It is fact that SAE 30mm figures are not things of beauty. They are skinny, they are misproportioned, they're made out of brittle pot- metal, they have no detail. They are, in a word, ugly. They were popular about two decades ago when their price was within reason, but, of late, they show up more and more at toy soldier shows as collector's items at $30 to $40 per box of ten figures. Those who pay such prices fully deserve what they're getting.

Somehow, Bob Hurst recently came up with around 300 SAE 30mm American Civil War figures... he discovered a source of painted figures at fairly reasonable cost, i.e., "wargame", rather than "collector" prices.

Seeing Bob's uglies arrayed on his 6 foot by 12 foot table, I immediately thought of my own ACW 30mm collection, composed of uglies - like Bob's - plus an assortment of Blue and Gray Scrubies ... who are not that much better looking ... a little over 200 figures.

I challenged Bob ... his entire horde of Blues and Grays against mine. Brother against brother Blue against Gray Blue against Blue father against son, etc., etc the Lion's Federalists against the Hurst Unionists. Both fighting for the Union. Solidarity forever. So much for historicity.

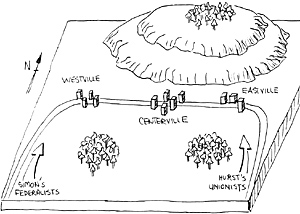

Fred Haub chose the scenario for our first battle out of Charles Grant's book: a meeting encounter in which the field looked as shown on the map. The basic objective for both sides: capture Centerville.

The initial dispositions were similar in nature:

- a. First, we divided our forces into three Divisions.

b. Second, we each threw a 10-sided die and multiplied by 10. This was the number of inches we were permitted to set up from our entry points with the First Division of our force.

c. Next, the Second Division would issue forth on Turn 3 from our respective towns ( Westville for me, Eastville for Bob).

d. Finally, the 3rd Division would enter on our entry points via the roads, on Turn 5.

Under Step (b) above, I threw a 4 for 40 inches, and Bob a 6 for 60 inches; this gave him a 20 inch incursion advantage which he emphasized by placing four cavalry units in his First Division, giving him a fairly mobile front line force.

The evolution of the sequence is interesting; it took some time and developed ,over a number of battles. It is, in fact, still going on. It can be divided into five phases as detailed below. We were quite aware of the ON TO RICHMOND system in which units moved by brigades, but the intent was to explore other types of systems.

- a. Phase A was a simple You-go/I-go affair, but, somehow, this

didn't produce enough "surprises".

b. Phase B used a card deck in which was listed every unit on the field. Each infantry regiment had its own card, while every cavalry regiment had three, thus making the cavalry more fluid than the foot troops. This type of sequence prevented any inter- regimental coordination, since each regiment moved off on its own, independently, when its card was drawn.

c. Phase C produced a deck in which, on each card, were listed several specific units, not necessarily in the same brigade. The regiments so listed could, therefore, coordinate their actions to some extent but cooperation was minimal.

d. Phase D began the first of the true coordination sequences. Here, each side was given four types of brigade commanders, each of whom had a certain number of cards in a command deck:

- Rash 6 cards

Average 5 cards

Cautious 4 cards

Poor 3 cards

Thus Rash Brigadiers moved and fired their troops twice as efficiently as Poor Brigade commanders in a ratio of 6 to 3. When a card was drawn, each side diced to see who moved or fired first. If Rash commanders were to move, and Side A won, then all of A's Rash Brigadiers' troops moved, after which Side B went, and a new card was drawn.

e. This phase also categorized brigade commanders into Rash, Average, Cautious and Poor. Here, orders were given to each regiment in a brigade; there were three types of commands, which, in order of Aggressiveness, were:

- Position troops moving, reforming,

refacing

Fire stand off and fire

Attack attempt hand-to-hand combat

Dice were thrown for the most aggressive command given to the units in a brigade and the following chart told how-many regiments in the brigade were caught up in the aggressive order and HAD to obey. Those units that didn't have to obey could carry on as usual.

| Dice Throw | Number Of Units That Must Obey The Most Aggressive Command |

|---|---|

| 01 to 30 | One regiment |

| 31 to 65 | Two regiments |

| 66 to 85 | Entire Brigade |

| 86 to 100 | Next Aggressive Command |

Examples

Here are two examples to show how this last table works:

- a. in a three regiment brigade, the 1st is ordered to fire,

and the 2nd and 3rd to move up and deploy. There are two types of

commands here: one is "Move", the other is "Fire", hence the Most

Aggressive Command, termed the MAC, is "Fire". The dice are now

thrown; a 47 results: two regiments in the brigade MUST fire, and

not just the 1st Regiment alone. The commander may choose either

the 2nd or 3rd as his second firing regiment.

b. Same set-up; the lst is to fire, the 2nd and 3rd to move up. The MAC here is, like the first example, "Fire". The dice are thrown--a 92 results, indicating that the Next Aggressive Command is called for. After "Fire", the next aggressive command is "Attack", and so now we refer back to the chart, and roll the dice again for the new "Attack" command: a 45... two regiments MUST charge forward. No longer can the lst merely stand and fire ... but it, and one sister unit, must attempt to close.

What has happened in example (b) is that an order to firefight has now escalated into an allout attack on the enemy position.

The type of commander affected whether or not things got out of hand; the dice throw was modified as follows:

- Rash +20

Average 0

Cautious -10

Poor -20

A Rash commander, therefore, went "up" on the table, his aggressiveness in sharp contrast to that of a Poor commander, who often couldn't even coordinate the movement of his entire brigade.

Our orders of battle were, roughly, as indicated below. Infantry and cavalry regiments had from 6 to 12 figures, while guns were manned by three figures.

| Unit | The Lion's Federalists | Hurst's Unionists |

|---|---|---|

| Infantry Regts | 9 | 13 |

| Cavalry Regts | 3 | 6 |

| Guns | 3 | 3 |

The readership will not be surprised to note that we had never played the rules system before... the simple reason being that, one week before, we had tried out some of the new procedures and in the interim, I had put out an "up-dated" version on paper, and in the process, changed most of what we had done the previous session. Never let it be said that moss grows under our rules. About the only thing in common with the procedures generated during the first go-round was that we used a roster system.

Each unit staffed out with 200 EFFECTIVENESS (E) points. The unit's morale level was half its E point value, so everyone commenced with a perfect 100%.

A regiment firing its muskets would "range in" on a selected target by throwing a 10-sided die. The muskets reached out to a distance of:

- Range = 3 x Die Roll

If the musket fire reached the target, then one E point for every man firing would be deducted frorn the target's value. Ten men successfully firing against a fresh 200 E point unit reduced it to 190 E, and a morale test at a level of 190/2, or 95%, would occur.

Artillery range was ... 10 x Die Roll, giving the gun a maximum range of 100 inches. Here, we used a range factor... defined as the ten's digit of the range measurement.

Points deducted from target: (Number of Gunners) x (4 - Range Factor)

Assuming a gun successfully ranged in on its target, say at 23 inches where the range factor was 2, then a 3-man gun crew would score:

- (3 gunners) x (4 - 2), or 6 E points

At very long ranges, the expression (4 - Range Factor) was not permitted to go negative; its minimum value was 1 as long as the gun ranged in; hence 3 gunners always knocked at least 3 points off their target's E points if they hit it.

To prevent units low in E from hanging around forever, long after their effectiveness was so reduced as to render them useless, and, in general, making nuisances of themselves far out of proportion to their actual status, we instituted the "take-'em-off-the-board" rule: when a unit's E points fell below 100, i.e., less than half the initial value, there was a chance that the unit disintegrated completely. This was a function of how far below the 100 point disintegration threshhold the unit had reached:

- Chance of Disintegrating = 3(100 - E points

One gaming ploy which our group incorporates in just about all our rules sets - regardless of era - concerns unit officers and the role they play in spurring their men on. In the 30mm Civil War, every regiment and battery was assigned an officer who was permitted to contribute points to his unit's morale total to help it pass its morale check.

If, for example, the Fighting 999th was fired at, was required to test morale, and had 130 E points left, its morale level was at 130/2, or 65%. The Regimental Commander could temporarily contribute, say, 30 points, giving the 999th a 65+30, or 95% morale grade, making it quite easy to pass. He could, if desired, give 35 points for a total of 100%, thereby ensuring that it would hold position. He could, in fact, give any number of points.

The penalty for this allocation of points by the officer was that the officer himself was at risk of being killed. His risk factor was twice the number of points he contributed, e.g., if he helped out with 30 points , there was a 60% chance he'd keel over. The decision must be made , therefore, as to how important it is to hold a unit in place compared to the fact that if the number of allotted points is too high, and the risk factor too great, the officer might not be around for the second try.

In our first battle, my Federalist force managed to place one regiment, led by Major Gold, on the hill to the north of Centerville. Major Gold did fine work; his unit was the repeated target of Unionist fire, was slowly being whittled down in E points, and the Major continually threw in 20 to 30 point augmentations to help the regiment out... and he survived!!

Not forever, of course, for risk factors of 40 and 60 percent, each time his unit took a casualty led to his downfall. And when the Major fell, so disheartened was his unit, that it broke during the very next firefight and routed off the hill.

The rout of Major Gold's regiment signalled the end to me; I withdrew and the Unionist flag flew, undisputed, over Centerville.

The Lion of Ostlandt, Major-Domo of the Federalist Armies, is not one to take a defeat lightly, however, and he immediately unearthed a quantity of fresh 30mm ACW Scruby soldiery buried deep within his basement armory. A dip in the blue bucket, a dip in the gray bucket, a dab of flesh, a touch of silver for the gleam of bayonets ... PRESTO!... three more Federalist forces to take the field to fight the Unionist oppressors!

To date, we've fought about seven battles in the Great 30mm Civil War, gradually shaping the rules into a set with which we'll be happy. Happiness, of course, is a relative term... we expect, and receive, lots of "what if..." and "suppose we..."

One of the latest "suppose we..." changes is to deduct E points whenever a regiment sees a fellow unit routing. It's not much per rout, but in the course of a battle, a regiment, seeing a half dozen supporting units rout, has its morale level eroded as unit after unit of friendlies takes off.

This rule has had an interesting impact on the battles. Called the "everybody's watching!" effect, a regiment that routs is definitely stigmatized if it does so within full view of the rest of its division. Every unit in the division knocks off a couple of points and the men therein jeer and catcall as the fleeing unit goes streaming past.

All the above may, or may not, be seen as logical, rational, sensible, and historically applicable by the readership, but, as for our PW group, it keeps us quite busily occupied and off the streets at night.

Back to PW Review March 1987 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com