I dug deep (deeply?) into the PW REVIEW files and emerged with the January 1983 issue, the first one in which an article on the "morale game" appeared.

The article centered on a set of rules for the American Revolutionary War, and the introduction explained the concept:

- Several articles in the COURIER have

stressed the "morale battle" in wargaming,

George Jeffrey's way of saying that

encounters between enemy forces are won,

not by attrition due to weaponry effect,

but by the disintegration of the opponent's

force due to a breakdown in morale. In

short, if you can scare the other guy off

the field, you've got it made.

The figures I used back in '83 were about 40mm in size, and rather klunky (apparently, being sort of klunky myself, I am drawn to klunkiness). Ages ago, Paul Koch had given me a small selection of the figures; they had been cloned in Hong Kong and appeared to be copies of the product line of some long deceased and unidentified manufacturer. Not to be outdone by the Hong Kong entrepreneurs, I immediately commenced producing my own klunky clones, gravity casting quite a number of them.

My products were now third generation clones, and if one studies the genealogical attributes of the Clone family tree, one notes that as one gets further down the line from the original family members, detail is lost, and klunkiness is increased. I'm not sure that's an even tradeoff, but ya gotta take what ya can get. If you do take the trouble to examine the figures, the most striking thing about them is that they have no faces... no mouths, no noses, no eyes. They're sort of blobby-people, but I love 'em nontheless.

The 1983 morale game took off in several directions, one of them resulting in POUR LE MERITE, circa 1986, a set of rules for the Seven Years War which I've described in several articles, the most recent being the January issue of this year.

In this latest morale game, single-mounted figures were used, and unit sizes were as follows:

- British Regulars 8 men per company

American Regulars 6 men per company

American Militia 5 men per company

Tories 5 men per company

The reason for the difference in size of the various units was that the number of figures in the company determined the morale grade, which I term the Reaction Level::

- Reaction Level (RL) = 50 + 5 x (No of men in

company)

This gives the British Regulars an initial RL of 90%, the American Regulars 80%, and so on. As men are lost, the percentage decreases.

The heart of the game is in the Reaction Table, shown below:

- 100 ---------------------------------------

Fall back 12 inches, form column. Lose 1 man.

RL ----------------------------------------

Hold position; lose 1 man if dice are even. If deployed, may advance 6 inches.

1/2 RL ------------------------------------

Hold position. If deployed, may fire.

0 -------------------------------------------

As an example, a company of British Regulars, with an initial Reaction Level, RL, of 90 percent, might, after being fired upon, have their RL temporarily reduced to 78.

Looking at the chart, they would pass successfully with a dice throw of 39 or less, might lose a man with a throw between 40 and 78, and would definitely lose someone with a toss of 79 or higher.

It should be noted in the table, that if the dice toss is low, the unit reacts favorably and is allowed a "free" shot back at the original firing unit. on occasion, this sets up an interesting firefight which continues until one of the units tosses high.

From the table, it can be noted that quite a bit of the time, when a company undergoes a reaction test, it "loses 1 man" ... one figure is placed off-table in limbo. The fellow is not entirely out of the battle, however, for he can be rallied. Remember that this is a "morale game", and no one ever gets killed in the procedures.

Even though the basic theory is that nobody dies in a morale game, bad things can and do happen, if for no other reason than to bring the battle to a conclusion.

For example: each side is given a limited number of challenges with which it can eliminate enemy companies. With 2 or 3 companies per battalion, a challenge is based on the number of temporary battalion casualties, men that have been temporarily placed in limbo for rallying purposes.

In the first cut at the rulest if one saw that a battalion has suffered heavily, and that a number of men were missing from the ranks, the chance, P, that a single company will disintegrate was:

- P - 5 x (Number of men missing from battalion)

The objective, therefore, is to pick on a battalion before its constituent companies can be rallied. If the challenge is successful, the owning player gets to select the unfortunate company that will be removed.

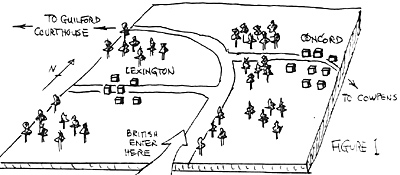

The set-up for the first game is shown in Figure 1. The British contingent came on via the central road on the southern baseline. The British objective was to search both towns, Lexington and Concord, for rebel supplies.

The American force, the Regulars, entered on the northern baseline, while the militia were given special dispensation. Those daring American Minutemen were permitted, under Rule 367, to pop up anywhere in any woods on the field to give what for to the Brits.

Battle

Battle

Fred Haub and I ran the British, Fred Hubig ran the Muricans. Muricans are just like Americans, but slightly more primitive.

On the British left flank, I took command of two detachments. First there were four companies of Tories, troops loyal to the crown, with each company consisting of 5 men. Second, a 2-company battalion of British Regulars, each 8-men strong. One would think that such a force would be more than adequate to deal with a lot of backwoodsmany Muricans... poor, primitive Muricans, who couldn't even speak British.

As my boys approached Lexington, the Muricans, already in the town, opened fire. Each man in the firing unit deducted "something" from the target unit's basic Reaction Level (RL) .

The "something" depended upon range, and was a function of what I term the Range Factor, which is the ten's digit of the range measurement. The firing procedure ran as follows:

- a.The Muricans opened up at 18 inches. The ten's digit

of 18 is 1, therefore the Range Factor is 1.

b. Each man firing will deduct an amount equal to:

- 3 - Range Factor

c.Here, the deduction per man was 3 - 1, or 2 points per man firing.

d.With 5 Muricans firing, the total deduction was 5 x 2, or 10 points off my unit's RL.

e.The initial RL of the 5-man Tory company f ired on was 75, which, modified by the -10, became 65.

f.Given an RL of 65, my targeted Tory unit now used the Reaction Table shown on the second page of this article, to see if it held position, fired back, or whatever.

Step b, above, is the critical one. At point blank range, less than 10 inches, the Range Factor is zero, and each man firing deducts 3 from the target's RL. In the teens, when the Range Factor is 1, each man deducts 2, and in the twenties, each man deducts 1.

As I remember, the first Tory unit successfully passed and held its ground. Other Murican units opened up, however, and the Tory company finally failed, retreated and lost a man. An RL check is required every time a unit is f ired upon, and it took 3 or 4 volleys to send my loyal troopers back.

Lexington and the surrounding area crawled with Muricans. In the town, in the open, and in the woods. Especially in the woods, for those Murican militia seemed to pop up everywhere, using their uncanny woodsmanlike ability - in conjunction with Rule 367 - to set up ambush after ambush.

On occasion, when fired at, my units would, during their subsequent Reaction Level tests, throw low and according to the Reaction Table, be permitted to return fire. We interpreted the "if deployed, may fire" instruction on the table to mean that a low reaction dice toss allowed the men in a company to turn and face the unit that had just fired on them. In my case, this helped quite a bit, for my troops were virtually surrounded by the rebels.

On the British right flank, General Haub took all our cavalry, 3 full squadrons, and a battalion of 3 companies - the total of which amounted to about half our force - and went to search Concord. He found no Muricans, but he did locate one of the rebels, hidden cannon, which he used as justification for keeping his men well out of the main battle near Lexington, where my valiant troopers were getting their RL handed to them.

If a company took losses and lost a man or so, it was permitted to rally by remaining stationary for a turn. Dice were thrown and the number of men that would rally back to the colors was:

- 01 to 33: No men will rally

34 to 66: 2 men will rally

67 to 100: 3 men will rally

The above rallying table is rather liberal, and so it was important to pounce on a battalion as soon as it incurred casualties to institute one of the challenges given to each side, the challenges that could result in eliminating a company. If one waited too long, the company would rally and an opportunity be lost.

At the outset, the rebels, nominally on the defensive, were given 14 challenges. The attacking British were given 18. The number of challenges was derived from the initial number of companies assigned each force. This may appear to be a lot of challenges, but in point of fact, the probabilities associated with them were low... with 4 men missing from a battalion, for example, the probability of eliminating a company would be 5, x 4, or 20 percent.

Second Engagement

For a second engagement, I actually went to the history

books and set up an historical battle, that of Germantown,

1777, in which our own George Washington got zonked by Howe. I

turned to a little known publication from Argus Books Limited,

a 1977 book authored by Don Featherstone, called WARGAMER'S

HANDBOOK OF THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE.

Second Engagement

For a second engagement, I actually went to the history

books and set up an historical battle, that of Germantown,

1777, in which our own George Washington got zonked by Howe. I

turned to a little known publication from Argus Books Limited,

a 1977 book authored by Don Featherstone, called WARGAMER'S

HANDBOOK OF THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE.

I'm afraid this was not one of Don's best efforts. Ten battles are covered, and for each the book presents a map, and a sketchy narration of what went on, and some rules in the back, and that's about all.

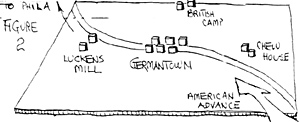

For a wee bit more information, I turned to Carrington's BATTLES OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION, which first appeared in 1877. Carrington's map was impossible to make out ' and he doesn't give a listing of the units either, but between the two books, a scenario was set up, the map of which is shown in Figure 2.

Aside from the fact that Washington lost in 1777, which seemed to be rather standard back then, the other interesting thing about the battle was that it was fought in conditions of poor visibility, so much so that one Murican unit fired on another, causing a great panic and all the other Muricans to run away.

I overexaggerate... what I said was not strictly true, not everyone ran away, since Washington did manage to retreat in good order, but retreats were his forte, so to speak.

A certain General Stephen was the cause of the Muricans firing on one another-.. without orders, he took his division, took off on his own, and bumped his troops against those of General Wayne. Wayne's men couldn't see anything in the fog, and, as the bumpees, just fired away at the bumpers. Carrington notes in his history:

- The conduct of General Stephen was

submitted to a military court and he was

dismissed on the charge of intoxication.

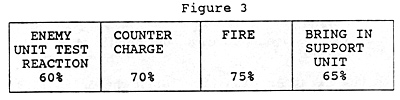

In this version of the morale game, in which the sequence employed alternate movement, I gave the non-phasing side several cards from a Reaction Deck, somewhat similar to that used in Fred Hubig's rules BLACK POWDER.

Each card listed four options, and each option was assigned

a percentage chance of success, should it be chosen. A typical

card would look like that in Figure 3:

Each card listed four options, and each option was assigned

a percentage chance of success, should it be chosen. A typical

card would look like that in Figure 3:

In most of my current rules sets which use alternate movement systems, I try to give the non-phasing side some sort of reactive action to what the phasing player is doing. In theory, of course, during the time period encompassed by a single bound, all action on the field is simultaneous, i.e., whatever goes on during both halves of the turn is "really" supposed to be happening at the same time, and it's only for convenience's sake that we let Side A do things first, and Side B do things second.

Despite this, I always feel uncomfortable when the non- phasing side just stands there, hands in pockets, and has to accept everything the active player hands him, with no chance to counter.

And so, in my mind, some sort of limited reaction is called for. I say 'limited' because, after all, it is the active player's halfbound and we can't deprive him of his just deserts. But we can put some sort of a check on his actions, and in the rules described in this article, this, in effect, is what the Reaction Deck is supposed to so.

In the game, the Muricans, ably commanded by General Dewitt, came on from the northwest corner of the field. He had three Regular battalions, a total of 6 companies, and one battalion of militia, consisting of 2 companies of 5-men each.

Of the 6 defending British companies, one was set out in Germantown, and one was placed in Luckens Mill. The rest were back in camp, waiting to be roused by the sound of musket fire.

The Muricans advanced upon Germantown, came within musket range (which had, after the first battle, been limited to 20 inches) and opened fire. Each unit, during its active phase, receives two actions, and the lead Murican cornpar,>/ deployed into line for its first action, and fired for its second.

Almost.

Defending British General Fred Hubig looked at his Reaction Card, and noted that, under "Fire", there was a 70 percent chance of getting in a preemptive volley before the Muricans could level muskets.

British dice were thrown, and Hubig was successful... his men fired first. But even before his fire was resolved, a tick mark was placed on his Reaction Card under "Fire". This mark deducted 10 percent from his reaction percentage when the next British unit chose to fire, i.e., a second British ccmj>anX- only had 60 percent chance of firing preemptively. And then a third would be reduced to 50 percent, and so on.

Back to the first British fire. When the Brits fired, the only dice tossed were__ those of the targeted Murican M zh The firing unit itself does not throw dice.

The Murican unit tested its reaction:

- a.It was a 6-man unit and had an initial level of 50

to which was added 5 percent for every man present,

or 50 + (5 x 6-men) 80%

b.Deducted from this 80 percent level was the Ifire effect produced by the Brits, which was 2 percent per man firing. Again, if you'll note, we had changed the rules from the first encounter, and tossed out the concept of the range factor, since it resulted in too many calculations. Four Brits in range now fired, and so: 80 - (2 x 4 men firing) = 72%

c. The Murican dice toss was very low, less than half the 72% level, and according to the Reaction Chart, the Muricans were permitted a free answering volley. This time, it was the Brits that took a check and threw dice. With an 8-man battalion, their initial level was 50 + (5 x 8-men) 90

d. Subtracted from this level was the fire effect produced by the Murican unit of 6 men: 90 - (2 x 6 men firing) 78,%

e. The Brits threw the dice and came up with a 67. According to the chart, they held position and didn't return fire. The preemptive action/reaction ended.

The reason I laid out all the above is that it took place even before the lead Murican company set out to do what it originally wanted to do... fire!

The British preemptive volley had set in motion a reactive sequence in which the units briefly traded fire and then stopped. Either participating unit could have failed a test and fallen back. Neither did. And so, now the Murican company fired away, the British unit tested its reaction and the game went on.

Back in 1777, the hero of the day was a Colonel Musgrave who, upon noting the advance of Washington's troops, took his men and occupied Chew House, delaying quite a number of advancing American units. In our table-top battle, I'm afraid that Colonel Musgrave's counterpart fell far short of his historical namesake.

Our Colonel Musgrave did take his men and run out toward Chew House, but just about every time his men were called upon to test their reaction, they threw high dice, fell back 12 inches and lost one man.

Note on the Reaction Card I depicted, that one of the options starts out at a 60 percent chance to select an enemy unit and force a reaction check. The Muricans took great delight at picking away at Musgrave with this option.

At one time during the engagement, about half his total force of 2 companies (16 men) were out of the battle, in limbo, waiting to be rallied.

The rally function was an option of the phasing player... instead of moving a unit, he could choose to hold it immobile for the turn, toss dice, and see if a couple of men would rally back.

Unfortunately for Musgrave, his rally dice were as bad as his reaction dice. Men kept deserting his units, and few decided to rally.

Seeing that Musgrave's units were so weakened, the Muricans decided to use yet another weapon in their list of assets. This concerned their ability to issue a direct challenge to a particular company, which if failed, would remove the company from the battle.

The Muricans had 10 companies, thus had 10 challenges. The British had 6 companies, thus had 6 challenges. The calculation, again changed from the first battle, gave a chance, P, that the target company would leave the field:

- P = (10 x men missing in target company)

+ (5 x men missing in rest of

battalion)

Musgrave's 1st Company had 5 men missing, while his 2nd Company had lost 2 men. The calculations were:

- P = (10 x 5 men missing in lst Company)

+ (5 x 2 men missing in rest of battalion)

P = 50 + 10, or 60 percent chance that the 1st Company would be removed from the battle.

A good dice toss by the Muricans, and off went the 1st Company. The 2nd Company followed soon thereafter. Poor Musgrave would win no honors today.

Things were going from bad to worse for the British as they failed reaction test after reaction test and continued to fall back in Germantown. When the Muricans had occupied about half of Germantown, I decided to cross up the Murican advance by recreating the episode in which General Stephen's troops were fired upon by friendly forces.

Fred Haub had joined our battle, commanding Stephen's forces. He moved Stephen's troops just behind another unit, and I declared that this other unit, slightly nervous because of the poor visibility, would do an about face and fire at Haub's unit.

In the Featherstone book, Don goes even further because of the visibility factor. He suggests that throughout the battle, a "local" rule be in effect that when any two units on the same side come within range of each other, a 6-sided die is tossed and a throw of I'll' indicates that the units will fire on each other.

I didn't want to go as far as Don suggested, and I settled for just one surprise volley. As I reversed the unit in front of Fred Haub's troops and shouted "Fire! 11, all I got was a small shrug of he shoulders from Fred. Big deal!

The nervous unit fired, Fred's unit took a reaction test, passed, and that was that. So much for the big surprise.

The Muricans won handily. Lots of really bad dice throwing for the British, lots of units falling back, lots of men in limbo waiting to be rallied, lots of failures at rally attempts.

But my primary focus was the Reaction Card ploy. It did just what I wanted it to do... provide a limited reaction capability for the non-phasing player.

There are only 4 reactions listed to start with, and each of these 4 commences with a percentage chance of success, so that even though a particular reaction is selected, there is always the possibility that it never comes off.

And if success is achieved, then the probability of success, the next time the option is exercised, is reduced by 10 percent.

Each turn, a single Reaction Card is handed to the non- phasing player, and as he selects option after option, he works his way down the ever decreasing percentages during the turn. The Reaction Card is then taken from him when he becomes the phasing player, and renewed again as he becomes the non-phasing player in the other half of the turn. A deck of some 16 cards presents a number of variations of the percentage chance of success of each option.

In Fred Hubig's Napoleonic BLACK POWDER, Fred hands out a number of Reaction Cards to each division of three or four brigades. The scale of the game is quite different from the American Revolution battle described above. A single card for an entire side would prove unworkable because of the sheer number of units.

In the small scale ARW battle, however, one card seems to prove sufficient.

And last, I guess should mention the melee procedures. Each man in combat is given a value, from around 7 to 15 points. Add up the points, divide by 10, and the resultant is the number of poker chips you get. Now the betting begins.

There are three rounds, and to be victorious, one must win 2 out Of the 3 rounds. Each chip wagered in each round adds 10 points to A percentage dice throw. After each round, the chips that are bet are discarded.

Can you think of a better way to fight an ARW battle?

Back to PW Review March 1992 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com