In the October, 1991 issue of the REVIEW, I described the initial phases of this little known, and at first unsuccessful, effort by Napoleon, as he attempted to conquer the interior of Mongolia. Perhaps he thought that, by invading from the east, he could get a hammerlock on Czarist Russia. Alas! Having been defeated, upon his return to France, the Emperor ordered that all records of the attempt be erased from the history books, and consequently, there is very little documentation on the subject.

In the October, 1991 issue of the REVIEW, I described the initial phases of this little known, and at first unsuccessful, effort by Napoleon, as he attempted to conquer the interior of Mongolia. Perhaps he thought that, by invading from the east, he could get a hammerlock on Czarist Russia. Alas! Having been defeated, upon his return to France, the Emperor ordered that all records of the attempt be erased from the history books, and consequently, there is very little documentation on the subject.

The October 1991 article focused on a strategic set of rules called POINT OF ATTACK; this current article uses a different approach to the strategic game.

The term "large scale" in the title doesn't refer to the playing field... this was still gamed on the ping-pong table... but in the sense that a single stand of 15mm Napoleonic figures represents a brigade, and two to four stands a division.

The key figure on the field is the corps commander, for he's the one who can send his divisions out, assigning each one a strategic objective. In this scenario, the key objectives were a number of border towns in a neighboring country... the goal for the French, the invaders, was to get a foothold in Mongolia, prior to mounting a full scale occupation.

No doubt eyebrows will be raised when I speak of a common border between France and Mongolia, but let me quote from the 1991 article in the REVIEW:

- ... the map shows a common border between France and Mongolia, and a common sea coast. I make no apologies for this; the map was found in 1857 amongst the possessions of a Mongolian sea trader named Zintar, and I reproduce it here for whatever historic value it might have.

The ping-pong table represented the Mongolian portion of the Franco-Mongolian border territory, with each town manned by an assortment of Mongolian troops. Initially, all French units were off-table, back in France, ready for the leap into enemy lands.

The "leaps" would be large, for each Corps Commander was given a basic percentage chance to move his troops - called the Basic Coordination Factor (BCF) - plus a number of Coordination Points (CP) which he could use to attempt to send his units off to their objectives anywhere on the field. The BCF's and CP's represent, in numerical fashion, the strategic capability of the Commander to move his troops cross-country.

Each division has to be issued its own orders. The chance, C, to successfully move a division cross-country in a strategic move is a function of 5 factors:

- C =

+ Number of Corps Commander's Coordination Points (CP) assigned to the move

+ Corps Commander's Base Coordination Factor (BCF)

- Distance of Corps Commander from division

- Distance to be moved

- 10% for each obstacle in the path of the move

Note that there's no limit to the fourth factor, the distance to be moved. This is a negative factor (which can be rather large) , to be balanced by the first two parameters on the list, each of which is positive, and each of which is contributed by the Commander:

- First, the Coordination Points (CP) he wishes to devote to the effort. Each Corps Commander is initially given 400 to 500 CP. He points to a division, allocates as many of his CP to its strategic move attempt as he desires, and deducts these points from his grand total.

Second, even if the Commander runs out of CP, he's got an inherent Base Coordination Factor (BCF) which, while small, at least gives him a base value on which to fall back. The BCF's assigned to each Corps Commander run from 40% to 60%.

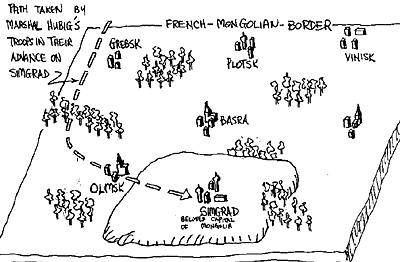

The French objective was to take the capital of Mongolia, the city of Simgrad. Marshal Fred Hubig, peerless leader of the French forces, had no direct route into Simgrad from the French baseline, thanks to the clever way (if I do say so myself) that the terrain was laid out. Entering on his baseline, he had to pass through at least one fortified city to get to the capital.

And so Marshal Hubig took the First French Corps, headed by Napoleon himself, and moved the Corps cross country and set up camp outside Olmsk, one of the few cities on the field in which no Mongolian troops were posted. The Corps commander, Napoleon, had a large supply of movement points, sufficient to permit the cross country trip to be made. f1 img

The success of Napoleon's cross country move depended upon several factors. These factors were determined by laying a straight edge from the starting point to the end point, and noting what the line intersects.

- a. Each corps commander is given a Base Movement Factor (BMF) of either 40, 50, or 60 percent, which is the chance of him completing a move for one of his divisions. Napoleon had a 60% MF.

b. From this, two items are subtracted. First, the distance he wants the division to move. Here, the unit was to travel 35 inches. Subtract the 35 from the BMF of 60, and the chance of success was reduced to 25 percent. The second factor was that the move crossed through a wooded area; each area of rough terrain that is traversed deducts another 10% from the percentage, hence the probability of success was now 15%.

c. The 15% figure can be increased, however, by using a supply of Movement Points (MP) alloted each corps commander. Here, Napoleon was given an initial total of 500 MP. He took 85 of his 500 point total, added it to the 15%, and the chance of success was raised to 100%. This left him with 415 MP for future division moves.

d. With a 100% chance of success, the division was picked up and placed at its desired destination. Note that at the beginning of the game, with each corps commander having anywhere from 400 to 500 MP, cross country moves are made quite easily, and all the troops on the field are very mobile. As the battle continues, however, and the MP are used up, the forces slow down a bit. For example, around Turn 5 or so, several of the defending Mongolian corps commanders, due to the need to race their troops around the field to plug up the gaps caused by the advancing French, had less than 100 MP left.

Now it was time for the second division in the corps to move, and the procedure was repeated. Another 85 MP were used up. Which meant that when the third division finally moved, Napoleon had some 245 MP left.

The sequence consists of a series of strategic and tactical movement phases:

- a. The active side selects one division in each of his corps, and moves them any distance desired across the field. The only limiting factors are the number of Movement Points available to each of the corps commanders, the distance to be moved, and the rough terrain traversed during the move.

b. After each corps commander moves a division, there is a 20% chance that the side's strategic movement phase is over, and the other side's begins.

c. If the side's strategic moves continue, each corps commander selects a second division. This time there's a 40% chance to end the phase. Thus each time a division is moved, the chance of the phase being terminated increases by 20%. When Napoleon moved his corps cross country, he had three divisions to move and was lucky enough to be able to move all three without the phase ending.

Finally, the French strategic movement ceased, and we Mongolian commanders moved our own troops cross-country, pouring into Omsk to hold the city. At the same time we moved to Omsk, I moved several divisions to Vinisk, a town on the border which the French had approached.

Sam Hepford headed the French corps which advanced on Vinisk, and after the Mongolian strategic phase ended, a phase combining both tactical and combat procedures began.

- a. First the attacking forces deployed. It should be noted that strategic movement can only be accomplished by units in column of march. They zip cross-country in column, and

it's only on the tactical phase that they deploy for combat.

b. Sam diced to see if each of his attacking divisions successfully deployed for combat. There is a basic 70% chance to do so. Of his three divisions on the outskirts of Vinisk, two of the three deployed; the other remained in march column formation.

c. I diced to see if my defending divisions deployed; all of them did so.

d. Both of us now set up our deployed forces in two lines, a front attacking line, and a reserve line.

e. We now each referred to our own Combat Deck of 10 cards, which were drawn alternately.

There are four types of cards in the deck:

- There are 4 "Strike" cards permitting a strike to be made at the enemy. If successful, one or more markers are put on the target units.

There are 3 "Test" card mandating that all opposing units test to see if they maintain their place in line. The markers received via the strike cards are used to modify the dice throw.

There are 2 "Reserve" cards which permit the reserve to enter the battle. The incentive to have a reserve is based on their striking power. For example, when a strike card is drawn, each infantry stand adds 20% to the chance of producing an impact on the opposition. When reserves are allowed to be committed via the appropriate card draw, each infantry stand contributes 60% chance to strike.

There is one End-of-Combat card, which signals that the battle is over and results have to be assessed.

When the combat at Vinisk began, Sam drew a strike card, and I indicated to him that each 'unit' added 20% to the total chance of his putting a marker on my troops.

What followed next seemed to indicate we came from different countries. In a sense this was true, for he was French, and I was Mongolian. For a moment or two, we weren't speaking the same language. Both of us looked at the figures on the table, and we each saw something completely different. Sam pointed to his two deployed divisions, and the following conversation took place:

- Sam: There's 20 points for my first 'unit', that 4-stand brigade, and the other

4-stand brigade in the front line contributes another 20, giving me 40% chance.

Me: No, you've got 8 'units' x 20, or 160%, to hit.

Sam: No, I only see two 'units', so I've got 40 percent.

Me: No, by each 'unit' is meant a stand, and with 8 stands, you've got 160 points.

Sam: Why didn't you simply say 'stand' instead of 'unit'?

Me: Sometimes by 'unit' I mean "unit', and other times I mean 'stand'. You've got to keep on your toes.

Sam put a couple of markers on my units via his Strike cards, and I was lucky enough to draw a Test card causing Sam's units to see if they held position. Test cards are bad business for the tester, for the result may be that stands drop out of combat, and hits are registered on the corps' data sheets.

Neither of us had the opportunity to commit our reserves. One of us finally drew an End-of-Combat card, and we looked at 2 parameters: the number of stands remaining in combat, and the hits registered on the enemy data sheets. Add these 2 values, multiply the sum by a 10-sided die, and the higher product wins.

It turned out that I held Vinisk, and drove Sam's forces off.

At Omsk, unfortunately, the reverse was true. The French Hubigians gave the defending Mongolian troops more than their share of markers, hence when a when a Test card was drawn, each brigade with markers used the table shown below.

Tossing high numbers on the chart is to be avoided, and since each marker biases the dice throw by 30 points, a Test card wreaks havoc with the front line stands. Which is what occurred at Olmsk, as the Mongolian stands were forced to withdraw.

- Dice

Throw

-------------------------------------------

- Brigade falls back Register 3 hits

- Two stands fall back Register 2 hits

- One stand falls back Register 1 hit

- No effect

By the time the End-of-Combat card appeared, there were few stands remaining in the Mongolian front line, and the defending units pulled back for a last stand at the capital of Simgrad. We Mongolians were going to do or die at Simgrad!

We died.

Simgrad had fallen, but we had one last chance to assemble our forces and retake the city. In charge of the assault was that intrepid warrior, Mongolian Field Marshal Figlia. Alas, I had forgotten that like General George Pickett, who graduated last in his class at West Point, so had Marshal Figlia graduated last in his class at Mongolian General Staff School (MGSS).

And if one keeps in mind that the standards of MGSS are slightly below that of West Point, one sees where we're going.

During the last strategic march phase, we assembled about five divisions on the outskirts of Simgrad, ready to deploy, ready to win back our beloved capital. It was a magnificent sight... row after row of yurts and yogurt stands.

Then came the deploy and combat phase, and at the beginning, I was preoccupied with defending Vinisk against yet another assault by the good General Hepford. I had siphoned off several brigades to Simgrad, and my defending forces at Vinisk couldn't withstand the Hepford onslaught. Vinisk fell, and I retreated.

Then I turned my attention to Simgrad, expecting to see an array of proud Mongolian brigades, deployed and drawn up in battle formation. To my horror, I noted that of the five divisions sent to free the city, only two had deployed!

Marshal Figlia had flubbed the majority of his 70 percent dice tosses to deploy!

Simgrad was lost forever. Napoleon had cornered the yogurt market! As a last thought, it was obvious that Marshal Figlia had to be banished. Usually, one is banished to Mongolia... this brings up the subject as to where one is banished from Mongolia... no doubt it will keep the military thinkers busy for years to come.

Back to PW Review September 1993 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com