Rich Hasenaeur’s American Civil War rules FIRE AND FURY (FAF) supplanted Paul Koch’s ON TO RICHMOND (OTR) as one of the most popular ACW rules sets on the market. Why? I dunno... I was perfectly content with OTR, and because of the faults I found with FAF, it didn’t rise to the top of my favorites list. In fact, it lingers near the bottom.

I recently played in a game using Rich’s latest attempt to take his brigade-level game of FAF to a smaller-scaled game… to a regimental-size game, which I’ll term RFAF to distinguish it from the original FAF. I was informed we were using Version 7 of the effort, and from what I saw, we’d all better wait until Version 76 is offered.

The scenario was quite interesting… a number of Union regiments versus two Confederate regiments. Note that I say “a number of Union regiments”… I really wasn’t quite sure of what I was looking at. My two Union regiments started out with 9 stands each… I assume a stand represents a company, and the host said it represented around 40 to 50 men. And so my regiments each had, at an average of some 45 men-per-stand, 400 men in them.

What confused me was that you could take your 9-company, 9-stand, regiment and form it into two lines… the first of 5 stands, the second of 4 stands. Since two ranks of stands were permitted to fire, most participants did just that with their units… formed two ranks. Your unit received no decrease in fire power and you got a “plus” in the melee calculations. But once you formed up in two lines, it appeared that each line was treated as a separate unit… a “half-regiment”. I think the deal was that if both half-regiments were drawn up in a rather tight formation, the second rank touching the first, you’d get full regimental status. But if they became separated, you’ll be back to the half-regiment scheme of things.

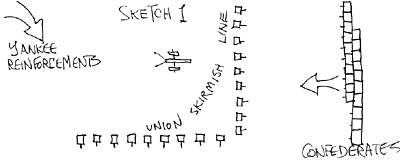

Sketch 1 shows the initial positions… initially, the only units on the field were my 2 Yankee regiments and my gun, and the 2 Confederate units. Both of my infantry units were graded as “green”, while the advancing Rebs were both “crack”… no contest here. But help was on the way… more Yankee units were soon due to arrive. Roxanne Patton was my Union partner… she was pushing the reserves as fast as she could.

Sketch 1 shows the initial positions… initially, the only units on the field were my 2 Yankee regiments and my gun, and the 2 Confederate units. Both of my infantry units were graded as “green”, while the advancing Rebs were both “crack”… no contest here. But help was on the way… more Yankee units were soon due to arrive. Roxanne Patton was my Union partner… she was pushing the reserves as fast as she could.

Another negative for my units, in addition to their greeness, were that they were both in skirmish order… the stands separated by around an inch. This reduced their fire power.

As in FAF, RFAF uses Fire Factors (FF) in the firing calculations. Stands contribute FF, guns contribute FF, and you add them up, take certain deductions (-1 if target under cover, -1 if firing unit is green, etc.), toss a 10-sided die, run to the fire table with your resultant FF, and see the effect on the target.

For many years, I’ve been ranting about the silliness of the FAF fire tables. The rules were published in 1990, and so I guess my ranting dates back some 12 years. Permit me to rant some more.

The normal way to create a fire table, that is to say, my way, is to draw up a chart listing the die roll versus the effect on the target. For example, look at the following, which took me all of 15 seconds to generate:

| MODIFIED DIE ROLL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,2 | 3,4 | 5,6 | 7,8 | 9,10 |

| No effect | Disorder | Disorder & lose 1 stand | Disorder & lose 2 stands | Disorder &lose 3 stands |

Note that the participant, whenever he sees a modified 7 on his die, will know that he’s disordered the enemy unit, and it has lost 2 stands. He tosses his die, applies the modifiers and looks up the result. A modified 7 will always, always, always produce the same result. Easily done, easily memorized, easily applied.

Now look at a section of FAF’s fire table:

| FAF’s Fire Table | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIRE FACTORS | No Effect | Disorder | Disorder & lose 1 stand | Disorder & lose 2 stands | Disorder & lose 3 stands |

| 8,9 | 1,2,3,4 | 5,6,7 | 8,9 | 10,11 | - |

| 10,11 | 1,2,3 | 4,5,6 | 7,8,9 | 10,11 | - |

| 12,13,14 | 1,2 | 3,4,5 | 6,7,8 | 9,10,11 | - |

| 15 to 19 | 1 or less | 2,3,4 | 5,6,7 | 8,9,10 | 11 |

| 20 to 24 | 0 or less | 1,2,3 | 4,5,6 | 7,8,9 | 10,11 |

Here, the Fire Factors are listed in the left column, and the modified die roll extends to the right. And the question becomes… what does a modified 7 represent? Sometimes, it’s disorder… and sometimes, it’s disorder and one stand lost… and sometimes, it’s disorder and 2 stands lost. It appears as if someone sat down and simply listed a random bunch of numbers.

The above is only a portion of the rather extensive FAF fire table. All of which means there’s no way of memorizing the table… you’ve got to have the sheet clutched to your bosom during the game… you can’t play without it. In the past, at various conventions, I asked Rich about his fire table and received an assortment of answers… he once replied: “Not me… someone else created the table…”. Another time: “Gosh! I never noticed that!” And so on.

Now I must note that RFAF carries on in the fine tradition of FAF, and has a similar table. In fact, an assortment of tables… if one is good, more is better. There’s a separate table for the result on each of the four types of units: crack, veteran, experienced and green. And a modified 7? Don’t ask! The same die roll, the same fire factors… don’t ask!

Basic Change in Firing

There’s been one basic change from the FAF firing procedure. Each infantry stand in FAF produced 1 Fire Factor. In RFAF, you don’t get 1 Fire Factor per stand… you get a Fire Factor determined by a grouping of stands. Here’s part of the table

- No of Stands Firing : Fire Factor

1 : -4

2 : -3

3 : -2

4,5 : -1

6,7,8 : 0

9,10,11 : +1

In a sense, this is okay… the table is a filter which encourages you to fire mass volleys with lots of stands. But to me, it’s a rather awkward way to determine the Fire Factors. The table isn’t linear… i.e., 8 factors are not twice as good as 4 factors, and all the table adds is the need to do yet another look-up in the firing procedure.

RFAF, Version 7, is an exceedingly low casualty game. When a unit loses a couple of stands, the Fire Factors that the regiment generates, according to the above table are either zero or negative, producing, for the most part, no effect on the target, or placing one disorder marker on it. To me, this was what made our particular scenario so interesting.

When the Union reinforcements arrived on the field, we Yanks outnumbered the Confederates over 2-to-1. I think we had around five full regiments on the field to their two. And yet the Rebs held on and fought back and just wouldn’t quit.

Given your ordinary, run-of-the-mill, fire-and-take-off-a-stand game, a 5-to-2 ratio of troops would result in the smaller side being quickly wiped out as stands would be removed twice as fast from the smaller side as from the larger. But in RFAF, the small loss rate permitted the Rebel force to take a disorder marker, recover the next bound, and fight on.

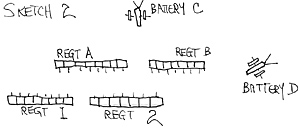

I should mention that the only time that a quantity of Fire Factors were generated was when several units massed their factors against one target. This, too, is a silly holdover from FAF. For example, consider two regiments, A and B, aligned against two enemy regiments, 1 and 2, as in Sketch 2. Regiment 2 can not only be targeted by A and B, but it’s also a proper target for Batteries C and D, each located a half-mile away from the infantry and from each other.

I should mention that the only time that a quantity of Fire Factors were generated was when several units massed their factors against one target. This, too, is a silly holdover from FAF. For example, consider two regiments, A and B, aligned against two enemy regiments, 1 and 2, as in Sketch 2. Regiment 2 can not only be targeted by A and B, but it’s also a proper target for Batteries C and D, each located a half-mile away from the infantry and from each other.

The Colonel of Regiment B says to his radioman: “Humphry, get on your multi-frequency, over-the-horizon radio, and tell Regiment A to ignore the unit to its front and fire on enemy unit 2, and also contact the commanders of Batteries C and D and tell them to support my fire on unit 2. That way, we’ll be able to add all our Fire Factors and blast unit 2 away.”

This inter-unit fire coordination was permitted in FAF, but there it was worse because of the scale involved. Batteries a mile away from an infantry unit could magically add their Fire Factors to the infantry factors, and once again, RFAF carries on the fine tradition.

I mentioned that when the full Yankee force arrived, we outnumbered the Rebs 2-to-1. And yet they hung on and eventually won the battle on sheer guts. It wasn’t that they “outshot” us… the casualty rate is so low… but at the post-game, post-mortem, the ump stated that around half of the Union casualties, i.e., half the stands lost, occurred due to lousy test results when we tossed on our Maneuver Table.

When the active side moves its troops, it tosses a die for each regiment, looks on the Maneuver Table and sees if the unit can move, or hold or whatever. When dicing on this table, both Roxanne and I continually tossed a series of “1’s” on the die… and a toss of “1” is bad news. Your unit loses a stand, and runs back a full move.

The sequence for the bound for RFAF is the same as that used for FAF. First, one side is active, and then the other side is active. Here’s the sequence of the full bound.

| First Half | Second Half |

|---|---|

| (a) Side A moves | (e) Side B moves |

| (b) Side B fires | (f) Side A fires |

| (c) Side A fires | (g) Side B fires |

| (d) Resolve melee | (h) Resolve melee |

Note that, during the entire bound, both sides get the same fire power… they get to fire twice. In a prior article on the rules COLUMN, LINE & SQUARE, I mentioned that this type of sequence is inappropriate for the horse-and-musket era.

Loading and preparing a musket takes an appreciable amount of time. And if one side is sitting in a defensive position, it can devote all of its time to prepping its muskets for firing (load powder, tamp, load ball, tamp, prime, aim, fire). In contrast, if a side is continually advancing, it should have very little time to load and fire its weapons. Which means that a side that doesn’t move should be given proportionately more fire power than a side that moves up.

Another carryover from FAF was the dreaded “pass through” fire. On the first run of the game, one of my green units was given orders to fall back… the oncoming crack Confederates were just too powerful. And so I tossed on the Maneuver Table, and Glory Be!… the regiment actually obeyed my orders. This would be Phase (a) on the above sequence chart. My regiment falls back around 12 inches.

Now Phase (b) comes and the Rebels fire. And they target my unit, which just fell back as fast as their little feet could carry them. “Ouch!”, sez I to the umpire. “My boys just fell back, they’re out of range, they’re out of breath, they’re in the woods, they’re not visible! What’s going on?”

Aha!, replied the umpire… the Confederates are not firing at your unit where it IS… they’re firing at it where it WAS prior to your move!

I was first introduced to the FAF pass-through fire provisions some years ago. The comments of all at table-side were that it was a silly rule… but it was a rule nontheless… being printed in the published manual, it had been given an aura of legitimacy, and had to be obeyed. And so, once again, RFAF carries on with the traditions of FAF.

Another interesting instance of RFAF procedures occurred when a Confederate regiment contacted one of my own. In Sketch 3, I’ve shown the configuration after movement in Phase (a), and just prior to the firing phase. Note that contact has been made solely via the end stands of each unit.

Another interesting instance of RFAF procedures occurred when a Confederate regiment contacted one of my own. In Sketch 3, I’ve shown the configuration after movement in Phase (a), and just prior to the firing phase. Note that contact has been made solely via the end stands of each unit.

The major portion of each of the concerned units extends way, way out beyond the actual line of contact. By definition, all stands of both units are “involved”, and will be considered in the melee calculations, even though, from the visual presentation on the table, most of the stands are simply out of it.

In the fire phase, Phase (b), I asked which of my stands were permitted to fire defensively, and was told to measure stand by stand, and only those stands which had an enemy stand within their arc of fire could volley. Which essentially meant that only two of my stands could fire… the others were useless. My thought was that if, by definition, all of the stands were going to be caught up in the melee, why couldn’t they add their fire power in defense?

I wasn’t sure of the game scale for RFAF. In FAF, rifled musket range extends to 8 inches. Assuming that the 8-inch range represents the 300 yard range of the weapon, then FAF’s scale is around 40 yards per inch. In RFAF, rifled musket range extends to 18 inches, and thus the scale would appear to be around 16 yards per inch.

I noted another carryover of FAF to RFAF. This concerned the melee chart and the outcome of the combat. In melee, as in firing, you add your points to the toss of a die, and the sides compare totals. The side with the higher total wins, holds the position, and loser falls back, disordered. If the delta in the totals is great enough, the loser will also lose a stand.

But regardless of what happens to the loser, the winner of the combat loses nothing! A unit that wins a melee will stand there, just as fresh as when it started out. It could engage in ten melees in a row, win all of them, and show no signs of exhaustion, of shortness of breath, of disorder, etc.

This is similar to the DBA/DBM scheme of things. In these rules, a stand is either dead, or its in great shape… nothing in between, regardless of the number of battles in which it has been engaged.

Now here’s what’s absolutely fascinating to me. FAF is probably the most popular ACW set of rules on the market on both sides of the Atlantic. Rich Hasenaeur has sold his rules to the wargaming world, and while he didn’t become as wealthy as Bill Gates from the sales, they permitted him to purchase a condo in Majorca, several Rolls Royces, and a 150-foot yacht with a jacuzzi on the deck. Isn’t it unfair for a guy to have a jacuzzi on his 150-foot yacht, when he refuses to acknowledge his own fire tables? I think he should, at the least, turn in his jacuzzi.

There is no doubt in my mind that, despite the problems I outlined above with RFAF… and I should note that these are problems in my own mind, and didn’t appear to trouble the other participants in the battle… the popularity of RFAF, Version 76, will soon overtake that of FAF, and Rich will be able to afford a small villa on the Riviera.

Back to PW Review January 2002 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com