The year: 18xx. The place: somewhere in Europe. The forces: British vs French. The rules: a superior set, a veritable source book (if I may quote Mr. Scotty Bowden of EMPIRE fame) of warfare in the Napoleonic era.

The year: 18xx. The place: somewhere in Europe. The forces: British vs French. The rules: a superior set, a veritable source book (if I may quote Mr. Scotty Bowden of EMPIRE fame) of warfare in the Napoleonic era.

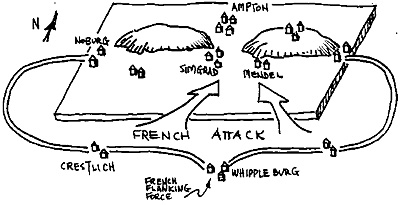

The British commander, one General F. Hubig, was permitted to place his defending forces anywhere on the field. There were seven towns, each with a victory point value, and, initially, the Hubigian units were spread from one table edge to the other, as units were placed in each town.

Opposing the British were French generals Haub and Simon, who not only had a greater number of units... since they were attacking... but also had a flanking force, located off-table, destined, they thought, for a most glorious, surprise flank attack on the Brits. Alas, 'twas not to be.

The key to the battle was the town of Ampton, worth 20 victory points. There were several '10 pointers', located toward the middle of the field, and there were two '5 pointers': one situated at the eastern end; the other, a town called Noburg, at the western end. These '5 pointers' were important to the attacking French, for it was at one of these towns that the flanking force was supposed to make its way, there to enter the field, and shout "Surprise!!"

I was in command of the flanking force, Colonel Largefellow's brigade, and chose to have it enter at Noburq. As shown on the map, the force had to travel from its initial off-table location at Whippleburg and through Crestlich, to get to Noburq.

The probability of successfully traversing each leg of the journey was 70 percent. At the end of five turns of play, the force was still at Crestlich... it simply refused to set out on its journey. Colonel Largefellow couldn't get his men into first gear. Another way of saying that was that, for the life of me, I just couldn't get a percentage dice throw below 70; out of five tosses, only one was successful.

Unfortunately for the command staff of Haub/Simon, our grand strategy was based on General Largefellow's flank march. We decided to plow straight up the middle of the field, right toward Ampton. Our thought was that concentrating all our units in the center of the field would draw the British forces to the center, hence leave a gap at both ends, in particular, at Noburg.

The strategy worked, and the Brits were, indeed, drawn to the center, but the flankers never showed up, thus nullifying a good day's work.

In anticipation of Largefellow's surprise attack, I formed every unit in my entire division, two brigades worth, some nine battalions, into assault column.

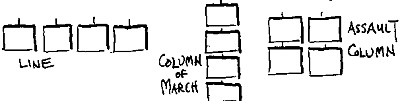

Under the rules system, there are 3 basic infantry formations:

Under the rules system, there are 3 basic infantry formations:

In line, all stands fire; each adds 20% to the chance of hitting the target, hence the 4-stand battalion has a basic 80% hit probability.

Column of march is not a combat formation, hence no firing is permitted.

Assault column has the first rank of 2 stands firing... at 20% each, the probability of hit is 40%. Assault column also adds points in melee because of the supporting second rank. Thus the fire power is degraded, but the melee value goes up.

And so when I formed up with each unit in assault column, I sacrificed fire power for 'combat power', thinking that with the soon-to-come support of Colonel Larqefellow's troops, I didn't need to fire.

Up the field... or, perhaps, down the field... marched my stoic, grim-faced men, bayonets fixed, ready to draw British blood. Their first stop: the town of Simgrad, held by a battalion of dreaded Highlanders, the 1/42.

Leading the way for my boys was the 7th Battalion, the men of the 7th even more grim-faced than those in the following battalions. Perhaps they sensed what was about to befall them.

During the regular movement phases, infantry move 8 inches, but they cannot approach an enemy unit closer than 2 inches. Only during the combat phase do opposing units actually close to contact.

Digression

The fire phase is sandwiched in between movement and combat. The minimum 2-inch distance between enemy units during movement ensures that all units are viable targets during the subsequent fire phase; units are not yet defined to be "in melee" and hence can be fired at by any weapons able to bear.

I first noted this approach in Barry Gray's KOENIGKRIEG rules, and have made considerable use of it.

To my mind, this presents a cleaner configuration than is given in some rules sets wherein units, during movement, actually march into contact with the opposition. Here, the opposing, touching units are immediately defined to be "in melee", and in the following fire phase, cannot be fired at except by each other. And sometimes, not even by each other.

which means that two engaged units can sit in midfield while firing goes on all about them, yet they remain immune from any of the fire effects. This restriction during the firing procedures never sat well with me. End of digression.

Back to the Game

And so, on my movement phase, the Fighting 7th approached Simgrad, drawing to the requisite 2-inch distance, ready to charge forward when the combat phase commenced.

But first, the fire phase. The 7th took it on the chin, as the defenders of Simgrad and their nearby support units poured it on. The 4-stand defenders, at 20% per stand, each had an 80% chance to impact, and impact, they did. In reply, the 7th, and its own supports, in their assault column formation, fired back with a paltry 30% probability-of-hit, and, unsurprisingly, missed.

The 30% figure arose from:

2 stands firing x (20% per stand - 5% for target in cover) The last procedure of the fire phase is to have all units which received hits take a morale test. Despite the plethora (in fact, several plethoras) of hits on the 7th's data sheet, the unit passed, and it was now melee time.

Situated 2 inches from Simgrad, there was one last difficulty to overcome before the 7th could make contact. It was assumed that the defenders in the town had piled up all sorts of rubble and other obstacles in the path of the oncoming forces.

This barrier was defined as rough terrain, and to actually enter the town and engage, the 7th had a 70% chance of successfully leaping nimbly and gazelle-like over the rubble to cross bayonets with the opposition.

"Ready, men! At the mark! Get set! CHARGE!" I cried, and I tossed my "rough terrain" dice. Helas! I couldn't roll under 70!... and the 7th stood there, transfixed.

This put a triple whammy on the 7th, for now it had to undergo another fire phase while it remained in the open, pass another morale test, and, of course, toss another 70 to leap over the rubble.

Again the defenders poured it on, again the 7th passed a morale test, and again I tossed the "rough terrain" dice.

And again, the 7th couldn't get over that @#%%&*! rubble! I don't know what the defenders had piled up, but it certainly proved an impassable barrier.

This time, the Fighting 7th wilted under the defenders' fire; the unit failed to pass a morale test, and fell back.

Next in line was the Fighting 11th Battalion (all my units are "Fighting" ones)... more fire, another morale test, another "rough terrain" dice throw... egad!... the Fighting 11th couldn't get into the town either!

A moment or two later, however, and the 11th won the glorious honor of being the first of my units to charge into Simgrad.

Fire Oriented Game

The rules sequence sets out a "fire oriented" game, in that weapons fire predominates over all other aspects. The sequence for a full bound consists of 6 phases:

- a. French movement (remain 2 inches from enemy units)

b. Both sides fire

c. French close to contact; resolve melees

d. British movement (remain 2 inches from enemy units)

e. Both sides fire

f. British close to contact; resolve melees

Note that there are two full fire phases per bound, during which both sides get to fire. Each fire phase employs a procedure which I ginned up rather recently. The reader will not be surprised to find out that a deck of cards is used.

There are 6 steps to be followed:

- a. Each side has its own deck of 6 cards. Each card contains a single annotation: "All units in all brigades may fire", or "Units in 3 brigades may fire", or "Units in 2 brigades may fire", etc.

b. The sides each toss dice to determine how many of their 6 cards they will contribute to a common Fire Deck. They may contribute 2, 3, or 4 cards, depending upon the dice toss.

c. The Fire Deck cards, containing the cards of both sides, are mixed randomly. One additional card is placed in this common deck, one annotated "End of Fire Phase"

d. Cards are now drawn, and the side whose card is drawn fires all designated units. Units that are hit will take a morale test.

e. The same units may fire on two or more consecutive cards.

f. Firing continues until the "End of Fire Phase" card is drawn. As indicated in the sequence listing, a combat phase follows. On occasion, the "End of fire Phase" card is the first to be drawn; in this case, we skip the fire phase completely.

Note that the above procedure over-emphasizes weapons fire much more so than the usual run of Napoleonic rules sets. One way of 'toning down' the effect is to limit artillery fire. Each battery, i.e., each gun model, dices for its ammunition supply, receiving either 8, 9, or 10 rounds for the entire battle. With lots of firing, but with a restricted ammo supply, the guns do not necessarily bang away on each fire phase.

A second way of toning down the effect is to use unit data sheets. This permits lots of hits to be recorded with a consequential gradual degradation of combat capability and morale level, instead of abrupt single stand removal, or... and I hate to bring the subject up... the use of (ugh!) casualty caps.

But Back to Simgrad

My Fighting 11th proved their worth by tossing the defenders out of the town. An attacking winning unit is permitted an 8 inch breakthrough move, but I wisely declined to move the 11th forward... north of Simgrad, the place was swarming with British units. Instead, the 11th dug itself in at Simgrad.

I had a parallel run of good luck in Simgrad's sister town, Mendel. I forget which of my units charged forward, but they, too, drove the defending force back, and entered the town.

In theory, with both Simgrad and Mendel belonging to the French, the way was open to Ampton. In practice, no, nyet, nein, non. General Hubig's British force had given us such a hard pounding, we couldn't summon up sufficient strength to push forward.

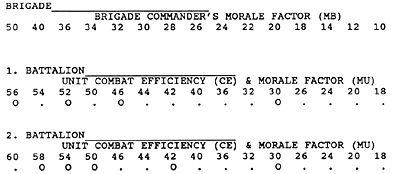

A word or two on the data sheets we used. At right is a portion of a brigade data sheet. It displays a set of numbers for the Brigade Commander, and a similar set for each of his battalions.

A word or two on the data sheets we used. At right is a portion of a brigade data sheet. It displays a set of numbers for the Brigade Commander, and a similar set for each of his battalions.

The morale level for a unit is the sum of the unit's number plus that of the Brigade Commander, Thus Battalion #1 currently has a morale level of (56: its own level) + (50: the Brigadier's level), or 106.

It would seem fairly difficult to break a unit with a 106 percentage. Three things serve, however, to reduce the level:

- a. First, the distance between the Brigadier and the unit in question is subtracted from the total. The Brigadier is in command of 2 to 6 battalions spread all over the

field, hence, on occasion, he may be as much as 20 inches from the battalion under test, thus reducing the level quite appreciably.

b. Second, as the battalion takes hits, it crosses off its own numbers, reducing its level and, consequently, the sum.

c. Third, note that the battalion data sheet contains several entries that have a "0" under them. These are "critical hits", for when this level is crossed off, so is a level on the Brigadier's sheet. Which means that not only is the morale level of the affected unit degraded, but so is the level of every unit in the brigade.

On the data sheet shown, Battalions #1 and #2 have, between them, a total of 9 critical hits, which could put a severe crimp in the Brigadier's listing.

And this is the effect from only two battalions.., with up to six on the field, the poor Brigadier can suffer from multiple wounds in short order. If all of his levels get crossed out, he retains a "residue" equal to his last recorded value, poor fellow.

The data sheet has one more use. Note that the listings for the battalions are also termed "Unit Combat Efficiency".

Im melee, when a battalion strikes, it is given a number of Hit Dice, 10-sided dice, on which a toss of 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 indicates a hit on the opposition, i.e., a level crossed out.

The number of Hit Dice is determined by multiplying the unit's level by the number of stands, usually four. Every 100 points entitles the battalion to one die.

Thus Battalion #2, with a current level of 60 (untouched), has a total number of points equal to 4 x 60, or 240... 2 dice and a 40 percent chance of a third.

Additional Hit Dice are given a unit, depending upon the situation. For example, the defenders of Simgrad got 2 dice for their defensive position.

A Battle Lost

In retrospect, we French lost the battle due to my complete inability to toss percentage dice and get a result below 70. I must admit there may have been other factors, such as lack of generalship, but for the present, we shall ignore them and focus on the dice-tossing effort.

First, it was the failure of the flanking force to move. They could have entered the field in two turns, two quicky tosses below 70... instead, at game's end, they were still in Crestlich, having a merry time, boasting to one another about what they'd do to the British when they finally got on the field.

And second, the failure of the Fighting 7th to assault Simgrad. In refusing to enter the town, they remained exposed, in the open, in a 'non-firing' formation... not only incurring hits themselves, but inflicting wounds upon their beloved Brigadier in the process, thus weakening the entire brigade.

Which meant that when the 7th finally fell back, its sister units, the ones in the same brigade, didn't have too much enthusiasm left to continue the attack. It took a battalion from another brigade, the Fighting 11th, to finally close.

Back to PW Review November 1993 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com