The title comes from scenario Number 1 in Charles S. Grant's book

SCENARIOS FOR WARGAMERS, published about a decade ago, and to which

our group occasionally refers when looking for an idea for a

scenario.

The title comes from scenario Number 1 in Charles S. Grant's book

SCENARIOS FOR WARGAMERS, published about a decade ago, and to which

our group occasionally refers when looking for an idea for a

scenario.

'Positional Defence' is the name of the very first scenario in the book; a total of 52 scenarios are included and, in theory, this means you could keep quite busy for a year or so. In practice, however, many of the set-ups appear uninteresting... I say this because many times we've thumbed through the book and found nothing worthwhile.

'Positional Defence' presents a Fountnoy-type of set-up, in which one force, smaller than the opposition, ensconced in several redoubts in a firm defensive line, must be attacked by a larger force.

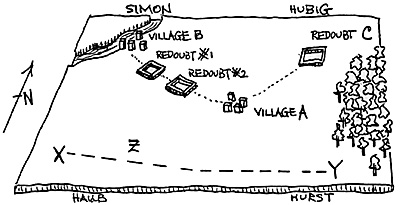

The map shows the terrain. The attacking force starts from line X- Y. The defenders occupy the line stretching from Village B to Village A to Redoubt C.

The victory conditions state that the defender must occupy two of the three key points (A,B,C) at the battle's end. And when is the battle's end?

As in most of the Grant scenarios, the text states: "The game lasts the length of a wargame day." Which sort of leaves you hanging. How long is YOUR wargame day? Mine varies... I have to milk the cows, plow the north forty, harvest the corn crop, feed the chickens...

But to the rescue came our award winning* (* Awarded, unsurprisingly, by the Centre For --Provocative Wargaming Analysis) rules POUR LE MERITE (PLM), an excellent set of Seven Years War rules (which first appeared in 1986) which defines its own victory conditions.

A PLM game is a "morale game"... when a unit is hit in the fire or melee procedures, unit casualties are evidenced by morale failures; five failures and the unit is removed from the field.

If the number of units on one side (battalions of infantry, squadrons of cavalry) is def ined as "U", a PLM battle is over when one side's units fail their morale tests a total of "U" times.

In our 'Positional Defence' battle, the attacking side had 22 units, the defending side had 14... and thus the victory conditions were clearly set out.

As an attacking commander, Fred Haub set up a grand battery - at least it looked grand to me - at point Z on the f ield, and proceeded to pound away at my Redoubts 1 and 2, prior to his advance. He also brought up a regiment to keep the troops in Village B occupied and traded fire with my defenders.

In PLM, a regiment is composed of two battalions, each of 6 stands. When a battalion fires, the following factors are multiplied together to give an impact on the target:

- NThe number of volleys fired by the battalion that turn.

This will be either 1 or 2.

S The number of stands firing. This can range from 1 to 6.

R A range factor which decreases at longer ranges.

About the only item requiring an explanation is R. Getting R is a two-step procedure. What one does first is to measure the range to the target, and look at the ten's digit, T, of the measurement. Thus if the range is 24 inches, then T is 2; if the range is 16 inches, T is 1; if the range is 8 inches, T is equal to zero.

The second and final step is to subtract T from 3. For 22 inches, 3 minus 2 is 1, and this is the multiplier R. Similarly, for 5 inches, T is zero and 3 minus zero gives an R of 3.

Note that if the range is 43 inches, T is 4, and 3 minus 4 gives a minus 1 (-1) for R. This is definitely a no-no; one can't have a negative multiplier for the firing procedure. Which means that if T is 3 or larger (ranges in the 3 0 1 s or greater) , the musket effect is nulled, giving the musket a maximum range of 29.99999 inches.

With the above as background, I opened fire at Fred's advancing troops at 14 inches, giving a T of 1, and 3 minus 1 gave my battalion an R of 2.

The battalion fired twice (N = 2), and all 6 stands fired (S = 6), and when all these good things were multiplied together, one had:

- P = N x S x R = 2 x 6 x 2 or a product, P, of 24.

What to Do?

Now the question arises: what does one do with the product P of 24?

The answer: one simply subtracts this from the target's morale level of 80 percent. The result is 80 - 24, or 56 percent, the level at which the target will test morale.

Note that the product P represents the impact of a volley on the target unit. The greater the value of P, the more severe the reduction in target morale level.

Fred's battalion took a test at a 56 percent level and failed. It fell back 12 inches, and received a marker indicating one morale failure had occurred.

At the end of our half of the turn, I noted that four attacking units had failed morale tests and received markers; four markers of the total of 22 we needed to inflict on the advancing troops to convince them to go home.

Now it was the attacker's half of the first turn, and on they came, accompanied by the fire of several cannon. In the PLM sequence, a card is drawn for the active side, indicating the number of actions available for that side. The cards are annotated "2", "3", and "4" , and if, for example, a "4" is drawn, several combinations are possible:

- A battalion may hold position and fire. The four-action

sequence is Fire/ Load/ Fire/ Load, hence the unit volleys

twice.

A battalion may move 3 inches per action. It could move a total of 12 inches for all 4 actions.

A battalion could move for two actions (6 inches) and then Fire/Load, i.e., fire once.

At the end of the first turn, it turned out that we defenders also had four markers. And at the end of the second turn, we were again tied with the attackers at about 8 apiece. If the rate of attrition held even, then, by definition, we lose, since we only had to reach 14 markers in contrast to the opposition's 22. What to do??

About the only thing that Fred Hubig and I, as the defending commanders, could think of was to call the opposition names. This really didn't work... but fortunately, what did work was to roll lots of low dice on our units' morale tests.

The basic morale level of most units was 80 percent (elite troops are 90), and this was modified by two factors: first, was a deduction for the impact produced by the enemy, and second, was an increase provided by the Regimental officer... an augmentation of up to 20 percentage points.

The Regimental Officer could do this only so many times, however, for each time he assisted one or his units, he was at risk

His percentage risk factor was the number of points with which he assisted his unit... and sooner or later, the statistics will prove out and he'll be carried from the field, mortally wounded.

Bob Hurst commanded the attacking force's right flank troops on the eastern side of the table. He launched his heavy cavalry in an attempt to power through our lines between Village A and Redoubt C.

The heavy cavalry made contact with one of Fred Hubig's defending Grenadier battalions, and in the ensuing melee, the impact on the opposing units was resolved in 2 phases. First, the determination of casualties (morale markers), and second, the determination of which unit held position.

For the Cavalry

- A basic morale level of 80 percent, modified by

the effect of the Grenadiers.

Each Grenadier stand (6 in the battalion) reduced the cavalry's morale level by 2 (-12 total).

The heavy cavalry unit had a sister unit in a supporting role, hence added 10 percent.

Add up the above, and the resultant morale level for the cavalry is 80 - 12 + 10, or 78 percent.

Unfortunately, the cavalry failed to toss below the required 78 percent. They received 2 markers.

For the Elite Grenadiers

- A basic morale level of 90 percent, modified by

the effect of the cavalry.

Each heavy cavalry stand (4 in the squadron) reduced the infantry's morale level by 10 points.

The total for the battalion of Grenadiers was, therefore, 90 - 40, or 50 percent.

Fred's Grenadier throw was magnificently low, well below half of the resultant morale level. The Grenadiers received no markers.

Thus ended the casualty assessment phase. For the second phase, the determination was made of which side held position.

The cavalry had received 2 markers, each marker knocking 10 points off the basic morale level of 80, giving a resultant of 60 percent. Unfortunately, the cavalry failed this throw, not tossing under 60, an back they went.

The Grenadiers had received no markers; their morale level remained an untarnished 90 percent... they made their 90 percent throw, and held their position.

Keep in mind that in any of the above morale calculations, the Regimental Officer could be tossed into the equation adding yet another 20 percent to his unit's morale level.

Note that in the above descriptions of both the fire and melee procedures, the one, the only, the sole, parameter of interest is the unit morale level. When you fire, you decrease the target's morale level, and when you charge forward to contact the opposition, you decrease his morale level. This is the reason I term PLM as a "morale game" ... nobody dies... nobody gets hurt... casualties are never removed... a unit hangs in there until, burdened by the fact that it has failed its morale test 5 times, it simply disintegrates, flees the field, is picked up and is removed from the table.

The other item of interest concerning PLM is that when a unit does fail a morale test, it doesn't route in a disgraceful manner. Rather does it fall back (12 inches), gracefully, in order, maintaining formation, merely seeking a brief respite from the fray before being placed in the front line again.

Supposedly, this reflects the professionalism of the units of the Seven Years War era...

In our battle, I must admit that Fred Hubig and I did good work; we managed to inflict more markers on the attacking units than they inflicted on us, enough so that we both arrived at our critical numbers of 22 and 14, respectively.

I should note, by the way, that for markers, we employ a number of single mounted standard bearers. Each time a unit fails to pass a morale test and steps back gracefully, we plunk a bold looking standard bearer next to the unit. Which means that those units that march around with lots of pennants and flags boldly flying, are the units that have proven the most cowardly...the more morale failures, the more flags.

At Village A on the western end of the field, I managed to knock off the Regimental Officer of one of Fred Haub's advancing regiments. Fred had used the officer to augment the morale level of one of his battalions by 20 percent. The battalion passed its test, but the Officer was now at risk for the number of points he contributed, i.e., 20 percent.

I tossed the dice and threw under the requisite 20, thus removing the officer. There are procedures for replacing officers that die in battle, and before they could be implemented, I thought I'd take advantage of Fred's regiment which was temporarily leaderless.

In each of their morale tests, whether from fire or melee, until a new Regimental Officer appeared, the battalions in the regiment would suffer a 20 percent decrement in their morale level.

And so my troops in Village A poured out of the town, contacting Fred's oncoming troops. From the Sequence Deck, I had drawn a 01311 action card for our side. The permitted three actions allowed my battalions to (a) fire once, and (b) move twice.

And so, for the first action, my lead unit fired, decreasing the target battalion's morale level, but the unit's resultant dice throw for its required morale test was low enough to pass.

Then, for the remaining 2 actions, my battalions advanced at 3 inches per action, 6 inches total, into contact with Fred's units.

It was during this melee that both sides reached their critical points... 22 markers for the attackers and 14 for us.

Our side tested first. The victory conditions state that when the critical number of markers appears, there is 60 percent chance that the Commanding Officer tosses in the towel, and orders his units to retreat.

But there is one saving factor. The Commanding officer is given 50 points which he may use to decrease the 60 percent chance of defeat. He doesn't have to use the 50 points up at one time... he can use, say 35 points now, leaving 15 in the kitty, and the 35 will decrease the chance that he is defeated to 60 - 35, or 25 percent.

The reason he needs to keep some spare points in the kitty is that even if he passes now, the very next marker his side receives will trigger yet another test, this one increased from 60 to 70 percent. Each successive marker increases his "defeat percentage" by 10 percent.

For our test, a quick conference 'twixt Generals Hubig and Simon resulted in our tossing in the entire 50 points at one fell swoop. We were not so concerned with the future as with the "now" ... we felt that if we could pass this first test, the opposition would fail theirs.

And so our 50 point allotment decreased our "defeat percentage" to 60 - 50, or 10 percent chance of losing the battle.

Helas! I could not throw above the 10 level... I tossed a 01511 to the hoots and jeers of the opposition. And, I noted, difficult though it was for me to believe, some of the hoots and jeers seemed to emanate from my side of the table as Fred Hubig, my fellow commander, looked rather cross-eyed at me.

The opposition, of course, easily passed their "defeat" test...end of battle, end of game.

Back to PW Review January 1992 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com