It was a "ship game". I had taken my bandsaw and cut out a number of 4-inch long Monitors and Merrimacs and assorted American Civil War paddlewheelers.

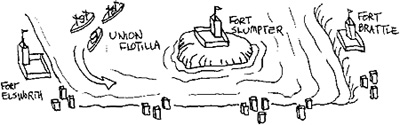

The scenario looked at:

- a. A southern harbor, on the perimeter of which were several small Confederate towns.

b. Three forts commanding the harbor entrance.

c. 4 Confederate warships in port.

d. 3 berthed Confederate merchantships.

e. A flotilla of 8 Union ships about to enter the harbor, and wreak havoc on the Confederates.

The scenario was played about four times, each time varying the geography of the port, the rules, the number of ships, etc. I discovered it was exceedingly difficult to strike a balance between the two forces.

The sides were assigned victory points for enemy ships destroyed, and the Union was given additional points for bashing the Confederate merchantmen, shelling the towns, and knocking out the guns in the defending forts.

After one or two plays, the best Union strategy became evident: enter the harbor, which encompassed the entire ping-pong table, sticking to one side of the harbor, knock out the fort on that side, and proceed to sail along the inner shore, blastinq the towns and merchantmen.

Cap'ns Cliff Sayre and Don Lambert were the Union commanders; Jim Butters and I defended the Confederate assets. In this particular set-up, I had erred in having the Southern side toss dice for the number of guns in each fort.

Although the oncoming Union commanders didn't know this at first, it turned out that Forts Elsworth and Brattle had one battery each, while Fort Slumpter, in the middle of the bay, had three. What I should have done was place three batteries in each fort.

In this particular set of naval rules, each ship and each fort had its own data sheet. Unlike the rules of other, more mundane authors, there were no "hull boxes" to be crossed out. Instead, innovative fellow that I am, I set up a number of "hull columns". It becomes immediately obvious to the connoisseur of naval games that hull columns are vastly different from, and superior to, hull boxes.

| NAME | TYPE OF SHIP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAMAGE COLUMN | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| NO 1 Gun | NO 2 Gun | NO 3

Gun | PORT | STBD | ENGINES | WHEEL HOUSE | HULL |

| O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| Fort | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NO 1 Gun | NO 2 Gun | NO 3

Gun | FORT Magazine |

| O | O | O | O |

| O | O | O | O |

| O | O | O | O |

| O | O | O | O |

Above are typical data sheets for the ships and the forts. The firing procedure required two dice throws:

- a. Determination of whether or not the target was hit.

b. A second toss of a 10-sided die to determine the particular column that was affected (example: if the above ship was hit, then on a toss of a "4", count over, starting from the left, four columns, and cross out one box for the port engine).

On Turn #1, the Union fleet appeared as shown on the map, and fired its first barrage? broadside? volley? at Fort Elsworth. Cap'n Sayre, in the van, failed to get a hit.

I should note that there were 3 types of ships; it may be hard to believe, but they were classed as Type-1, Type-2, and Type-3.

A Type-2 ship, for example, used nothing but "2" modifiers:

- a. It could move 2 inches before turning 45 degrees.

b. It had two Type-2 guns.

c. Each Type-2 gun tossed two 10-sided dice when it fired.

d. Each Type-2 gun had a modifier of +2 added to the 10sided die roll when it fired.

For a Type 3 ship, simply substitute the number "3" in the above description whenever you see a "2". This means that on a Type-3 ship, for example, 3 dice were tossed for each of the 3 Type-3 guns firing, a total of 9 dice, providing quite a blast.

By definition, the guns in the forts were all Type-2's, since I thought that if they had been designated Type-3's, the Union wouldn't have stood a chance.

As the dice were tossed for each battery, a critical hit on the target was defined to occur if a pair of "8's" or "9's" or "10's" appeared. Note that under this definition, a Type-1 battery cannot obtain a critical hit, since its battery of one gun tosses only one die.

This placed the one-battery forts at a great disadvantage... not only were they fairly vulnerable (having only a single battery), but they could never inflict a critical hit on the Union ships. When the Union fleet entered the harbor, the Confederate ships sailed out to meet them, and in one of the first exchanges of fire, a critical hit was obtained on one of the Confederate craft.

The critical hit on the Confederate ship required a look-up on the Critical Hit Chart, on which were listed such penalties as: (a) cross out every box in every column, leaving only one box per column, or (b) ship is on fire (only 30% chance to put it out), or (c) cross out all boxes on one or two battery columns, and so on. None of the Critical Hit Chart results mandated that the target immediately blow up; each occurrence of damage was somewhat less than total destruction. It was my thought that with only a dozen or so tokens on each side, plus the myriad of dice tosses going on each turn, the game wouldn't last too long if critical hits were defined to be immediately fatal.

The Approach

As the Union ships approached, Confederate Cap'n Jim Butters started to move his merchantmen out to sea to escape the oncoming warships. The umpire, however, stayed Jim's hand.

"Why can't my ships move out to protect themselves?" asked Cap'n Jim.

I put my hand around Jim's shoulders: "Now, looky 'ere, mitey, an' gimme yer undivided 'tenshun... this 'ere's a ship gime, and yer crews is a-carousin' and a-wenchin' in town. Now, mitey, 'ow can they take their ship out of port?"

Faced with such devastating naval logic, Cap'n Jim had no rebuttal, and the merchantmen stayed were they were, doing what they were supposed to do, providing targets for the Union guns.

A turn or so later, and the Union ships had taken out Fort Elsworth, completely destroying its single battery. This meant that one side of the bay was open to the Union ships.

The sequence was an alternate one, and after each side's movement, there was a fire phase:

- a. Side A moves all craft

b. Draw a "Fire Card". The deck was composed of 6 cards, and on each was tabulated the type of battery (Type 1, 2 or 3), that could fire. All guns of the type designated, on both sides, fired simultaneously.

c. Side B moves all craft

d. Draw a Fire Card.

The Confederates were definitely at a disadvantage in this scenario. Not only were they outgunned, but they were out-diced. The Union seemed to score all the hits. When a battery fired and tossed its requisite number of 10-side Hit Dice, the following parameters were of interest:

- +D The die roll

+T The modifier for the type of gun (+1, +2, or +3)

-R The range modifier, obtained by taking the ten's digit of the range measurement (thus a range of 34 inches gave rise to a modifier of -3, a range of 57 inches produced a modifier of -5, etc.)

For each die tossed, one added D to T, subtracted R, and the result had to total 7 or better to score a hit.

And not only outgunned and out-diced, but it turned out the Southerners were out-rammed.

The Union had three ships capable of ramming, the Confederates only one. When the rammer rammed the rammee, not only did the rammee take damage, but so did the rammer.

Union Cap'n Cliff Sayre used his rammer to penetrate the sides of a Confederate ship, and we noted the damage to the target. Then I announced that the ramming ship itself would not escape unharmed; the damage to the ramming Union ship would be decided by a dice throw... either 1, 2 or 3 boxes crossed out on the rammer's data sheet, and that it was Cap'n Cliff's choice, as the owning player, of which boxes it was that should be crossed out on his ship.

This announcement produced an immediate series of boos and catcalls. "Unrealistic!" was amongst the worst. I must immediately inform the reader that there is nothing that strikes to the heart of a wargames author as a cry of "Unrealistic!", and I was deeply hurt by the sadistic insensitivity of the participants.

All present thought that the owning player should have no say in the determination of damage to his own ship.

But, alas!, this was not the only such cry of "Unrealistic!" heard in the game.

A turn or so later, and Cap'n Jim's Confederate rammer was on course, proceeding directly toward Cap'n Cliff's Union rammer, which was also proceeding directly toward Cap'n Jim's ship. The world held its breath as the two rammers built up speed.

In the alternate movement sequence, Cap'n Cliff lucked out... it was on his half of the turn that he was able to move his ship and contact the opposing craft.

The umpire immediately stated that Cap 'n Cliff's ship was a rammer, and Cap'n Jim's ship was a rammee. Which meant that Jim's ship took lottsa damage, while Cliff's ship only suffered a wee bit.

Again I heard that terrible cry of the wild: "Unrealistic!", and again I shivered my timbers.

Jim's protest was based on his assertion that, just as Cliff was trying to ram him, he was trying to ram Cliff, and so if the ships hit bow to bow, both should suffer equal damage.

Once again I put my arm around Jim's shoulders, and explained in my best Long John Silver manner: "Now, looky 'ere, mitey, this 'ere's a ship gime, and it uses an alternitey movement sequence. It's just o' turn o' bad luck that Cap'n Cliff rammed 'is ship into yor'n, instead o' vicey versey.

Jim protested no more, but I could see him silently mouth the words "Unrealistic! Unrealistic!" over and over again. In subsequent games (don't tell Jim this) , we corrected for the rammee/rammer problem, implementing Jim's suggestion.

Nothing Worked for the CSA

A full bound was defined as 20 minutes, and the battle, starting at 2:00 PM, was to last until dark at 6:00 PM, or 9 game turns, at which time we would add up victory points.

I mentioned before, nothing worked for the Confederates, and by the time 6:00 PM rolled around, 3 of the 4 Southern ships were sunk, their coastline towns were in flames, one Confederate merchantship had blown up, the forts were out of commission, and the happy Union flotilla commanders were about ready to wrap it up for the afternoon, and go home.

Even the point system proved to side with the Union. I had given the Union 3 victory points for every successful hit on the Confederate towns, and 3 points were way off the mark and out of line with a proper evaluation of the worth of a hit on a town.

In other games, 1 victory point seemed sufficient for a hit on a town, preventing an unbalanced set of victory conditions.

Back to PW Review April/May 1994 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com