lunch-hour at Ian Weekly's home. Ian invited us over for our yearly Weekly game, or our Weekly yearly game... I'm never sure which. When photographing his models for his magazine articles, Ian suitably spices the pictures with a number of 30mm Willy/Suren figures from his inventory. He's now amassed a good-sized collection of beautifully detailed Willy 30mm figures of all eras... two years ago, he set up a Napoleonics game, and last year, we played a Renaissance game with some superbly painted landsknechts et al. This year, Ian had commissioned Don Lambert to paint a number of Suren American Civil War figures, and for our Weekly scenario, he had set up a Union attack on a Confederate outpost.

Ian furnished the figures and terrain, and I furnished the rules. After the requisite amount of detailed research into the era (three minutes), in-depth analysis of the organization of force structure (two minutes), study of the weapons capabilities of the period (one minute), investigation of the type of sequence that would most realistically and accurately portray the era of interest (two minutes), I jotted down the rules (three minutes).

Now some people would say that a total of eleven minutes to note down a set of rules is far too long (I have heard that Arty Conliffe took some five minutes to write TACTICA, Phil Barker three minutes to write DBA, and Bob Coggins about two minutes to write NAPOLEON'S BATTLES), but the reason I took so long was that I purposely stretched out the pre-game period prior to lunch, waiting for Ian to produce his world-famous egg salad sandwiches.

I'm not sure just what he puts in these sandwiches, but they're definitely worth a trip to England in and of themselves.

But now, to action. In the encounter, the Union had three advancing "regiments" ranging from 6 to 8 figures each, plus cavalry, plus 3 guns (which came in around the third turn).

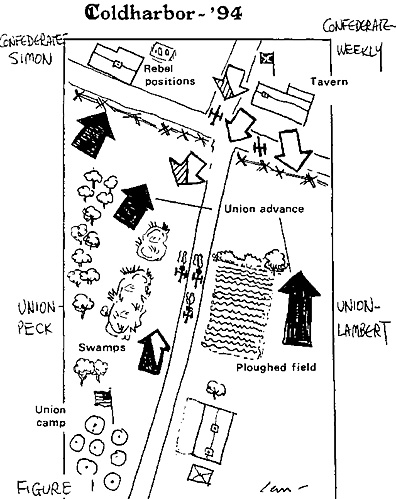

Figure 1 is a sketch of the battlefield, drawn by Ian himself.

We defending Confederates (Ian and I) had two regiments of some 5 men each, a cavalry unit, and 2 guns. All of our troops, while located in an enclosed area, were not set up, but had to move forward to man the defensive lines.

On the very first turn, Robin Peck, Union Commander of the Army of Buxton, launched his cavalry straight toward our lines, hoping to catch us before we could reach our defensive positions. In retrospect, this was not a bad deal, for if he caught us undeployed, the battle would quickly end.

Each turn, the active side commenced with 2 "actions" assigned to each unit. An action permitted a unit to advance, wheel, or, if a unit wanted to change formation, an action contributed 30% towards its success. In other words, if one action was devoted to changing formation, there would be 30% chance of doing so; if 2 actions were so devoted, the chance was 60%, while 3 actions gave rise to 90%.

The initial 2 actions assigned to the units were a base to which others could be added; the active side diced for each brigade to see if any more actions were available. This was a function of the force commander's Military Capability (ML), which could be either 60%, 70$ or 80%. If, for example, the ML was 70, the chance of receiving additional actions looked like:

- Chart 1

---------------------------------------

No additional actions

ML = 70 ---------------------------------------

Brigade receives 1 add'l action

1/2 ML = 35---------------------------------------

Brigade receives 3 add'l actions

---------------------------------------

Thus a toss of percentage dice of, say, 52, and the brigade received 1 additional action which could be assigned to any of its units to augment its original base of 2 actions.

Cavalry advanced 6 inches per action, infantry 4 inches. As the Union cavalry charged forward, we Confederates, on our active half of the turn, diced for additional actions, and on 2 consecutive turns, our artillery units were lucky enough to receive 3 additional ones. These were quickly assigned to our artillery pieces, which we trundled up, unlimbered, and commenced to fire.

A couple of good shots and the oncoming Union cavalry changed its mind about the charge and fled.

The fire and movement phases were independent of one another; the basic sequence consisted of 8 steps:

- Union move

Both sides fire

Resolve melee

Union rally its troops

Confederate move

Both sides fire

Resolve melee

Confederates rally their troops

Note there were two fire phases during the bound, during which each side got to pop away at the other. Each side was given a deck of 6 Fire Cards, with the cards annotated with instructions such as "1 unit fires", or "3 units fire", or "All units fire at half effect", etc. These cards were randomly shuffled.

When a fire phase arrived, both sides contributed a number of these cards (dealt randomly) to a common deck. The number of cards contributed was a function of the commander's Military Capability (ML), previously discussed. Using the ML of 70% as an example again, the result looked like:

Chart 2

---------------------------------------

Contribute 2 cards

ML = 70 ---------------------------------------

Contribute 3 cards

1/2 ML = 35 ---------------------------------------

Contribute 4 cards

---------------------------------------

When a side's card was drawn from the common deck, the particular number of units noted on the card could fire. Thus it was possible that one side could contribute 2 cards to the common deck, while the other could contribute 4 cards, indicating that, statistically speaking, as the common deck cards were drawn, the "4 side" should outshoot the "2 side".

But in addition to the cards contributed by the sides, there was one other placed in the common deck... a card labeled "End of Fire Phase". When this was drawn, firing was complete for that half bound, and all cards returned to their owners.

This meant that if, after randomly drawing, say, 2 of one side's cards, the "End" card popped up, the opposing side wouldn't even get to aim its muskets. Or, an even more horrendous event was that the "End" card could be the first one drawn, indicating that the entire fire phase was nulled, that neither side fired.

Each man in a regiment contributed 10% to the Total Fire Power (TFP) of his unit, and a gun fired with the equivalency of a 5 man regiment, thus giving it a TFP of 50%. When the gun fired, the fire result chart looked like:

- Chart 3

---------------------------------------

No effect

TFP = 50 ---------------------------------------

1 man to the Rally Zone

1/2 TFP = 25 ---------------------------------------

1 man killed

---------------------------------------

The "Rally Zone" referred to in the chart is a sort of limbo land in which men are taken off the field and salted away until they are rallied. Supposedly, this is a representation of men who become rattled and ineffective under fire, and are of no use to their unit until the commander, during the rally phase, comes riding by, giving them the ol' John Wayne cry of "Your country needs you!", or "The fate of the nation is in your hands!", and similar blather.

Note in the sequence as listed, that each side gets to rally its troops once per bound. Here, too, the force commander plays a role. He is placed with a unit, and there is a 70% chance that the commander rallies a man. He may then rally a second at a 60% chance, a third at a 50% chance, and so on.

And now, back to the scenario. As I indicated, our Confederate guns quickly put an end to the Union cavalry charge. While this was going on, the Union infantry were advancing, but due to some poor dice tossing, advancing at a snail's pace.

The Union brigade on the Union right flank, composed of two regiments, each time it tossed for additional movement actions on Chart 1, received none. The regiments thus had to make due with their 2 original actions, advancing only 8 inches (4 inches per action) each turn.

And they were further held up by their inability to deploy. For a couple of turns, each regiment devoted its 2 actions to deploying (instead of moving forward), giving them a 60% chance to change formation. No luck, and the entire Union right flank came to a halt.

The Yankee left flank did much better... during one of the fire phases, having been hit by Union fire, the defending Confederate unit took a morale test, failed, and fell back, leaving the defenses unmanned. Up came a Union regiment and took control of that side of the field.

With their left flank in hand, the Union could have rapidly overpowered the Southern defenses despite the slowness of their right flank units to advance. I say "could have", because they now brought up three guns to midfield, unlimbered, and prepared to batter our Rebel forces.

'Twas then that the Union general staff of General Peck flubbed de dub. As the Union guns were set in place and unlimbered, I asked General Peck as to what he thought a good arc of fire would be for the artillery pieces, i.e., should guns hit anything in the zone 45 degrees off their center line, or 22 degrees, etc.

The previous three days, General Robin Peck and I had been playing an assortment of DBA and DBM games, and Robin was now well steeped in WRG procedures. In the DBA and DBM scheme of things, movements are teeny-weeny, measured in centimeters and microinches, and firing ranges, accordingly, are also teeny-weeny. Hence these rules sets, instead of giving an arc of fire in terms of degrees, use an arc of fire equal to "one stand width to either side".

And so, Robin, completely overcome by the historically realistic and natural logic inherent in the DBA and DBM rules systems, stated that, here, too, in our game, the zone of fire of the artillery pieces should be measured by "one stand width to either side".

Alas! This key decision of the Union General Staff completely emasculated the 3 Union batteries. Instead of commanding the entire field before them, they now could fire only along a narrow strip along which the gun was actually pointing; in effect, they actually had to "point" at a given target to produce an impact on it.

A turn or so later, out charged our Confederate cavalry to contact the advancing Yankee troops. The Yanks held firm, and our horsemen were beaten back, but I noted that if it wasn't for the "one stand width" rule restricting artillery fire, the Confederate cavalry wouldn't even had reached their target but would have easily been wiped out as soon as they left the Confederate lines.

I should note that the rule also restricted our Southern batteries, but in far less a manner than those of the Union. No matter where our guns pointed, there seemed to be a Yankee unit, so we didn't have to continuously swivel our batteries as much as did the Northern commanders.

At battle's end, we Confederate commanders were definitely hurting, and we gallantly offered the Unionists our swords. What was interesting was that the Union commanders were hurting also, and it was only with difficulty that we persuaded them to acknowledge victory.

The rules system was fairly simple; about the only new procedure introduced was that concerning the use of the fire deck cards. We Confederates, outnumbered and playing defensively, welcomed the advent of the fire phases much more so than did the advancing Union troops. On several bounds, however, we were caught short in the fire phase, as the first card drawn, denoting which side fired first, turned out to be the "End" card, indicating that there would be no fire phase at all!

Since there are two fire phases in each bound, each giving both sides the opportunity to fire, drawing an "End" card, completely nulling the fire phase, didn't produce as devastating a result as it would have in other rules sets wherein a side gets to fire only once per bound.

In melee, each man contributed combat points, and the total points involved were set out to derive a combat results chart similar to that of Chart 3, the basic fire chart. Here, too, men were either sent to the Rally Zone, to be rounded up later, or were permanently removed from the game.

As for the charts themselves, an examination of Charts 1 through 3 shows that once you've seen one chart, you've seen 'em all... they're all patterned the same. A reference value is selected, and if the throw of percentage dice is below half this reference level, good things happen to you, while if you toss above the reference, nothing happens.

Back to PW Review April/May 1994 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com