For years I’ve scoffed at 6-sided dice and 6-sided-dice-users. If you’ve got percentage dice, with the ability to track everything in 1 percent increments, use ‘em!

For years I’ve scoffed at 6-sided dice and 6-sided-dice-users. If you’ve got percentage dice, with the ability to track everything in 1 percent increments, use ‘em!

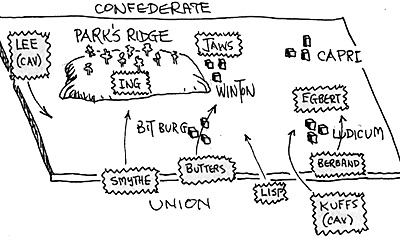

But old age is coming upon me, and I decided to return to the 6-sided cubelets, just for old times sake. The scenario I chose was the Battle of Park’s Ridge, sketched in the accompanying map. Here, 5 Union brigades advanced upon the Confederate position on the ridge, the 4 defending Rebel units were whupped, and this is how it happened.

In truth, I somewhat exaggerate… I fought the battle twice, and the first time, the attacking Yankee troops were driven off, mainly because I didn’t give them enough units. In that first tryout, I had equal numbers of Yankees and Confederates, and the Rebs handled themselves well… the Union force couldn’t hack it.

But the first go-round gave me some new ideas for the system, and with these, plus one additional brigade for the Yanks, all seemed to go well on the second effort.

This was a tactical battle… one of my 15mm stands (approximately I-inch-by-1-inch) represented a company, and I clumped 5 companies together to form a regiment, and further clumped 3 regiments together to form a brigade. Each brigade was equipped with a battery and a commanding brigade officer, and it was the brigadier whose fortunes were tracked.

The Union had 5 brigades, and at 3 regiments per brigade, a total of 15 regiments. I didn’t want to keep data for every regiment on the field, and so I recorded the “Efficiency Levels” (EL) of the brigadiers. My thought was that when a brigadier saw that his men were getting walluped and smashed and battered, he’d have second thoughts about continuing the fight, and, at some point, he’d pull his men back.

This approach meant that I’d have to quantify the brigadier’s outlook. Each brigadier was diced for… their ELs started at either 100 or 90 or 80. When any of his units took casualties, the brigadier himself would be affected, and his EL would go down. If the EL ever reached zero, then all the fight was taken out of the general, and he’d pull back and fight no more.

On the way down to zero, there were certain key EL levels… for example, when a 100 EL general reached 65, one stand would be removed and his men would engage in combat less effectively. Another way-point occurred when he reached the 40 level, when another stand would be removed. These mandated removals were in addition to his normal losses in battle due to fire and melee, and the combination of the two guided the brigadier’s fortune.

Now for the 6-sided dice trick. The 5-stand regiments were the maneuver and combat elements, and both in the firing and melee phases, each company (stand) in the regiment tossed a 6-sided die. And when the dice were tossed, you’d look for doubles:

- Double 1 (i.e., 1, 1) Target brigadier takes 5 EL loss, places one stand of the target regiment in the off-board Rally Zone (to be recovered during an administrative phase) and the target regiment takes a morale test.

Any other double Target brigadier loses 3 ELs

Normally, 5 dice were thrown. But a battery tossed an extra die for canister, and cavalry, when engaging in melee, got 2 additional dice, and if a targeted regiment was in cover, the tossing unit would throw one less die.

What was most interesting to me was the fact that when I grabbed a handful of dice (if 5 dice could be called a ‘handful’), there was a very pleasant ‘squnchy’ feeling to the affair… somewhat like squnching a bag of marbles. Perhaps, I thought, these 6-sided-dice advocates had something going for them. But back to the battle.

Brigadier General Butters led the Union attack. His brigade quickly occupied Bitburg (there were no rebel forces defending the town) and commenced an advance northward toward Winton. Confederate Brigadier General Jaws and his men sat in Winton, and they wanted no part of Butters.

To the left of Butters was Brigadier Smythe, and Smythe had the difficult task of trudging up Park’s Ridge and tossing Confederate General Ing’s brigade off the heights. Both Smythe and Butters got clobbered, and from two different sources.

On the western side of the field, Smythe was attacked by Lee’s Confederate cavalry, and although he managed to fight off two attacks, he saw a large chunk of his EL points get bitten off.

At the same time, Butters suffered from a continuing series of canister blasts. He faced Brigadier Jaws’ cannon in Winton, and in addition, General Ing had set 2 artillery pieces on Park’s Ridge directly in front of Butters’ line of march. Thus every firing phase, Ing got to toss two sets of 6 canister dice (one set of 6 for each battery), looking for doubles, while Jaws tossed one set.

The result was that Ing and Jaws tossed lots of double-1’s, and double-1’s meant double trouble for Butters. First, his targeted regiment immediately lost one stand to the Rally Zone, and second, Butters’ unit took lots of morale tests. The entire Butters brigade fell back into Bitburg.

A morale test had the affected regiment toss one 6-sider with the following result:

- Toss of 1, 2 Regiment holds position, returns fire

Toss of 3, 4, 5 Regiment holds position

Toss of 6 Regiment falls back in column 10 inches, one stand placed in Rally Zone, brigade loses 5 ELs

Unfortunately for Brigadier Butters, too many 6’s showed up… his troops obviously felt safer in Bitburg. But even though Butters’ brigade had to fall back, Brigadier Lisp saved the day. He. too, headed for Winton and took some of the heat off Butters.

And who took the heat off Lisp? ‘Twas the Union cavalry, commanded by Brigadier Kuffs. His horsemen kept General Egbert’s brigade busy. Egbert had initially taken position way out in Capri, and he advanced toward Ludicum, thinking he’d attack Lisp’s flank, when Kuffs’ boys plowed into him.

In the sequence, after regular movement and contact, and cavalry movement and contact (these are two separate phases), there’s an opportunity for target units to react and fire defensively using Reaction Points (RP). Each side was given around 4 RP each half-turn to react in this manner. The target was first assigned one RP, and then a 6-sided toss of 1-to-5 indicated the order was received and understood, and the unit commenced firing.

I noted that the Confederates misunderstood, or never received, their orders much more frequently than the Union units. This didn’t help the Rebel cause any, since (a) there weren’t that many RP around to throw away, and (b) the Rebs were outnumbered to start with.

If Kuffs’ cavalry stood up to the Confederate defensive fire, melee began. Each stand tossed a die, and another die was thrown if a friendly regiment was nearby to spur the unit on, and another die if the regiment was on high ground, and another 2 dice if the attacking force was cavalry, and so on. The result was that each unit in melee tossed around 5 or 6 dice.

Just as in the firing procedures, tosses of double-1’s knocked 5 points off the opposing brigadier’s EL, while other doubles knocked off 3 points. After all dice were thrown and all EL losses were recorded, I looked at the ten’s digit of the ELs of the two commanders (as an example, if Kuffs’ EL was 54, his ten’s digit was 5). And then I multiplied the ten’s digit by a die, and the winner was the higher product.

The losing regiment retreated, and its unhappy brigadier lost yet another 5 EL. In this manner, Kuffs’ cavalry drove Egbert back in fine style, keeping him from interfering with the Union attack on Winton. Smythe pulverized Ing, who was defending Park’s Ridge, and reduced Ing’s EL to zero. The entire right flank of the Confederate force vanished, and the Union triumphed.

Conclusions. Are there any conclusions? Should there be any from my jaunt into 6-sided-dice land? The battle took 2 hours, I enjoyed myself, but I think I’ll stick to percentage dice.

Back to PW Review October 2001 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com