Bob Liebl is currently developing what he terms a “grand-tactical” set of Napoleonic rules for 15mm figures. The scale is such that the maneuver element is the division, composed of some 10 stands.

Bob Liebl is currently developing what he terms a “grand-tactical” set of Napoleonic rules for 15mm figures. The scale is such that the maneuver element is the division, composed of some 10 stands.

I’ve played in two consecutive versions of the rules, and in each game, I was given command of a corps. In the first encounter, my Bavarian corps had 5 divisions… 4 infantry (around 12 stands each) and one cavalry (6 stands). In the second battle, my command consisted of a Polish corps… 2 infantry, each of 12 stands, and 1 cavalry, of 6 stands. Each infantry corps had its own artillery battery, represented by a single gun model.

For brevity, I’ll term Bob’s rules LIEBL’S GRAND TACTICAL (LGT). The scale is such that in LGT, musketry extends out to 2 inches, which gives a ground scale of approximately 1 inch to 100 yards. I would have thought that with an entire division as the gaming element, the scale would have been even greater, and musketry completely subsumed into the combat phase.

Each complete turn of LGT takes one hour of battlefield time, and consists of several phases.

First, there’s an order-giving phase. The army commander dices to see if he issues his orders. This is followed by each corps commander dicing to see if the orders were received. In my Polish corps, led by General Poniatowski, the general’s chance of successfully receiving and understanding his orders was 60 percent. And then, after Poniatowski got his orders, each of my division commanders did their own dicing. My two infantry division commanders were deemed “poor” and each had a 50 percent chance of understanding what was going on, while my cavalry commander was “mediocre” and was up to 60 percent.

Needless to say, this could lead to slow going before everyone on the table got moving. In the first battle in which I participated, my Bavarian division commanders’ chances were all down to the 40 percent level, and in the battle, due to some horrible dicing on my part, none of the commanders ever fully understood their orders. In this current battle, it took 2 full turns… 2 hours… before the Poles were on the move.

Alleviating the situation is the fact that if a commander fails to understand his orders on the first turn, he adds 10 percent, cumulative, to his chance of understanding on subsequent turns.

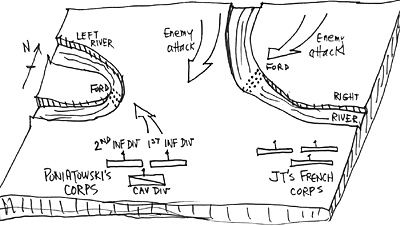

At the beginning of the battle, the French army commander sent Poniatowski an order which stated “… attack to river bank on left and then defend ford.” The map shows there are two rivers close by (I’ll call them the Left River and the Right River), each with a ford, and it looked like the Right River should be the one that I should be defending against, as enemy troops were descending on me from the right.

But orders is orders, I sez, and so I took the 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions and proceeded to wheel them to the left to advance to the Left River. Just to my right was my fellow commander, ol’ JT, commanding a French corps, and I assumed that the army commander had assigned JT the task of guarding my right flank.

And so I was rather surprised when JT took his troops, and instead of moving to his left to cover me, he sent them to his right on another mission. This put my left flank in the air… and sure enough, on the next turn (an hour later), down on the flank of my 1st Division came the enemy cavalry.

Later, I found out that our army commander had wanted me to move to the right to guard the ford at the Right River. But he confused his left and right, and so when he referenced the Left River, that was the WRONG river, since the Right River was truly the RIGHT River.

All this did little good for my 1st Division.

In the sequence of LGT, following the orders phase, comes the movement phase. That was when death and destruction came to the 1st Division. Movement is simultaneous, as it is assumed that units are locked into their orders and all orders will be written clearly and precisely. But this second phase gave rise to most of the problems that arose in the battle. Simultaneous movement has never appealed to me, and even less so here.

“Can my division hit his division before his division moves?” “Can he complete his wheel before contact?” “Can he change formation prior to contact?” Bob was continuously called in to adjudicate the situations as they arose.

Lottsa questions. Too many questions.

There is a provision for forming an “emergency square”, when hordes of cavalry descend on your infantry, but my unfortunate 1st Division couldn’t hack it.

The third phase in the sequence is the firing phase. My 1st Division couldn’t fire at all… the enemy was about to eat them up. Bob had prepared a table listing his thoughts on the probability-of-hit (POH) of infantry of the various nationalities. A couple of these listings, showing the POHs, are shown below. The given percentages are per-stand in the firing unit.

- French Line Inf 10%

Bavarian Line Inf 8%

British Line Inf 12%

Austrian Line Inf 10%

Polish Line Inf 8%

And after firing, comes the melee resolution phase. Lots of dicing here. First, the units in combat check their “elan” to see if they actually close. This is nothing more than a morale test. Elan values were rather low. I think my Polish troops had an elan value of 60 percent.

The oncoming cavalry passed their test, and, despite being hit in the flank, so did my 1st Division. The actual melee sequence is

- a Both units test elan

b Both strike

c Both test elan again

d Both strike

e Both test elan again

f Both strike

…and so on…

This goes on until one, or both, of the unit fails the elan test. The failing unit routs, and retreats back a full move… around 8 inches.

Just as in firing, each nationality has a POH of striking in melee. These numbers are fairly low… Bob’s theory is that units didn’t really strike each other in melee that often. The casualties appeared when they fled. And so, when the 1st Division failed its elan test, and routed, the cavalry got a free bite at the apple and knocked off 2 stands.

This occurred on Turn 3 of the battle, which began at 0800 and so Turn 3 took place at 1000. And then on Turn 4, 1100 hours, the Polish troops, still dutifully obeying their orders to move to the left, were hit again.

When Turn 5 began at 1200 hours, the status of my Polish corps was

- 1st Infantry Division Recovering from routing to disorder

2nd infantry division Routing

Cavalry division Routing

I think it was on Turn 5 that my army commander finally issued the Polish Corps revised orders. The new instructions said to guard my right flank! What else was new? In any event, the Poles were out of commission.

As for the procedures in LGT, I rather liked them… aside from the simultaneous movement problems, all seemed to flow smoothly.

Another source of delay in the battle, was the need to continuously reference the firing and melee charts to obtain the POH per-stand percentages of each type and nationality of unit in combat. Was it truly critical to give the Polish infantry an 8 percent-per-stand chance of hitting the enemy when firing, as opposed to a 10 percent-per-stand for the Austrians?

My druthers would have been to give all infantry the same POH in melee and in firing. Any pertinent nationality factors could have been placed in the ubiquitous elan tests… these were the true deciding factors in combat.

Movement rates were also a function of nationality... British and French elite infantry, in line formation, moved 6 inches per turn, regular British and French line moved 5 inches, while Spanish and Austrian troops moved 4 inches.

Again, to my mind, a wee bit more detail and grunge than I liked. But I’m a hard-to-please guy. In all, however, LGT gets a high grade.

Back to PW Review May 2002 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com