For some time now, I've been massing a 30mm English Civil War (ECW) army. The types of figures include some good looking Staddens and Surens, but the bulk are "Stretchies", a rare series of figures unavailable on the open market. These Stretchies consist of a variety of 25mm Essex, Hinchliffe, and I-don't-know-what, which I have stretched to 30mm size.

The vast majority of today's 25mm figures, although breathtaking in the scope of the available poses and superior detail, all bear a distinct anatomical similarity to a race of squat, long-armed, ape- like orangutans. The sculptors, for some reason of their own, have designed the figures with the proportions of an undeveloped child: heads are oversized, torsos are squnched, and legs are short. The result is that most 25mm wargaming armies resemble a conglomeration of exceptionally well-painted dwarves.

Offhand, I can cite very few 25mm manufacturers whose figures' anatomy is anywhere near normal; CONNOISEUR is one, OLD GLORY is another... does anyone out there know of another?

The Simon stretching procedure, hitherto unrevealed to the general public, consists of one of two operations, depending upon the type of figure. In theory, the operation will transform a misshapen 25mm figure into a respectable looking 30mm figure. I will either cut the figure at the waist, adding anywhere from 1/4 to 1/2 inch to its height, or I will cut its legs at the thighs, adding an appropriate amount of "leg length" to it.

Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't, but the results are always interesting. Way back, for example, I took a Stadden Napoleonic officer, a British fella, who, I thought, could stand to grow a wee bit, and I extended his legs... unfortunately, just a wee bit too much. Today, Leftenant Wilt the Stilt still commands his troops, easily discernible on the battlefield because he stands head and shoulders over his counterparts.

And in the meanwhile, during this great gathering of 30mm figures, somewhat as a sideline, I have acquired a sizeable 15mm ECW army, enough with which to experiment while I develop a set of rules for the larger figures. I discussed this 15mm army in a previous REVIEW article (January 1988), in which I expounded on my thoughts concerning the first set of ECW rules I generated.

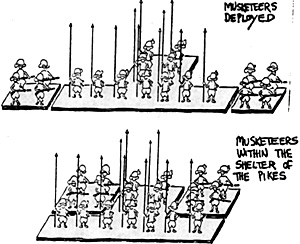

Amongst other things, I discussed the configuration of the pike

stand. Figure 1 is a reproduction of an illustration that appeared in

the January 1988 article. It shows that a stand of pikemen is in the

shape of a 'IT". Deployed musketeer stands extend to the side, and as

cavalry approaches, and the musketeers run for the shelter of the

pikes, their stands are placed in back of the crossbar of the "T."

Amongst other things, I discussed the configuration of the pike

stand. Figure 1 is a reproduction of an illustration that appeared in

the January 1988 article. It shows that a stand of pikemen is in the

shape of a 'IT". Deployed musketeer stands extend to the side, and as

cavalry approaches, and the musketeers run for the shelter of the

pikes, their stands are placed in back of the crossbar of the "T."

Lynn Bodin's group, in the northwestern sector of the country, tried out the rules and, en masse, all cancelled their subscriptions to the REVIEW. Lynn's summary of the rules procedures, published in the September 1988 REVIEW, was to the effect that his boys "considered the entire system a load of road apples". Another one of the terms he used was "unrealistic". A low blow... indeed, two low blows!

The northwesterners were bothered by the fact (I mention only one!) that the sequence was such that it was difficult to coordinate movement amongst units. This was, in part, a result of instituting movement as a function of "Command Points" (CP) ... CP were in short supply, and if you had no CP, you couldn't issue an order, and your troops couldn't move.

An even greater gut-wrenching factor for the northwesterners concerned the concept of the "impact marker". Units that suffered casualties were given a marker which temporarily decreased their morale level. Passing a morale test did away with the markers, i.e., they weren't permanent. This bothered the Bodin group. They could live with a roster on which losses were tracked, and better yet was removal of figures and casualty caps. If a unit was bumped and suffered casualties, then... BAM! ... clap a casualty cap on a figure. It's direct, it's visible, it's an obvious marker that the unit has been whomped, it tells all and sundry that the unit's been in combat.

But they couldn't get along with an "impact", the effects of which were transient and died out as the battle progressed. The current rules we're employing for the ECW use a roster system, with unit parameters recorded on a data sheet. The entire unit stays on the table - casualties are not removed - until the data sheet indicates that the disintegration point has been reached, at which time the unit is taken off the field.

And we're still using the concept of "Command Points". .. which imposes a built-in limitation on the force commander's ability to issue orders to his troops. Each turn, a number of Command Points (CP) are distributed to each side, somewhat proportional to the number of Brigade officers available. CP's are required to help in morale tests, to assist in melee, to order certain units to fire or move, to direct a number of pre- emptory actions... in short, CP usage is required when a unit faces an out-of-the-ordinary stressful situation and quick action must be taken.

An additional CP function concerns Scots units. I thought that the independence displayed by the Scots could be reflected in the game by imposing a requirement to control them via the CP, i.e., the need for the officers to continually ensure the Highlanders weren't going off on their own. Hence, whenever a Scots unit is issued an order to move, a CP must be expended... if no CP are available, a table is referred to, dice are thrown, and there is the chance that the unit embarks on its own frolic, and never mind what the officer wants.

Making up for the continual usage of CP on the Scots, however, is the f act that we give them an extra whomp on the opposition in melee. The Scots can hold their own with just about any unit on the field.

Two of my fiercest units are the regiments commanded by Captains McTushe and McNipp. These are "sword and buckler" men... they have no fire power, but in addition to their "plus" in melee just for being Scots, they get an extra plus against pike units. In a recent battle, the bold unit of McTushels Own, fighting for the crown and commanded by the good General Hubig, carved its way completely through the enemy lines and found itself so far ahead as to be isolated and surrounded by the Parliamentary forces. McTushe was eventually chewed up, but not before he had severely impacted on the Parliamentarians.

Card Sequence

The ECW gaming sequence is driven by cards: cards for "Royalist Move", cards for "Parliament Fire". "Rally", etc. All melees are fought immediately upon contact and here, too, a deck is referred to... in fact, two decks.

The first is called the Melee Deck; it determines the actions of which the melee is comprised. The second is the Impact Deck; it determines the effect on the opposition.

Upon contact, we draw from the Melee Deck... cards for "Defender Fire"I "Attacker Test Morale", etc., until a "Resolve Melee" card appears.

The rationale behind use of the Melee Deck lies in the fact that combat is resolved as soon as one unit moves into contact with another, hence the normal sequence does not permit any defensive fire. Here, the Melee Deck provides the possibility of the contacted unit getting off a volley and having the attacker test its morale before actually closing.

In fact, the Melee Deck even provides one card that states: "Defender may deploy and fire". This gives a defending unit, unhappily caught in the flank or in column of march, a chance to reform and blast away under the very nose of the surprised oncoming attacking unit. The probability of doing so is small... one card in the 12 card Melee Deck... but at least, it's there.

Melee Deck cards are drawn, the appropriate actions carried out, and finally a "Resolve Melee" card is turned up. Five of the 12 card deck are of this type, so what usually happens is that there's a flurry of fire by the defense or offense, a morale check or two, and then we begin the actual combat.

Now, lads, we come to the other deck I mentioned... the Impact Deck. First it was the Sequence Deck, then the Melee Deck... now the Impact Deck. I must mention that I have heard comments to the effect that Simon has gone absolutely ape on decks... but I ignore these remarks as coming from the Little People: little in mental stature, small in comprehensive ability, absolutely teeny-weeny in insight, and totally lacking in perception.

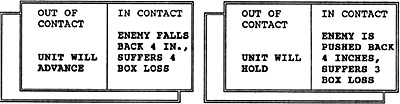

Now, having disposed of the Little People, let's get back

to the Impact Deck. Each card is divided in two: the right

side is used when the units are directly in contact. Two

sample cards are shown below.

Now, having disposed of the Little People, let's get back

to the Impact Deck. Each card is divided in two: the right

side is used when the units are directly in contact. Two

sample cards are shown below.

The right side results fall into three categories:

- Push the opposition back 4 inches, stay in contact, inflict losses.

Cause the opposition to fall back 4 inches, out of contact, inflict losses.

Hold position, stay in contact, inflict losses.

Cards are played alternately with the attacker going first, hence the defender, when it's his turn to play his first Impact Card, may find himself already driven back, out of contact. That's when the left side of the cards come into play. Here, there are two possible annotations:

- Hold position, or

Advance into contact

The defender, therefore, seeking to engage, chooses one of his cards which, on the left side, says "Advance", and he moves up into contact again. Now the attacker plays a card again, looking at the right side.

The result is that the front line of battle, as each card is played,, will tend to move back and forth in 4-inch increments. If you have enough "Pushback" cards, you can stay in contact, pushing the enemy back, inflicting losses as you do so. The opposition, of course, will try to play "Fallback" cards, forcing you to "waste', a card to advance into contact again.

Melee, therefore, is somewhat akin to a game of bridge as each side chooses its cards to best advantage. This is a "thinking man's melee", a mental exercise in tactics. Admittedly, this is not every wargamer's cup of tea... especially not for those who prefer a quick "toss the dice" routine. But it works. And more importantly, as the units surge back and forth, what we effectively have on the field is a representation of the "push of pike", until one unit breaks.

After all cards have been played, the winner is defined as the unit that last caused the enemy to retreat, either via a fallback or a pushback. At this point, the losing unit falls back another 4 inches, and takes a morale test to see if it retreats further.

This is how McTushels Own hewed its way through the Parliamentarian forces. McTushe's Own contacted a pike unit, which then drew three Impact Cards. McTushe, in contrast, first drew his own basic three cards, then another two for his Scotsmanlike attributes, and then yet another two since he was up against a pike unit... a total of seven Impact Cards.

For the first three cards, therefore, play was alternate, and then the pike unit having run out of cards, McTushe was free to play his remaining four. BAM! WHAMMO! BIFF! CRASH! The pike unit was driven back some 12 inches, McTushe staying in contact all the while.

This two-deck combat system, i.e. , use of a Melee Deck followed by an Impact Deck, is not the quickest method ever developed for melee resolution. It does take some time, and if you prefer to set up battles with the table loaded with units from edge to edge, you'll f ind your game will bog down. Our ECW battles tend to have less than a dozen units per side; more than this and you're in trouble.

Because of the time consuming "push of pike" melees, the procedures just described, i.e., those in which the Impact Cards are used, are restricted solely to infantry-versus- infantry affairs. For any type of combat in which cavalry are concerned, a quicky point-tallying system is used. Both sides add up their points: heavy cavalry units get 3 points, plus another 2 if they're on the flank, plus 2 more if the opposition is a musketeer regiment, etc., etc. Both sides then multiply their total by a 10-sided die roll, and the lesser product falls back and loses 4 boxes.

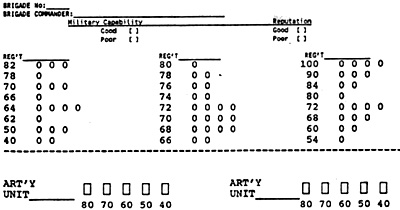

The losses referred to in the combat sequence consist

of crossing out boxes on a unit's data sheet. All regiments,

infantry and cavalry, each have a sheet as shown below, with a

maximum of three regiments composing a brigade.

The losses referred to in the combat sequence consist

of crossing out boxes on a unit's data sheet. All regiments,

infantry and cavalry, each have a sheet as shown below, with a

maximum of three regiments composing a brigade.

As boxes are crossed out, the morale level of the unit, noted on the left side of the regiment's listing, goes down accordingly. The average number of boxes assigned to a unit, i.e., the number of hits it can take before it disintegrates, varies from around 15 to 20. The morale levels also differ from unit to unit; I have several sheets made up, and one can never predict the starting level of a given regiment.

Artillery, i.e., one gun model, has a separate listing. A gun crew has only five boxes assigned; five hits and a crew flees the field.

The Command Point (CP) system is a tricky one to balance. The Sequence Deck contains two "Rally" cards, which, when drawn, permit both sides to replenish their CP. This is done via Command Point Cards (yes... yet another deck! ... is there no surcease to this madman's folly??'.

There are some 20 cards here, annotated as follows:

- 1 CP 8 cards

2 CP 8 cards

3 CP 4 cards

As the rules developed, we went through a number of exercises to determine the number of CP to be held, and their usage. First, we had only one "Rally" card in the deck. Then we gave out one CP Card per Brigade Officer. Then we ruled that anytime you wanted a unit to do anything, one CP had to be expended. Then we said that only ordering a unit to fire required one CP point. Then we maximized the number of CP Cards which could be held at any one time to seven. Each of these variations produced either too many CP, which made the whole concept meaningless, or too few CP, which completely bogged down the game, since units could do nothing.

Finally, we hit on what seems to be an optimum balance... when the "Rally" card appears, each side receives 50 points per brigade on the field, and for every 100 points, draws one CP Card. The CP are used to:

- a. Permit an officer to assist in a morale test.

b. Permit an officer to assist in melee.

c. order a countercharge.

d. Order pre-emptory defensive fire when being charged.

e. order artillery to fire.

f. Order a Scots unit to move.

g. Order a pike unit, when charged, to have its musketeers run to shelter.

ECW-ish

When I first considered setting down some rules for the ECW, I asked several people for input as to what the rules should contain to make them "ECW-ish". One specific result concerned the role that officers play... they should be quite active in the game, was the comment.

And so with our ECW command figures. Each Brigade Officer is graded in two categories: f irst is military skill, which enables the officer to attempt to assist in melee, i.e., he furnishes the unit with additional Impact Cards in combat. Second is his reputation, a parameter bearing on his contribution he provides to the morale level of his regiments.

Prior to the game, a simple 50% dice throw decides if the Brigade Officer's military skill is good or poor. If good, then, in melee, his units may add another two Impact Cards when they draw. If ' poor, however, there's only a 70 percent chance that he will be able to aid his unit; if he fails the dice throw, his unit loses one of its Impact Cards.

The same sort of procedure applies to the Brigade commander's reputation... he's either good or poor. If he possesses a good reputation, i.e., he's won his brigade's "Mr. Congeniality" award, he may add a maximum of 25 points to a unit's morale level. If, in contrast, he rates poorly, there's that 70 percent dice throw again... if he fails, he becomes a liability rather than an asset, and the unit's morale level decreases by 25 points.

Note that there's provision on the data sheet for the Brigade Officer's attributes.

Each time the Brigade Officer attempts to assist one of his units, he's at risk. For example, if he tossed in 20 points during a morale test, then the opposition throws the dice as follows:

- 01 to 10 The officer deserts, joins the opposition.

11 to 20 The officer is killed.

21 to 100 No effect.

Campaign

In one of our recent get-togethers, we set up a campaign of sorts, the intent being to gin up three associated battles which we could fight in one afternoon. Alas, I must report that too many details were omitted by the Campaign Commander (name withheld by request) in setting up the system.

There were three different fields, or tables, to each of which was assigned a basic force of around eight to ten regiments of cavalry and infantry. This number was chosen because of the limitations imposed by the ECW 15mm assets on my shelves. This provided an interesting unbalance of forces as each side assigned its musketeers, pikemen, dragoons, etc., to the three fields.

Dice were thrown to determine on which field the first battle would be fought. The three tables were linked by a road system, and to travel from one table to another required a certain number of game movement phases.

Remember that in the Sequence Deck, there are cards for "Parliament Move", "Royalists Move", etc., hence the entire bound is composed of several of these movement phases. What I didn't mention before is that the Sequence Deck also contains two cards for "Cavalry Movement"; mounted troopers, therefore, move not only on the regular run of Parliament and Royalist "Move" cards, but also on these additional cards.

After the first battle, when the surviving units set out for the second field, the additional cavalry movement phases meant that the cavalry arrived well ahead of the infantry.

During the battles, the usual questions arose: should cavalry be allowed to tromp, through woods? Should pike units be allowed to tromp through woods? And if so, and they contact an opposing unit, how much should their combat capability be degraded? How mobile should an artillery battery be? Would artillerists fight when an enemy unit makes contact, or would they run away, avoiding combat? Should we give an "evade move" to a cavalry regiment when it is approached by a much slower moving pike unit?

This sort of thing goes on and on and on... it always amazes me to find out, during the games we set up, how many areas remain to be covered, how many unforeseen situations can occur, how many surprises pop up.

One way to attack these problems is to use the method employed by the author of COLUMN, LINE & SQUARE (CLS). Each particular situation is noted, and a separate addendum to the rules is published. The resultant CLS rules book is, unhappily, almost 3/4 of an inch thick because of these additions.

The WRG Ancients people keep similar tabs on their rules... witness the very frequent quest ion-and-answer articles in the wargaming magazines. I have no idea of how thick the resultant "book" has become, but I wouldn't be surprised if the complete and unabridged Holy Tome weighed well over one hundred pounds.

Most of the questions have nothing to do with historical fact and reality, but with gaming mechanics. For example, the question of a cavalry unit "evading" an approaching unit of pike. Can the cavalry "evade"') Of course they can... the regimental leader raises his sword, shouts "Let's get outta here!" - or the ECW equivalent thereof - and the cavalry unit swings about and trots off, easily outdistancing the huffy- puffy pikemen.

But now we have the question... should they evade? or should we "force" a melee between the pike and the horse to quicken the pace of the game? It's all in the eyes of the beholder.

But I digress... back to the campaign. In the haste to set up the battles, the issue of control of the road systems between tables was somewhat uncovered and became a topic of discussion. Who could exit where? When? And, on arrival, could the entering forces be blocked?

Eventually, these pivotal issues were settled, and General Hubig, fighting on the side of the King, who had won the first battle on Table B, hurried his cavalry along the road system to reinforce the assigned units in the next battle, scheduled on Table A. The Sequence Deck, in addition to the normal run of "Parliament Move" and "Royalist Move" cards, contains two additional cards for cavalry movement only, hence the mounted units, during the bound (defined as one complete run-through of the Sequence Deck), will outdistance the foot troops.

The Royalist cavalry eventually entered Table A, appearing on the flank of the Parliamentary forces headed by Brian Dewitt. Lord Brian didn't even turn a hair; instead he made good use of the morale rules to nullify this potential flanking threat.

The ECW rules system borrows a page from an ancient and hoary set of Napoleonics rules, LE JEU DE LA GUERRE, espoused by none other than HMGS President Dick Sossi... so we know they're accurate, they're realistic, they're historically correct.

In the LA GUERRE rules, units do not normally test morale when impacted by fire or melee. Instead, each side is given a number of what are termed "pre-emptory morale checks", entitling them to point the finger at opposing enemy units during the battle, and to require these units to test morale. The number of these pre-emptory challenges is limited, and their use, if directed at units that have been severely hit, can be quite significant.

Whenever, in the ECW Sequence Deck card draws, a "Rally" card appears, then just as in LA GUERRE, one of the functions granted to the opposing parties is to permit them to point the finger at two enemy units, each of which must then test morale. There are two "Rally" cards in the deck, and these preemptory challenges... which arise in addition to the regular run of morale tests due to fire and melee... can be used to good advantage.

It turned out that the first Royalist cavalry regiment to enter on Table A was Lord Parke's Troop of Horse. Lord Parke's unit had been pretty badly banged up during Battle No. 1, and the cavalrymen's morale level, as indicated on their data sheet, was fairly low.

Each time the "Rally" card showed up, Lord Brian's finger pointed right at Lord Parke, and Lord Parke's troopers tested morale. Helas! Lord Parke's lads just weren't up to it... they failed time and time again, and each failure was accompanied by a fallback of 8 inches and a loss of one box on the data sheet.

The unit accompanying Lord Parke wasn't too far behind him... in fact, the entire set of reinforcements sent out by General Hubig from Table B and arriving on Table A, was not in the best condition possible... General Hubig was heard to utter several low-pitched and extremely un-Royal-like expletives as he found his men severely wanting in staying power.

Another interesting series of events during the battle on Table A concerned the dreaded McTushe's own, of which I have spoken before. McTushe and McNipp commanded sister "sword and buckler" units, fighting for the King and General Hubig. The General, well versed in McTushe's legendary deeds in combat, placed both Scots units in the very forefront of his line of battle, seeking to have them close with a Parliamentarian unit... in fact, any Parliamentarian unit would do, so eager were the Scots.

Lord Brian was also well acquainted with McTushe, having been on the receiving end of McTushe's claymore more than once. Brian's musketeers kept plugging away at McTushe, each volley knocking off from one to three boxes on the Scotsman's data sheet.

Firing Rules

A brief digression on the firing rules. These came from a set of modern armor rules developed by Tom Elsworth and me some thirteen years ago. ARMOR BOOM-BOOM was the name of the rules; you will probably not be surprised to learn they were not best sellers... even though Gene McCoy, editor of WARGAMERfS DIGEST (in which the rules were published) thought the technique was quite clever (dare I say "realistic")) . I can but pity the unreceptive wargaming world which must be hit on the head by a two-by-four before one can get its attention. The firing procedure used what we termed the "standard range" concept.

For the ECW scale, "standard range" for musket fire was defined to be ten inches, and for artillery fire, 20 inches. At the standard range, the probability of hit (POH) on the target was 60 percent per stand firing. At other ranges:

- For every inch LESS than 10, add 5 to the basic POH.

The maximum POH is topped off at 80 percent per stand.

For every inch MORE than 10, subtract 10 from the basic POH.

For those who are interested in such things, since the POH tops out at a maximum of 80 percent, this system gives a triple sloped POH curve, with zero slope at close range, and maximum falloff at the longer ranges as the POH falls to zero.

And so, on Table A, Lord Brian kept up his thumping of McTushe's Own, eventually reducing McTushe's morale level to the point where the Brigade Off icer, Captain Clancy, had to lend a hand to prop the unit up. But so many were the volleys heading McTushels way that Captain Clancy didn't last too long... he kept adding 25 points to McTushe's morale factor, placing him at risk for 25 percent, and eventually a low dice throw laid him out.

Without Captain Clancy, McTushe's Own couldn't hack it... for that matter, neither could McNipp's. A bad night for the Scots.

As I remember it, the second battle, in my mind, turned out to be a draw. I define it so because the Parliament/Simon/Dewitt ' forces were not completely wiped out by General Hubig. I have a fairly liberal viewpoint as to the goings-on on the table-top, and anytime I emerge with at least one surviving unit in a battle, I look at it as a draw.

And that, gentlemen, ends our first lesson in the machinations of the ECW. Rest assured that others will follow.

Back to PW Review October 1990 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com