UNION GENERAL LAMBERT WINS A GREAT VICTORY!

UNION GENERAL LAMBERT WINS A GREAT VICTORY!

Special to the REVIEW. Using an exciting new set of ACW rules, General Don Lambert smashed the Confederate forces at Buttcrack, Arkansas, several miles down the road from where our great President was born.

So overwhelming was General Lambert's victory that, it is rumored, the citizenry has approached him to persuade him to run for Congress. Whether or not the General wishes to use his talents in the political arena remains to be seen.

The great Lambert victory was achieved on the Simon ping-pong table using a plethora of 30mm ACW figures. So unusual were the rules that not a data sheet was to be seen... the only items on the field were those of the infantry, the artillery, the cavalry, the dice, and several score of flag- and pennant-bearing figures.

Each time a unit (a regiment of 4 stands) took a hit, it received a marker, a figure bearing a flag. Three such flags and one stand out of the four in the regiment was permanently removed. Although stands could not be recovered, it was possible to remove flags, thus reducing the possibility of losing another stand.

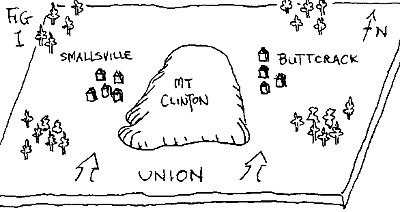

Figure 1 is a sketch of the field, indicating two key objectives of the Northern forces. On the western half of the table, there was Smallsville, and on the eastern half, Buttcrack. At the battle's beginning, Confederate units occupied both towns, and it was the Union mission to dislodge them.

We played the battle twice, and the first game resulted in an overwhelming Union victory. As it seemed like a good idea at the time, we decided to change sides and replay the battle. All the players switched, with the exception of the good General Lambert, who remained on the side of the Union. It was a wise decision for the staunch Unionist.

On the western half of the table, at Smallsville, the Simon federal forces, consisting of two brigades (a total of 6 regiments), attacked the Southerners in the town.

During the regular movement phases, units could approach no closer than 3 inches to enemy units. Then, on the melee phase, one unit was selected to close to contact. A sub-procedure then determined if other units were drawn into the combat. Melee was resolved.

The sequence for the bound had four basic phases, as described below.

- a. Side A moves and fires. The side dices for the number of actions assigned to each unit on its side, and proceeds to use them for either movement or firing.

b. Side A closes to contact, and resolves melees.

c. Side B moves and fires. Same as phase a.

d. Side A closes to contact. Same as phase c.

Given the above sequence, it is noticeable for its "gotcha" effect, for, as listed, the active side can fire and move and then close to contact for melee resolution without the opposition permitted to move a muscle.

To alleviate this one-sided situation, a series of pre-melee procedures allow the defensive side to react, preventing the active side from having everything his way.

There may be several pre-melee reaction and fire phases.

- i. When the active side moves, its units must end up no closer than 3 inches to any enemy unit. The active side then selects one unit and closes to contact.

ii. The defensive unit now has a 70% chance to react... either to fire or deploy. If caught in the flank, or in column, it may deploy if its dice throw is successful. If it is already deployed, it may fire. If it fires, the attacking unit takes a morale test to see if it stands. iii. Once the defensive unit dices and completes its actions, there is a 20% chance the pre-melee phases end. Percentage dice are tossed, and if the phases do end, melee is resolved.

iv. If the pre-melee phases continue, the initiative switches to the attacking unit; it has a 70% chance to fire. Whether successful or not, there is now a 40% chance that the pre-melee phases continue.

v. If the phases continue, it's now the defender's turn to either deploy (if he missed his deployment on the first round), or fire. Again, his chance to do so is 70%, and again, if he fires, the attacking unit takes a morale test.

vi. After the defender completes his actions, there is a 60% chance the pre-melee phases end. If not, it's back to the attacker. And so on...

Note that, in the above sequence, the initiative switches back and forth between defender to attacker, and after each switch, the chance that the whole procedure comes to a halt increases by 20%. Which means that, at most, there will be 5 pre-melee-phases before combat is resolved.

The above pre-melee sequence was used to good effect by the Confederates just to the west of Smallsville. I had taken one of my Union brigades (3 regiments headed by General Thwackett) and plunked it just to the south of Smallsville, trading fire and '-eeping the Rebels in the town occupied.

Then, to the west of the town, I sent my second 3-regiment brigade, commanded by General Prippett, straight north, attempting to outflank the townies, eventually to come in on them from the west, simultaneous with a frontal attack from my first brigade.

Alas! It was the Confederate cavalry to the rescue! As Prippett's brigade marched north, the Southern cavalry descended on them, catching them in column-of-march formation, which, in the Simon scheme of things, produces horrible consequences to your melee dice.

The first Confederate cavalry regiment contacted my leading regiment, and in the first pre-melee phase, I diced (70%) to see if the unit could change formation, to deploy from column to line. No luck!

There was now a 20% chance the pre-melee phases were over, and sure enough, they were! My unit never got another chance to deploy. It was now "melee time", and we used the second of the two sets of procedures instituted to prevent the attacking side, i.e., the active side, from walking all over the inactive side's defending unit.

In this second procedure, we use what I term the "Combat Radius" CR) technique to select the units which engage and contribute their combat points to the melee.

The attacking side dices for the CR, which can be zero inches or 6 or 12 inches. All units within the circle defined by the CR can add their points in the fight. If a zero radius occurs, then only the 2 units in contact will engage; if a 12 inch radius turns up, then a huge number of units may suddenly find themselves scooped into the melee.

Since the determination of the number of units engaged is essentially taken out of the hands of the attacking side, this, in effect, prevents the active player from ganging up on one particular unit.

In our battle, when Southern General Tony Figlia, in command of the Confederate cavalry, diced for his CR, it turned out to be a full 12 inches, which permitted him to include the points of both of his cavalry regiments.

In contrast, even though the CR included my entire brigade, I couldn't add any combat points in, since all of Prippett's units were in column-of-march, and only deployed units can participate in combat.

Naturally enough, it was no contest, and Prippett's first regiment fled.

On his bonus move, a breakthrough move, the Figlia cavalry contingent made contact with Prippett's second regiment, still in column, and... WHAMNIO!... another regiment sent running. This regiment, too, failed to deploy during the pre-melee phases.

The result of the cavalry charge was that my flank march to the west of Smallsville with Prippett's brigade was stopped, and Smallsville was no longer threatened by the Union forces.

On the eastern half of the field, however, General Lambert's Union attack on the Southern-held town of Buttcrack proved a masterpiece of tactical skill.

First, during the pre-melee phases, whenever it was the Union's turn to fire, General Lambert's twinkling dice produced a marker on the defending Confederate unit. And second, when General Lambert diced for his CR, it turned out to be 12 inches, i.e., a combat zone with a 24 inch frontage, scooping in just about every unit in the center of the field, resulting in the mother of all melees.

The actual melee procedures are fairly simple, composed of four phases:

- a. First, dice for the CR, determining which units add in their combat points.

b. Each participating infantry stand contributes 4 points, and each participating cavalry stand adds 6 points.

c. After the totals for each side are computed, each 10 point increment yields a 10-sided Hit Die, and a roll of 1, 2 or 3 on a Hit Die places a marker on the opposing force.

d. The winner of the melee is a function of two parameters: N, the number of stands involved, and M, the number of markers on all opposing units. Each side adds N+M, and multiplies by a 10-sided die. The higher product wins the melee.

Note that in the determination of the winner, all markers on the opposing forces are counted in the final tally, which means that a unit that already has markers on it, may, if it is included in the area defined by the Combat Radius, and if it is called upon to participate in melee, prove to be more of a detriment than a help.

General Lambert totaled his points, grabbed his allotted Hit Dice, and scored lottsa 1's, 2's and 3's on the defending Confederates, each such hit, in effect, driving a nail into their coffins.

When the tallies were completed, the number of markers on the defending Confederates far outweighed those on General Lambert's Union units, and he easily defeated the Buttcrack defenders. 'Twas no contest. Into Buttcrack marched the victorious forces of General Lambert. But now there arose a discussion concerning who had won what. The Lambert Union forces had won Buttcrack, but the Simon Union forces had failed to win Smallsville. Was this a standoff?

Missives were immediately sent to the War Departments in both Washington and Richmond... neither has yet replied.

Although the War Departments were silent, those on both sides of the table gave General Lambert a "Job well done!" We recognized a true warrior, a man of the sword, a soldier of the old school.

The "ride-to-rally" Procedure

Here, too, in this game, as in others of recent vintage, I employed the "ride-to-rally" procedure.

Three markers were permitted a unit; the fourth caused a stand to be removed. The ride-to-rally sequence permitted each side, during its rallying phase, to attempt to remove existing markers.

For this purpose, Division Officer figures were used. Each Division officer diced for the distance on the table he could move (18, 24 or 36 inches), and off he went.

When he arrived at a unit, he diced (70% chance) to see if he removed a marker; he could repeat the effort if his attempt proved successful. If not, he had to ride on.

Back to PW Review April/May 1994 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com