Wargames using combat zones, i.e., different regions as you approach the enemy, have been around for some time. The WR6 siege rules employ zones, and several rules sets define two basic zones: one for "strategic" moves, one for "tactical" moves.

Fred Haub, about 10 years ago, played with zones; his thought was that as your troops came closer to enemy lines, it should be more and more difficult to urge them on. The closer you were to the opposition, the lower the dice throws required to keep your men going.

Recently, LEGACY OF GLORY (LOG) appeared, using zones, an effort which greatly impressed me, and I thought I'd try my own hand at zone systems.

As soon as I presented the results on my ping-pong table, Fred Hubig commented: "Aha! Looks like LEGACY OF GLORY to me!"

Not so, was my response. I have a "Hostile Zone"; does LEGACY OF GLORY have a "Hostile Zone"? Certainly not!

LEGACY OF GLORY uses an "Engaged Zone"; do I use an "Engaged Zone"') Certainly not!

I use a "Free Zone"; does LEGACY OF GLORY use a "Free Zone"') Certainly not!

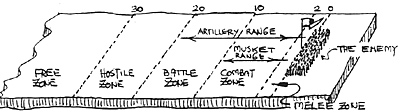

And so, having adequately disposed of the accusations of plagiarism, I continued to explain the Simon system. Below is Figure 1 which diagrams the 5 zones defined in the game. Note that the width of all zones, with the exception of the very last one, the Melee Zone, or close-to-contact zone, is 10 inches.

The zone furthest from the enemy, the Free Zone, is just that. Movement distances are large (40 inches for cavalry, etc.) , and troops can fairly well flow back and forth along the table from one area to another. This zone, in which your forces are 30 inches or more from the enemy, is the one in which reserves can be transported to the various sectors of the battlefield.

The next zone, 10 inches in width, extending from 30 down to 20~ inches from the enemy, is the Hostile Zone. Units are just outside of artillery range here, and this is the zone in which units should form up for battle.

I should mention that once you hit the Hostile Zone, movement from that point on is from zone to zone, 10 inches at a time, regardless of the type of unit.

The next zone is the Battle Zone, from 20 down to 10 inches from the enemy. Forces within this zone are within enemy artillery range, and will suffer accordingly.

A quick word on the sequence before we go on to the next zone. I use a simple alternate sequence, you-go/I-go, in which, every half turn, one side becomes the active or phasing player and the other the non-active or non-phasing side. When Side A becomes the active side, he moves and fires his troops using the direct fire procedures, thus inflicting hits on the enemy. But he himself, during his own active phase, receives hits, for if any of his units are within range of unlimbered enemy artillery, i.e., within the Battle Zone, they will take what I term Continuous Fire (CF) hits.

The next zone, extending from 10 down to 2 inches from the enemy, is the Combat Zone. Here, troops are within musket range of one another. Here, too, as Side A, the active side, moves and fires, his own units incur CF hits if there are either enemy unlimbered artillery or any deployed enemy infantry nearby.

The last zone, from 2 inches down to actual contact, is the Melee Zone, wherein hand-to-hand combat is resolved.

A Brief Summary

Melee Zone zero to 2 inches Hand-to-hand combat resolved.

Combat Zone 2 to 10-inches Troop's within musket range. Units take automatic CF hits during their active phase.

Battle Zone 10 to 20 inches Troops within artillery range. Units take automatic CF hits during their active phase.

Hostile Zone 30 to 20 inchesTroops outside the direct influence of the enemy.

Free Zone over 30 inches Free movement, no enemy interaction.

Approaching the enemy, entering the next zone down the line, requires a dice throw. Thus units, if their throw is unsuccessful, may balk at getting closer to the enemy lines, and may temporarily halt in their tracks.

Referring to the automatic CF hits listed in the above chart, what we have in effect in both the Battle. and Combat Zones, is a sort of continuous rolling fire kept up on all the forces on the table regardless of what phase you're in.

The thought is that even when Side A is the active player, Side B still keeps up a continuous fire, plunking roundshot and musket balls into the Battle and Combat Zones, respectively.

In our Napoleonic battle, we stipulated that for simplicity's sake, on a side's active phase, one battalion in each brigade would take an automatic CF hit. Each hit was represented by a marker, and 5 markers eliminated a battalion. This meant that the accumulation of markers from both direct fire hits and from CF hits was fairly rapid, and units could not simply stand in the affected zones too long.

One "cure" for a unit that had collected too many markers was to move it back into the Hostile Zone, outside enemy artillery range. In the Hostile Zone, by remaining immobile for one turn, a unit could remove a marker. Then, when it had regained its breath, it could resume its advance. Commanding the French left flank in our first game, I had to do this several times.

I had moved several units into the Battle Zone successfully (80 percent chance of doing so), and then found that they would not enter the Combat Zone (70 percent chance). So there they stood, with cannon balls falling all around them, collecting both CF and direct fire markers, until I declared: "Well, if you @#$%*&! won't advance, then you'd @#$%*&! better fall back."

Falling back into the next outermost zone is a freebee. Needless to say, my @#$%*&! units did this rapidly.

When advancing from one zone to the next, a single dice throw for the entire brigade decided whether or not the brigade was successful. The percentage chance was obtained by looking at the outermost distance of the zone and adding it to 60. Thus the Combat Zone extends from zero to 10 inches, and its outermost distance is, therefore, 10... add this to 60 and the chance of a brigade entering is 70 percent.

For the Battle Zone, going from 10 to 20 inches, the outermost distance is 20, and the chance is 60 + 20 or 80 percent. Note that the Hostile Zone's percentage is 90 percent... with a 90 percent probability of doing something, units can pretty much do what you wish in the Hostile Zone.

This same percentage applied to changing formation, facing, etc., in the various zones; it got more difficult, therefore, to deploy and maneuver the closer in the troops were.

One thing we discovered the first time out was that, with the additional hits incurred due to CF, the regular firing routines had to be somewhat modified. For example.; artillery started out with the ability to f ire twice (2 actions) and, in addition, when it used. close range canister, each time a battery went BOOM!, it put 2 markers on the target. Two fires with two markers each - PLUS the CF markers - were, obviously, too much in light of the 5-marker sudden- death rule. Units were disappearing rather rapidly. We quickly devalued the artillery.

First Scenario

Our first scenario set up a French attack on an entrenched British force. It didn't go at all well for the French, in part because of those awful British guns, going BOOM! and wiping out entire battalions at a single blast.

And in other sections of the battle front, where there were no guns to go BOOM!, we French had other problems, trying to convince our troops to advance to contact through the Hostile to Battle to Combat to Melee zones.

The percentage chance of going from one zone to the next could be augmented by adding points furnished by the Brigade Commander. Entering the Melee Zone, for example, nominally at 60 percent, the Brigadier could contribute 20 or so points, raising the figure to 80 percent. The Brigadier was then at risk for double his contributed points... in this case, 40 percent... and a dice throw of 40 or under laid him low.

The melee system tried out a somewhat newfangled, innovative, novel, unique, revolutionary, unusual and different technique. It's a variation of the Simon Gin Rummy Melee System which I've described in the past, and you're free to borrow it.

When an infantry battalion advanced into the Melee Zone to contact the enemy, both sides were handed a number of cards: a basic 3 for the battalion, and then 2 cards for each advantage, such as having a unit in support, or uphill, or behind works, etc. Usually, each side ended up with 4 to 6 cards.

The cards, which were played simultaneously, were of 2 types.

First, there were Fire cards. Play one of these and you got a shot at the opposition, following which his unit tested morale. If he failed the test, the melee was over... he retreated and you'd won. If he passed, the combat continued.

The second type of card was a number card; there-were about 15 of these. Each card had the number 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 on it. The objective was to play the card with the higher number, thereby winning the round. Winning the majority of rounds won the melee. Going back to the Fire card, if your opponent played one of these while you played a number card, and your unit took a hit and passed a morale test, then all you'd need to do was to show your number card, and you'd won the round.

It is fact that the Simon Gin Rummy Melee System (the dreaded SGRMS) has as much to do with simulating battle results and historical accuracy and realism as any other published method of melee resolution, and it's definitely more enjoyable.

All melee systems give you percentages, or points, or numbers, or factors, or some indicia related to the relative strengths of the units in combat. One then tosses the dice, using the given strength data to bias the throw. Here, with the SGRMS, we use the number of cards as the basic indicator of relative strength, and then, instead of relying on a random dice throw, we give the gamer, via the play of the cards, the chance to use his assets to one-up his opponent, a much more satisfying procedure.

I will admit it's more time consuming than the usual toss- the-dice system, but on balance, you're trading enjoyment for time, a not inequitable tradeoff.

Mod 2 Revision

Several Saturdays later, Mod 2 of the rules was presented. I set up a British attack against a defending French force of two small divisions. The ratio of attacking to defending brigades was 14 for the Brits, 9 for the French. That appeared to me to constitute a fairly balanced game.

On the field were 4 small towns, valued at 2 to 4 victory points each. And, as an afterthought, I also set out, for each side a Headquarters, and explained that if Headquarters was taken, then never mind the victory points, the battle was over.

In this second version, several key changes were made:

- a.6 markers instead of the original 5, were required

to retire a battalion from the field. This gave all

units a slightly greater longevity.

b.The artillery fire effect was greatly reduced... instead of firing like planet blasters, the guns now fired "normally", each battery now having the equivalent fire power of a battalion of troops.

C.And we instituted the "Hurst Cavalry Charge" (HCC) routine. Bob Hurst's cavalry, under the first set of rules, found. it impossible to close due to the requirement of having to stop in each zone. This zone-to-zone movement resulted in an overload of markers from both direct and CF fire piled up on the cavalry, so that by the time the unit made contact, the poor cavalry had virtually no poop left.

Cavalry now charged into contact from 2 zones out - from Battle Zone directly to Melee Zone - picking up only 1 CF marker in the process. I can report that General Hurst was more than satisfied with the HCC routine.

d.In the melee procedure, when the number cards were compared, instead of a simple "high number wins", each side tossed a 10-sided die and added it to the number displayed; the resultant sum was the critical factor, rather than the number itself.

Generals Hubig and Simon, in this second battle, (with the ratio of forces 14 to 9 against the defending British) commanded the attacking French forces. Or so they thought.

In command of the Brits were Dewitt and Hurst, who, evidently, were unaware of the meaning of "defend". Vastly outnumbered, they immediately went into the attack.

On the British left flank, the good General Hurst simply ate up all of General's Simon's troops. On the British right flank, General Dewitt easily kept General Hubig's forces at bay. And in the center, the British Brunswick Brigade, the dreaded BBB, having set out to break through the French lines and capture the French Headquarters, did so with relative ease.

So rapid was the British advance that most of the French forces never reached the center of the field. This proved decisive, for in melee, a defeated force had to retreat 2 zones, i.e., about 20 inches, and as we French lost melee after melee, the 20 inch retreat caused the losing units to run off the field.

This resulted in some accusatory discussion amongst the French staff:

- Hubig: M'sieu le General Simon, when you drafted these

wonderful rules, surely you took into account the

large retreat distance.

Simon: Oui, mon General, but I envisioned that our forces would be able to advance more than 10 inches from the table's edge before engaging the enemy!

Some people are never happy.

What truly helped the British advance was employment of the world famous "Exploitation Rule".

I wanted a lot of movement in the game; I dislike "static front" games... battles in which both sides face each other in midfield, and merely fire and fire and fire, with no virtual change in position over the course of the encounter.

Under the Exploitation Rule, when a unit won a melee, its Division commander was given an opportunity to advance an entire brigade a distance of 12 inches. The Division Commanders had been graded in the pregame setup procedures; the British Commander had an 80 percent chance of taking advantage of this rule, which he did, several times over.

This 12 inch advance was "zone free", i.e., the advancing units did not have to dice to pass through enemy zones of control as would have been necessary during the regular movement procedures. Nor did the units have to pay any terrain penalties. This permitted them to move up-field much more rapidly than ordinarily... which was exactly what I wanted.

In effect, the Exploitation Rule is nothing more than the equivalent of what other rules term a "breakthrough move" ... the object is to keep the game f lowing by giving an advantage to the side winning a melee. The theory, I assume, is that the opposition, having lost in combat, is momentarily a wee bit disorganized and off its feet, and the winning commander can take advantage of the situation by advancing his winning unit on the field, advancing it outside the bounds of the regular movement sequence.

The Exploitation Rule differs from normal breakthrough procedures in that it permits the Commander to bring up an entire brigade for the breakthrough move. Moving a unit into a gap is a far cry from moving an entire brigade into a gap, and we French found this out rather rapidly. The British Brunswick Brigade, in midfield, won, advanced, won, advanced, won again... both General Hubig and I liberally doused the Brunswickers, in markers... couldn't stop 'em.

Whenever a battalion was hit during the direct fire routines, it took a morale test. Each marker deducted 5 percent from the nominal morale level of 80 percent, and markers, if you remember, accumulated from both direct fire and CF sources. Another factor affecting a unit's morale level was the position of the Brigade officer... his distance to the unit under test was deducted from the unit's morale level. To balance this deduction, the Officer was permitted to add up to 30 percent to the unit's level, but his risk factor, i,e, the chance that he was killed, was twice the points with which he helped.

As the Brunswickers advanced, their Brigade Officer soon bit the bullet and was carried. off the field. Without a Brigade officer present, a unit suffered a negative 20 percent modifier to its morale level, and their base morale level went down from 80 to 60 percent. one would have thought that this alone would have deterred the Brunswickers.

But no. Despite the absence of their officer, despite the accumulation of markers (each deducting 5 percent), the Brunswickers came on and on and on. Generals Hubig and Simon fired and charged and fought and fired again...no use. There was no stopping the dreaded BBB. French-Headquarters were overrun...end of battle, end of game.

In games employing zones, I note that since zone-to-zone movement may almost be termed "symbolic", fewer problem areas seem to arise concerning the nitty gritty of who flanks who, who's within musket range, who retreats to where, etc. More later on this.

Back to PW Review February 1992 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com