Some time ago, our group looked at a skirmish reaction game in which a unit's response to an impact from fire, melee, etc., was determined by reference to a chart. This was a direct result of some experimentation with single figure reaction rules which I authored for THE COURIER and which appeared in the REVIEW of September 1985.

Some time ago, our group looked at a skirmish reaction game in which a unit's response to an impact from fire, melee, etc., was determined by reference to a chart. This was a direct result of some experimentation with single figure reaction rules which I authored for THE COURIER and which appeared in the REVIEW of September 1985.

Two items prompted me to take a new look at the reaction game: first, a new subscriber to the REVIEW, Eric Ackermann of Williamsburg, Virginia, had offered some thoughts on the subject. Second, Tom Elsworth came across the Atlantic to spend a pleasant holiday with me, and I wanted to get his input on the concept. And so a couple of games were set up, with Fred Haub and Fred Hubig participating.

The reaction game is essentially a morale game; we remove no figures and the effect of an impact shows up as a permanent decrease in morale level. Several such decreases and the unit is termed too ineffective to function properly, and is removed from the field.

The basic problem with the rules system as developed concerned the extended length of the turn. For example, if Side A had three units, A1, A2, A3, as did B with B1, B2, B3, and A1 fired on B1, a reaction cycle would be set up between A1 and B1 until one of them quit. There are nine such combinative cycles... A1 vs B1, B1 vs A1, A2 vs B1, B1 vs A2, etc ... and the number of cycles increases geometrically with the number of units involved.

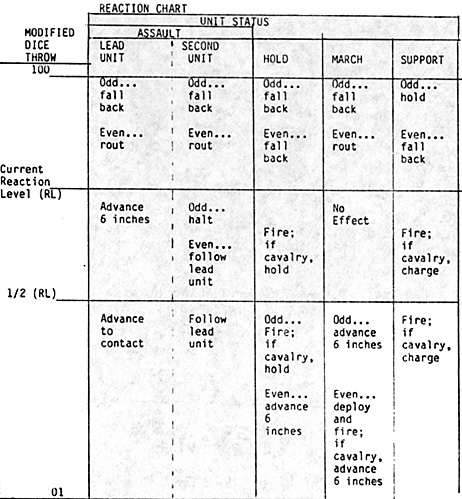

Shortening the cycle, therefore, was the objective of our latest exercise and after a couple of games to get the juices flowing, we decided that, every turn, prior to moving his forces, each commander would categorize his units as being i n one of four modes:

- ASSAULT... Here, two units were banded together to contact the enemy. Only the first, the leading unit, would directly test its reaction to an impact. The second, following, unit tested to see if it would follow the first. A unit could not be in the ASSAULT mode unless it was within one move of the enemy.

HOLD... These units would stand, defending a given position.

SUPPORT... These units were assigned protective supporting functions. A cavalry unit could charge if the enemy, threatening other units, entered the charge zone of the cavalry. An infantry unit could fire if the enemy came within fire range.

MARCH... These units were either in line or march column, attempting to move on the battlefield. Their reaction is more "sensitive" to an impact than units in other modes; a unit in march column is less likely to have time to be able to deploy and fire when a threat appears than when it is in HOLD or ASSAULT status, hence it receives a -10 on its reaction check.

The sketch is taken from one of our test games... an American Revolutionary War battle consisting of an assault on Fort Peck, held by the British - commanded by Fred Hubig, whose description of the battle follows this article. The reaction cycle can be more easily explained by a brief description of what happened in this sector of the field.

Here, a combined force of American Regulars and colonial militia, 40mm jobbies from my own Distorted Toy Soldier Laboratory, some 11 5-man units, gallantly stormed the walls of Fort Peck and caused the British to flee.

The south-west corner of the fort was defended by several British infantry units as shown, all in HOLD status. The American 1st Brigade, two regiments, was assigned as an ASSAULT unit, ready to scale the walls.

The American 2nd Brigade, to get to its position to assault the west wall, was formed in MARCH mode since the creek didn't give too much room for maneuver on that side of the fort. The 3rd Brigade, on the far side of the creek, was placed in line in SUPPORT status to provide covering fire in case the British cavalry to the north charged the marching 2nd Brigade. The action can be broken into several segments:

- a. The 1st Brigade's assault, Regiment A leading, followed by Regiment B. Both regiments charged and were placed 6 inches from the wall, i.e., in the British threat zone, and the defending British tested their reaction to being charged... it failed by rolling a 95, and fell back. The wall in front of the assaulting troops was unmanned and Regiment A had a 70% chance to scale it, which it did. Regiment B tested to see if it followed A, and was also successful

Regiment A now found itself in the threat zone of another British unit, which tested its reaction. This unit fired, and Regiment A's reaction - the result of a high dice roll - was to run. Regiment B, a good follower, followed. The assault of the 1st Brigade ended ingloriously.

b. The 2nd Brigade, Regiments C, D, and E, reached its position; C and D formed an ASSAULT team with C as the leading element. E remained outside, forming line to HOLD in case the British cavalry charged.

Regiment C was placed 6 inches from the walls, D right behind it, and after a series of reaction and re-reaction dice throws, Regiment C gained the walls. General Hubig's Brits were plagued with very high throws throughout the battle, and here, his defending unit fell back rather rapidly.

Regiment D, due to a poor dice roll, did not follow C, and was not available to help out when the British counter-attacked. Three separate units converged on C. In response, Regiment C was given three separate reactions, one to each attacking unit. It turned out that it fired on one, charged one, and fled from the third. Of the latter two, which were in conflict, we took the worst result as the most probable, and so C, after firing, abandoned the walls of the fort.

c. While the above was going on, the British cavalry finally decided to charge from their northern post and descend on Regiment E. They were placed in E's threat zone i.e., 6 inches a,-.;ay, and two reaction tests occurred simultaneously.

First, E itself tested; the dice roll, a low one, stipulated an advance on the horse! Stout fellows, the men of Regiment E.

The second test concerned the 3rd Brigade, designated the SUPPORT unit. Here, the 3rd Brigade's reaction, when the cavalry came within its fire zone, was to blast away at the horse. Between the fire of the 3rd Brigade, and the resolute stand of Regiment E, the cavalry, when testing its reaction to close, took to its heels.

The unique thing to be stressed about the above is that every one of the actions described was mandated by a series of dice throws and references to the reaction charts. All we did, as the British and American Commanders, was to place the concerned units in the appropriate threat zones, "wind 'em up", and follow the charts.

Of interest is that we partially solved the problem of extended turn length by resolving reactions in terms of groups of units instead of one by one.

Since figures are not removed during a morale game, the action will tend to go on and on unless some sort of victory or defeat condition is imposed on the commanders. Here, we gave Defeat Points (DP) to each side as follows:

- Regiment falls back: 1

Regiment routs: 4

The British, with 8 brigades of 2 regiments each, were given a defeat threshhold of 32 DP (an average of one rout per brigade). If the Brits reached 32 DP, the battle was over, General Hubig would turn over the fort, and his men march out with full honors.

The American force, larger than the British, had a DP threshhold of 44 DP.

As I indicated earlier, a series of abysmal dice throws on the part of the British led to their defeat of 32 DP while the Americans had totaled only 21.

Back to PW Review November 1987 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com