AWI: Princeton

AWI: Princeton

At the May PW meeting, Scott Holder put on a scenario (using a mix of 20mm and 25mm figures) of the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777, one of George Washington's few victories.

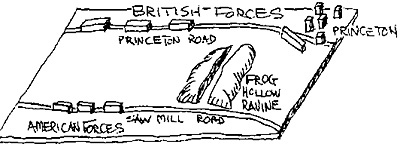

I was in command of the British 40th Regiment in Princeton... there were three other regiments, all strung out along Princeton Road. Moving parallel to our British units were a number of American units on Saw Mill Road. At the battle's beginning, neither side was aware of the other. Back in '77, it was the Brits that first spotted their opponents, giving them (the Brits) a shot at first deployment.

Scott used a variation of an absolutely stunning set of rules termed POUR LE MERITE (PLM), an award winning set (1993 Award For Historical Simulatoriness, given by the Centre For Provocative Wargaming Analysis) developed for the Seven Years War.

Scott's PLM, as did the original, focused on unit morale. Figures were not removed, but each unit was given a marker when it failed a morale test. Five or six such markers (depending upon the unit's grade), and the unit was removed from the field. Markers were "earned" due to two sources:

- a. The failure to pass a morale test.

b. When an officer was hit. Each unit had, as Scott put it, an "amorphous officer", who could add up to 2 0 percentage points to the unit's morale level. If he did so, dice were thrown, and if the toss was equal to or below the points contributed by the officer, it was deemed that he was hit, and even if the unit itself passed its morale test, the unit received a marker because of the officer's injury.

The victory conditions looked at the total number of markers accumulated by each side... when they totaled twice the number of units, there was a chance that the commander gave up the ghost. This chance increased with every subsequent marker received.

In 1777, our President, Unca George, proved himself a true hero. Unca George arrived on the scene at the time the Americans (or, more properly, the "Muricans", as they were wont to call themselves) were just about to route from the field. Curt Johnson's BATTLES OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION states:

- ... Washington realized that the panic gripping these men might spread to his entire army. Immediately, he rode between the lines, exposing himself recklessly to the fire of both sides in a desperate effort to rally the militia... Spurred by Washington's example, ...(the)... shaky line stiffened.

In our battle, however, Unca George did nothing, and unit after Murican unit failed its morale test, received a marker, and soon only we British were left on the field. Huzzah for King George! When PLM is presented for the first time to an unsuspecting audience, there's a tendency for the parties to shout: "Don't I get to toss the dice?" And at first, it is a wee bit confusing, for when your unit fires, for example, you don't toss the dice at all... the other guy does.

As an example, the morale level of a few of our British units was set at 80 percent; my 40th Regiment was at 70 percent. If a Murican unit fired at the 40th, the following would occur:

- a. First, we'd put 3 parameters of the Murican firing unit together: a range factor, the number of stands firing, and the number of volleys fired by the Muricans. The resultant number was not the probability of knocking off one of my men or one of my stands, but was used as the reduction to the 40th's morale level.

b. And so my 40th would take a morale test. From its initial morale level of 70 percent, I'd deduct whatever impact the volley had, and then, if I desired to offset some or all of the decrease, I'd use the unit officer's points to add to the morale level.

c. Then I would toss the dice, not the firing commander. If the 40th passed... fine; if it failed, it moved back and it would receive a marker.

We Brits were so enthused about our overwhelming victory against the Muricans, that we immediately accepted a challenge to do it again. Well, not exactly again... this time, instead of walking onto the field, hidden from each other, the sides simply set up along their baseline and had at it.

Which meant that we had four British units against double that on the Muricans' side. The result was that we got shot up fairly quickly. My own once-proud 40th Regiment routed back so many times I almost lost track. And each rout, of course, caused a dreaded marker to appear.

At the sixth rout, my boys had had it... off the field they ran. But then, so did the rest of the British army. Well, one out of two isn't bad.

Napoleonic: Quatre Bras

At Rich Hasenauer's house, Fred Hubig presented the Battle of Quatre Bras, using his Napoleonic era BLACK POWDER (BP) rules. In theory, this was a grand rehearsal for a game to be run at the July HISTORICON convention, catering to some 6 or 7 players per side.

BP contains an amalgam of, as I term it, the "recognizable patternry" of the Napoleonic period: it's got skirmishers and "fatigue markers" and infantry squares and "unit disorganized markers" and canister effects and markers to indicate that a unit's weapons are unloaded and British 6 pdrs vs French 9 pdrs (or is it the other way 'round?)... and so on and so forth.

It's also got a neat sequence:

- a. Each unit on the active side receives one "freebee" action (move, fire, etc.) and then, if the unit passes a morale test, it receives a second action (and elite units can attempt yet a third). This means that a unit can fire, and if it receives its second action, it can reload its weapons.

b. As the active side does all these good things, the non-active side can shout "Halt!" at any time, and attempt to get in a preemptive action, either firing or a charge to contact, thus disrupting the active side's plans in a big way. Here, too, passing a morale test will set in motion the non-active side's unit.

The Quatre Bras scenario proved to be too big a mouthful on which to chew... the table was initially loaded with 15mm troops, and since the orders of battle were to be a scientifically and historically accurate representation of those on the field in 1815, more and more troops kept pouring onto the table. In truth, to my tired old eyes, it began to look like one of the Bowden EMPIRE Napoleonic games, something definitely to be avoided.

I sat opposite Rich Hasenauer. He had the right flank of the oncoming French forces, and I had the British left flank. My mission was to hold; his was to advance.

Each of us had around a division of troops, and it took one or two turns to catch on to the sequence, after which we just sort of rolled along. We'd move and fire and preempt and melee and so on and so forth. We were having a fine battle 'twixt ourselves.

In fact, so proficient were we, that we pulled ahead of all the other encounters on the table. The other end of the field had about three million units to move and fire, a fairly time-consuming affair.

After sitting and fidgeting for some ten minutes, I shouted to Fred Hubig at the other end of the 14-foot long table: "Fred, we're going on to Turn 5, instead of waiting for you guys."

About seven minutes 'later, Rich and I completed Turn 5... the other players were still wallowing in Turn 4. This time I shouted: "Fred, we're going on to Turn 6." And we did. And we finished.

In the BP scheme of things, Turn 4 supposedly took place around 3:00 PM in the afternoon. Each turn encompassed about a half-hour, and thus when Rich and I got up to, and finished, Turn 7, and the other fellas were still on Turn 4, we were almost two full battletime hours (approximately 5:00 PM) ahead of everyone else.

Neither Rich nor I were unduly bothered by this... our flank was engaged in its own little war, and we were happy.

But suddenly... the time-space continuum was shattered! Shades of WARHEMMER! Across the field, out of another time zone, came a galloping regiment of French horse commanded by Sam Hepford.

Yah hoo! Yee hah! and BLAMMO! Right into my artillery batteries they plowed, and annihilated them. My guns, in pointing at the Hasenauer forces, were facing away from the horsemen, and presented too good a target to the Hepford cavalry.

These warriors of the past (remember they were at 3:00 PM or so, while we were functioning around 5:00 PM) didn't stop there. Another cavalry regiment smashed into one of my infantry units. The infantry, thanks to the BP provisions for a timely preemptive action before contact, passed a morale test, and were able to form square and beat back the ghostly Hepford cavalry of another time, another era.

What saved my forces was a conglomeration of several factors:

- a. As the cavalry came zipping across the table, they acquired a number of 'fatigue markers' which reduced both their morale level and their combat capability.

b. When my infantry unit successfully formed square in the face of certain disaster, and beat off the cavalry, I think that General Hepford lost heart, for he promptly withdrew the remainder of units. Indeed, I fervently hoped he'd withdraw to his own time-space continuum.

c. It was just about this time that Fred Hubig decided that there were too many troops on the field and_ that it would take another 3 or 4 man-years to come to some sort of resolution. "Let's pack it in!", he said.

And so I was spared the humiliating experience of having my infantry units wiped out by the ghostly cavalry of times past.

This third note in this article concerns a set of rules I ginned up for 15mm scale modern armor. Well, not really modern armor, but World War II armor... modern enough for me.

About four or five months ago, I happened to come across a book on game design, published in the mid 70's, and authored by Steve Jackson... of CAR WARS fame. Jackson is a successful board-game designer, and his book, while focusing on board-games, did contain some general information pertinent to the set-up of miniatures rules.

In particular, I was interested in the chapter devoted to game sequences. And, most in particular, the most interesting of all of Jackson's comments was to the effect that my favorite sequence was definitely not one of his.

He was referring to the A Move/B Fire/B Move/A Fire sequence.

For years, I had grafted this sequence onto any rules set I could lay my hands on. It made sense to me... Side A moves, and then, before his own troops can fire, he's subjected to Side B's fire. If nothing else, the procedure prevents the "gotcha" effect often found in other rules, wherein the active side's units can move up to an advantageous position and then fire before their passive opponents can react.

Maybe so, said Jackson, but as a gaming sequence it is a poor one. If a side is to be subjected to enemy fire after it moves and be ore its own units can fire, this puts a huge damper on what should be a swift-moving game. He reasoned that no one wants to move up and immediately be shot at; units will tend to take cover rather than act aggressively. A game, continued Jackson, should have a sequence wherein a side can "set the other guy up" during its turn.

Now I am a quick learner. And if a noted board-game designer says a sequence stinks... then it stinks, period. End of argument. After playing around with several possibilities, and examining the sample sequences presented by Jackson, I arrived at the current version of the sequence for my 15mm moderns game:

- Phase 1. Side A opens by firing.

Phase 2. Side A moves all its units. None can approach closer to an enemy unit than 2 inches.

Phase 3. Side B gets "opportunity fire". Not every unit on Side B may blast away, as the number of units eligible to fire are a function of the CO's capability.

Phase 4. Side A's units, within 2 inches of those of Side B's, can close assault.

Phase 5. Side A's lighter units (armored cars, light tanks, wheeled vehicles, etc.) get an additional move.

Phase 6. Side A can rally... again depending upon the CO.

You'll note, in the above sequence for the half bound, that it leads off with a fire phase for the active side, which then immediately launches into movement. This follows along the lines of Jackson's thought that, to make a game more interesting, you should employ procedures that allow you to "first soften 'em up, and then go get 'em".

An "opportunity fire" phase then follows the active side's movement, during which the non-active side gets a chance to pot the active side's oncoming units.

But opportunity fire is not the same as "free fire", as occurs on the active side's first phase. I built in a limited scope of opportunity fire, and based the volume of such fire on the commander's ability.

Each commander is rated for his Military Capability (MC), either 50, 60, or 70 percent. When the opportunity fire phase occurs, the non-active commander dices to see how many of his units can react as indicated in the following chart:

- 100------------------------------

- 50 percent of his units fire

- All of the commander's units may fire

Thus for a commander with a 60 MC, the chart becomes:

- 100------------------------------

- 50 percent of his units fire

- All of the commander's units may fire

Note that on the opportunity fire phase, all of the commander's troops may not get to fire... only if this particular commander tosses dice below his Military Capability of 60. And, on occasion, when his toss is over 60, only half his troops get to fire.

The firing procedures are based on each weapon being assigned a number of "Kill Dice", i.e., 10-sided dice, which yield the following:

- 1 Target destroyed

2,3,4,5 1 Hit

6,7,8,9,10 No effect

Note that there's 50 percent chance of producing a hit on a target for every die thrown. The accumulation of hits resulting from this percentage seems to work out for the modern era.

Back to PW Review July/August 1993 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com