So enthralled were Fred Hubig and I with the Ancients rules

we developed (see the outline of the rules in the December 189

issue of the REVIEW), that we decided to use 'em in a simple

campaign. The territorial map we employed was stolen from

either THE SOLDIER KING or A HOUSE DIVIDED, or both.

So enthralled were Fred Hubig and I with the Ancients rules

we developed (see the outline of the rules in the December 189

issue of the REVIEW), that we decided to use 'em in a simple

campaign. The territorial map we employed was stolen from

either THE SOLDIER KING or A HOUSE DIVIDED, or both.

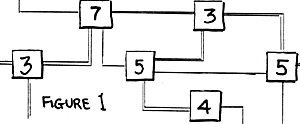

The map consists of a number of junctions connected by a road system. A representative portion of the map is shown in Figure 1. Dual lines indicate a main "highway"; single lines are regular roads. Each junction has a value indicated by the number within its box.

The campaign sequence is an alternate one, and each turn, instead of being able to move all the forces we have on the map, we can move only the forces located at two junctions. These forces may break up... they don't have to move to the same destination... and as they break up, then, due to the "two junction" restriction, it becomes more difficult to coordinate movement of the entire army.

Movement is further restricted by the road system itself. Each turn, the dual line "highway" can be traversed by a maximum of 100 Army Points, while a regular road can handle only 50 Army Points.

Each side started with 500 Army Points (AP) which could then be split as desired into various field forces. The army is headed by a Commander In Chief (CINC) and five Field Commanders, each of whom plays a role in the battles.

As the battles progress, the campaign rules are modified to clearup certain problem areas as they arise. As an example, the victory conditions were originally set forth as follows:

- a.Every unit on the field gives rise to 10

Victory Points (VP), hence with 10 units,

you get 100 VP.

b.For each melee loss or morale failure, subtract 7 VP from the total.

C. When the VP total reaches zero, there's a 60 percent chance that the force surrenders.

d.If the force does not surrender, then every subsequent melee loss or morale failure increases the chance of surrendering by 10%.

Our first battle pitted two equal forces of 100 AP against each other. I had 15 units, giving me a starting value of 10x15, or 150 VP. By the time my VP went down to zero, and I rolled to see if I gave up the field, my poor decimated force had only 38 AP left, a 62 percent attrition.

We decided this was way too much of a wipeout, and for subsequent battles, Rule (b) above was changed; we now subtracted 10 VP for a melee loss or morale failure. In so doing, the VP total falls to zero more rapidly than before, so that there's more of your force left at the time you take your "Do you surrender?" test.

Although we move Army Points om the map, the actual value of the forces are not disclosed. Instead, we use a method suggested by Bob Wiltrout some time ago, which gives only an approximate indication of enemy force size. Forces are tagged with one of five letters:

- Class A 0 to 40 AP

B 41 to 80

C 81 to 120

D 120 to 160

E Over 160

The intent is to prevent two forces of disparate size from meeting, resulting in a wipeout of the smaller. If, for example, my 100 AP force (Class C) attacks a Class C enemy force, I know that at best, I outnumber the enemy by 20 points and, at worst, he outnumbers me by 20 points. The 20 point difference can give rise to an advantage of several units, but not enough to decisively determine the outcome beforehand.

Each of the five Field Commanders (FC) is given two types of point values:

- The FC starts the campaign with 80 Army Morale

Points. These are brought into play when, during a

battle, the force's VP reaches zero. The FC can step

in and use some of his Army Morale Points to reduce

the 60 percent probability that his force will

surrender.

Note that the FC's Army Morale Point total of 80 is not replenished. The So points must last the FC for the entire campaign.

Prior to each battle, the Commander dices for a number of Unit Morale Points. These points are used to assist individual units in taking their morale tests when casualties are incurred. Unit Morale Points are assigned according to the following chart:

- Dice

01 to 33 50 points

34 to 66 75

67 to 100 100

If, for example, the Force Commander has 75 points, and he assists one of his units, which has a 65% morale factor, with 20 points , then the unit morale level rises to 85%. The Commander's point allotment is decreased, not by just the 20 points given to the unit, but by the following:

- Decrease = (Points given to unit) + (Distance of Cdr to unit)

The further the Commander is from a unit, the more difficult it is to assist it. Placement of the Command figure on the field thus becomes critical so that his point expenditure is minimized.

As an aside, the latest COURIER (Vol IX, No 1) carried an article by John Boehm - Ancients editor - which described numerous campaigns in which he had participated. The article read well, as John described his various campaign adventures... he specifically mentioned eight efforts and referenced others... but the eye opener came in the following statement:

- "One might well ask what were the actual

outcomes of the various campaigns. Alas, I

must admit that they simply never reached a

conclusion for one reason or another all simply faded away. Perhaps interest waned

due to the length of time between various

game turns, or in some cases key players

were unable to participate, or moved out of

the locality."

John is not the Lone Ranger. Our group, too, has embarked on campaign after campaign, each of which has fizzled due to... what? Is there a genetic deficiency within each wargamer, preventing him from seeing a campaign through to the bitter end?

Simple campaigns, complex campaigns, campaigns with lots of logistics, campaigns with little or no bookkeeping... they all whither and die on the vine.

About the only continuing success we've had is with the "one afternoon's campaigning effort" ... one day affairs in which, say, three quick battles are ginned up and each of the engagements can be decided in the period of an hour or so.

And so it well may be that this current effort will also dry up and blow away. Thus far we've had three battles, in two of which there were 100 Army Points (AP) per side, while in the third, I was outnumbered 100 AP to 65 AP. Forces were chosen according to the following list of "per unit" costs:

- Hvy Cav10

Hvy Inf 9

Phalanx 8

Med Cav8

Med Inf 7

Chariots 7

Lt Cav5

Lt Inf 3

Elephants 6

Note there's a distinction between the phalanx and heavy infantry. The rules give the phalanx the edge over heavy cavalry, which, in turn, usually whomps heavy infantry.

I tend to purchase cavalry-heavy forces, but I haven't really been successful with them. Loads of cavalry are stationed on both my flanks, and the problem is that the remaining points permit only a token number of infantry units to hold the middle.

Unit morale level is the key factor in the game. In melee, if the unit on, say, Side A, loses, it falls back in disorder and requires one full turn to recover. Usually it never gets that full turn, for a victorious Side B enemy unit can, via a number of "Command Points", be issued orders to immediately breakthrough and pursue.

A similar number of Command Points can then be issued by Side A in an effort to intersperse a unit between the advancing victorious force and the cowering, disorganized unit. More often then not, however, Commmand Points to issue such an order are not available... having been used up in the issuance of prior tactical orders.

If no protecting unit can be ordered by Side A to interdict the advancing group, then B's unit contacts the disorganized A unit which then takes what we term a "stress morale test" ... at half its current value, which usually equates to a 30% to 40% chance of success. A failure here indicates that the troops are swept from the field.

You can see that a win in melee, coupled with a quick follow- up and pursuit, usually results in the annihilation of the target unit. The Command Point system mandates, therefore, that a reserve be kept... a second line of troops which can be called upon to intercept and halt an enemy breakthrough. And note that not only do you need the reserve, but you need the Command Points to issue the orders to the troops to get them moving. One without the other won't work.

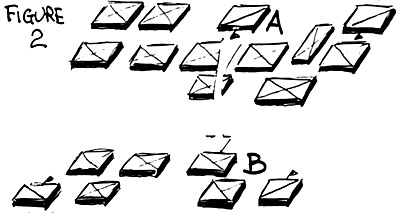

Due to the fairly extensive and sweeping movement in the game (cavalry can charge 30 inches)/ one item of debate that arose concerned the extent of the charge and preemption moves.

For example, in the diagram below, cavalry unit A announces a charge on infantry unit B.... the question immediately arises: can unit A "go through" its owned formed infantry lines to reach B?

Remembering that the scope of the game is "more than

tactical" and that the time span of a single turn is in terms

of hours rather than minutes, it was decided that such a charge

was possible.

Remembering that the scope of the game is "more than

tactical" and that the time span of a single turn is in terms

of hours rather than minutes, it was decided that such a charge

was possible.

Here, we decided that there was sufficient time within the bound to permit units to get out of the way... how they actually maneuvered and sidestepped and formed and reformed was not our concern... all we were concerned with was the fact that the scale permitted such maneuvering.

In all the rules I've toyed with, there's usually some sort of Morale Point or Army Point or Command Point system by means of which the Force Commander is given the ability to assist his troops. The number of points so assigned is limited, and the Commander is forced to allocate his finite resources.

Sometime ago, I discussed this with Bob Wiltrout, RHGE [Realistic Historical Gamer Extraordinaire], who asked:

- "As the number of these so-called Command Points

decreases, just what exactly is the commander using up?"

"Well... uh... gosh, Bob... it's like..."

"What asset is actually diminishing in value?"

"Um... well, I ... you see... er...

"Did Wellington or Napoleon have some sort of capability that, as a battle wore on, decreased with time?"

As you can see, Bob was attacking on all fronts, and I had few Command Points to stop him. All I could offer in rebuttal - aside from a number of glottal stops - was that the Commander's "energy" was decreasing as the battle wore on... that his staff of adjutants, by means of which he issued his orders, was decreasing due to mounting losses... and that, because the Commander couldn't be everywhere at once, he could devote his attention to only one part of the field at a time, with subsequent loss of control over the other sectors.

Although there's a thread of logic in this concept, the main purpose of the Command Point system is to give the command figure "something to do" ... it is, essentially, a gaming ploy whereby the gamer not only has his troops on the field to maneuver, but he's got a backup asset, a reserve, into which he can dip to support the troops.

In many sets of rules, the commander only plays a part when he "attaches" himself to a particular unit. The blessed unit then gets a +1 on its morale level, a +1 on its combat capability, and so on.

To tell the truth, I'm not sure that any of these systems wherein the presence of the command figure bolsters a unit's effectiveness - really portrays what went on on the battlefield. Couldn't the commander's presence have triggered the opposite reaction: "Hey guys, there is the @#$%!&* that got us into this!" ... whereupon the commander is greeted by a shower of arrows, or a hail of javelins, or a blast from an AK-47.

Sometime ago, I generated such a set of rules. Both the force and unit commanders had to carefully tiptoe about their troops, trying not to draw thier attention. Perhaps, someday, I'll tell you about it.

But back to our campaign

Our third battle, fought on the Plains of Sestos, proved the most interesting. Here, Ubigsop the Uberper I s 100 AP force attacked one of mine, a 65 AP force commanded by Sebacious the Oily.

Ubigsop had 15 units on the field... at 10 points per unit, he thus started with 150 Victory Points (VP). Sebacious' 65 point tally gave rise to 9 units, or 90 VP. Remember that each "bump" (a loss in melee or a morale failure) taken by a side reduces the VP total by 10, and that when the VP reach zero, there is a 60% chance the force surrenders.

Brian Dewitt commanded Sebacious, small cavalry contingent, and one unit in particular earned a reputation for valor and glory. This was the Chetite Light Cavalry force, which got behind enemy lines and, like the Scarlet Pimpernel, seemed to strike everywhere at once.

Ordinarily, light cavalry is powerless against heavier units unless it can impact on the flank or rear of a selected target, at which time it forces the dreaded "stress morale" test, at half the normal morale level. The Chetites proved devastating... the unit started out at 7 Strength Points (SP) , and at battle's end was barely hanging in there with only 1 SP left, but Brian's judicious use of his Command Points kept the Chetites going.

Just as the Chetite Light Cavalry won the trophy as most valuable on the side of Sebacious, Ubigsop had a similarly honored unit... the Blue Heavy Infantry.

The Blues always lead Ubigsop's advancing forces... they want to be the first to contact the enemy... how else to win glory?

In the forefront of battle as they are, the Blues tend to ignore their flanks and rear, assuming, I suppose, that their fellow units will support them. On more than one occasion, I have taken advantage of this, and my cavalry, sweeping in from the side, has plowed into the Blues... one would think this would cause a certain amount of consternation in the ranks.

But no!! ... each time, the disadvantaged Blues have:

- a. Laughed most heartily, while easily passing their

stress morale test, and

b. Absorbed the shock of the charging cavalry (a unit that impacts on flank or rear gets "first hack" at the enemy) , and

c. Struck back in their off-balance condition (the unit that is hit on flank or rear will - if it passes the stress morale test - strike back only at half value), and

d. Completely pulverized the attacking cavalry unit and sent it fleeing!

e. Having disposed of this momentary distraction, the Blues were then free to reform and continue their assault on my front lines.

Towards the closing moments of the third battle, Ubigsop the Uberper was a wee bit nervous. Remember that he had started out with 150 VP, while we commenced with 90. By dint of good fortune... and the help of the Chetites... we had whittled away at his 150 VP, and we both stood at 20 VP. This meant that two more "bumps" on either side would force the "Give up?" test.

Alas, our depleted units couldn't keep up the pressure, and Ubigsop pulled it out... a costly victory.

Back to PW Review January 1990 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com