We three, Bob Wiltrout, Fred Haub, and Wally Simon, devoted wargamers all, traveled some 5 hours to Raleigh, North Carolina, to play a game of IN THE GRAND MANNER (ITGM), a set of rules for the Napoleonic period developed by Peter Guilder. Guilder passed away some years ago, but his rules, for no apparent reason (to me), live on. In particular, they are played at the Wargames Holiday Centre in Folkton, England.

Our host for our Raleigh trip was Buddy Hoch, and both he and Bob Wiltrout are avid ITGM devotees. About a year ago, they spent several days at the Centre, basking in the delights of ITGM, and had a delightful time. They said there were 8 players per side, lots of umpires, lots of table space, lots of troops, and the weekend cost at the Centre was £125, or $190… which includes a couple of lunchtime meals. Add to this the costs of room, other meals, plus airfare, and, in truth, it doesn’t sound like too bad a holiday.

Buddy Hoch’s Raleigh set-up is, in a word used by the Valley Girls, awesome! His game room is away from his main house, and the gaming area measures 24 feet by 32 feet… a large, single, well lit, unbroken area with no pillars or posts to interfere with the gaming layout. Buddy has two parallel tables, side by side, each 6 feet in depth by 24 feet long, enabling a battle to be set up encompassing a total of 12 feet in depth, so that troops can be moved from one table to the other across the between-the-table space of about 3 feet.

The Wiltrout/Hoch troop inventory focuses on 30mm Napoleonic figures… Surens, Staddens, etc. Bob has his own huge collection, while Buddy has an even larger collection of well over 10,000 figures, all nationalities, all beautifully painted, all based solely for play with ITGM. Their intent is to be able to set out any encounter, any battle, of the Napoleonic era.

ITGM, in terms of its figure set-up, is a clone of COLUMN, LINE AND SQUARE (CLS), the old Fred Vietmieir rules. The basic mounting element is termed the one-stand company, and several companies are combined into battalions, which, in turn, are organized into regiments, which are then organized into brigades.

My Command

I was a Prussian commander, and the basic fighting and maneuver element of my force was the 4-company-stand battalion. Each of my Prussian company-stands had 8 figures on it, giving a total of 32 men per battalion.

My regiments were each composed of 3 battalions… since each battalion was made up of 4 company-stands, my regiments had 12 stands each. Three regiments comprised an infantry brigade (36 stands). And the regiments also come with a couple of skirmish stands to be broken off from the main units.

My command also included a cavalry regiment… 3 squadrons of 6 stands each… plus three batteries.

Each battery was composed of 4 stands… 3 guns plus a howitzer. To deploy the battery, all 4 guns side by side, you needed an 8-inch wide space, which tied up quite a bit of frontage. All the stands were fairly large… my infantry stands measured, I think, 3-inches across to accommodate the figures on them… 8 figures in two ranks of 4 men each.

ITGM mandates that each nationality has its own unit basing.

As I mentioned, my Prussian stands had 8 men on them, with 4 stands per battalion (32 men). The French stands had 6 men on them. Six French stands made up a battalion of 36 men. And the Austrian battalions in our battle had 48 men in them.

In short, in the 30mm scale, ITGM requires a lot of table space, of which we had more than enough.

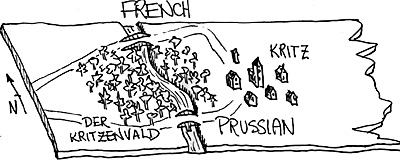

On the map, I’ve sketched my 8-foot portion of the entire 24-foot field of battle, the western section. Fred Haub, commanding the Austrians, was way, way over toward the east, on the right at the edge of the world… he faced Buddy Hoch’s Frenchmen, and, in effect, due to the large table size and distance between the forces, this encounter proceeded independently of the rest of the battle.

My Prussians came on from the south. I was permitted to place 2 battalions (8 stands) in the town of Kritz, and I also immediately had my troops and skirmishers make for the woods, the Kritzenvald, which proved a mistake. It turned out the Kritzenvald provided no cover, and all it did was to reduce the movement of my troops (skirmishers move 7 inches, infantry-in-line, in the open, move 5 inches).

Skirmishers come in groups of 6 men. When they fire, toss a 6-sided die for each man, and at short range (within 4 inches), a 4, 5 or a 6 kills a target figure. At long range, (up to 16 inches), only a 6 kills.

Regular volley fire is calculated in a completely different manner. When my 4-stand battalion was in line, all 32 of my men could fire. This figure was then referred to the Fire Chart, a huge one-page chart of numbers… men firing listed along the left edge, and along the top, a modified random dice toss.

Toss two 6-sided dice, get the sum and modify with whatever is appropriate… a +4 for first fire, a -4 if firing unit moved, a +2 for rested weapons, a -4 if target in hard cover, a +2 for British Guards… there were 11 potential modifiers. Then reference the number of men firing with the modified dice roll, and pick off the number of casualties.

Our hosts voiced complaints with the Fire Chart. It seemed that it favored large volleys. For example, the total casualties inflicted when firing two 12-man volleys, were less than those inflicted by a single 24-man volley. Why the complaints? These guys had been playing the ITGM rules for years… if you don’t like ‘em… change ‘em!

The chart problem manifested itself with the different unit sizes. My Prussian battalions were the smallest, of 32 men, hence they had the smallest effect. The French battalions of 36 men had a slightly greater effect, and the Austrian battalions of 48 men, had the greatest impact.

Thus far, we have skirmisher fire, and volley fire, and now for artillery fire, we have yet again an entirely different method of calculation.

First, look at the target frontage. There are 3 classes… Class A consists of lots of massed troops (12 or more men wide), Class B is somewhat less, and Class C is a target frontage of only 3 or 4 men. The class determines the pips needed on a 10-sided die roll to strike. For example, a toss of 1-to-3 will strike a Class C target (a rotten target) at long range, while a toss of 1-to-9 will produce an impact on a Class A target at short range.

A battery consists of 4 stands, 4 guns. Toss a 10-sided die for each gun and see if an impact occurs according to the target classification.

But we’re not through yet! Each of the successful hits we obtained from our first series of four 10-sided dice throws gave us a number of Fire Points. Now we total our Fire Points and refer to the artillery Fire Chart, similar to the volley Fire Chart, but different!

Now we toss two 6-sided dice, get the total and go into the chart. Cross reference the Fire Points we have (which are listed along the left edge) with the 6-sided dice total (listed along the top) and pick off the casualties.

Questions

Which brings up a couple of questions. Why are we suddenly tossing 10-sided dice? (I must note that Bob Wiltrout is ecstatic about this historically accurate simulation of determining which of the guns in our battery hits). And why do we use a Fire Chart for artillery completely different from that used in regular volley fire? It turns out that the regular Fire Chart is also used for computing melee casualties… if one chart is versatile enough for both volley fire and for melee, surely it’s good enough for artillery? Surely?

But who am I to find fault with ITGM? There is no doubt that the authors undertook a massive historical study to best display the effects of artillery fire, and I can only bow my head in awe.

ITGM uses a sequence in which one side starts moving its troops from the right, while the other side starts moving from the left. In the middle, you sort of ‘talk it out’. This is an almost- simultaneous sequence, and leads to certain surprises. For example, in Bound 4, I moved my skirmishers within musket range of Bob’s French horse-gun battery. I started from the left, while Bob was busy working from the right.

When Bob reached the left side of the field, and saw my skirmishers in position and ready to fire, he immediately limbered his horse-battery and ran the unit back, taking them out of range, leaving my skirmishers with no targets.

Not too bad, since the sides alternate moving from left to right each turn, and each, therefore, gets a chance to react to enemy movement on different halves of the field. The original Peter Guilder text for ITGM was a mess. It was not clear, not organized and the tables and charts seemed to be located randomly.

Bob took it upon himself to reorganize the rules booklet. He completely revamped it, with each chapter referring to a particular phase in the sequence, containing all the charts and instructions necessary to carry out the functions of the phase. Thus, for example, for the volley fire phase, the procedures and modifiers and charts for determination of casualties are detailed, and are then followed by the procedures for the morale tests which the target units must undergo. There’s no need to flip through the book from chapter to chapter, looking for information… each chapter is complete in and of itself.

Sometime during the battle, I took one of the defending battalions out of Kritz, advancing to the north, leaving one battalion in the town. Bad idea… Bob’s French units quickly converged on my single advanced battalion… during the movement phase, he was able to get two of his battalions to contact my own.

My unit fired defensively, and one of the French battalions took a morale test, but easily hung on. Then it was the melee phase, and we went into Round 1 of the melee procedures. Here, the stands in contact fight it out, counting up figures, applying modifiers, and then referring to the Fire Chart I mentioned before, the one used for the volley fire procedures.

The side with the most casualties then takes a morale test. If the side holds, Round 2 begins, and for this round, everyone joins in and additional battalions can advance and join in to reinforce the first. Again, all the figures are counted, and the Fire Chart consulted. For this Round 2, we had my 30 or so Prussians facing 2 whole French battalions, a total of over 60 men. I already mentioned that the chart is on the side of the big battalions… one strike of 60 will more than double a single strike of 30… and my Prussian losses mounted up. Another morale test for the side that took the most losses… me!… and this time my unit broke.

If my unit had held, we would have engaged in the third and final round of melee.

A couple of bounds later, the French attacked Kritz itself… another 2-on-1 assault. And the town fell to the French.

Just to the east of Kritz, the French mounted yet another 2-on-1 attack. Evidently, that seems to be the way the rules should be played… take advantage of the imbalance in the chart. But this time, despite their severe losses, my battalion held on for three complete rounds. In this case, all units withdraw from combat, and require one turn to form up.

I soon had all of my three brigades on the Prussian left flank falling back… either routing or in disorder.

Way over to the west of the Kritzenvald, I had one of my units of light cavalry charge a battalion of Frenchmen. There’s a test to see if a cavalry unit charges home on infantry. And for my light unit, the test was to toss three 6-sided dice and toss a total of 19 or so! Face it!… this is hard to do with three 6-siders! ITGM simply doesn’t want light cavalry to charge into infantry, whether they’re in square or not. When I asked about the charging provision, it was explained that the function of light cavalry was not to charge into formed infantry units, and the rules purposely made it so. If the infantry were unformed, the cavalry would get a +4 modifier on their dice toss, thus requiring a total of 15… still pretty hard to do. Heavy cavalry, cuirassiers, require a basic toss of 8 or more on their 3-dice toss to close.

At first, I began to read and follow the charts and modifiers for each of the phases within the sequence.

- There’s first, a phase in which units that routed during the last turn, run back.

Second, a charge phase, wherein charging units are advanced towards their targets.

Third, a fire phase of three parts

- Skirmishers fire first

Artillery fires second

Volley fire is third

Fourth, resolve melee

Fifth, attempt to rally retreating and routing units.

Every one of these phases requires multiple references to morale tests. When taking a morale test, a unit tosses three 6-siders, looking for a high total. You first go to one chart in which the particular total you need depends upon the initial figure strength of the unit. Then you go to another chart, where there are over 20 modifiers for the actual morale toss, and around the second turn, I gave up on reading the charts, and let Bob Wiltrout do it.

Modifiers for “general within 12 inches… +1”, and then “a friendly unit retreating within 12 inches… -1”, and “enemy unit within 12 inches… -1, and “outnumbered 2-to-1 in melee… -2”, and “being charged by troops of equal status… -2”, and “unit in hard cover… +2”, and “advancing in column of attack this turn… +1”, and “friendly unit routing… -2”, and so on… over 20 of ‘em.

This list is a simple copy of the old WRG morale listings, which were used by Phil Barker up to the WRG 6th Edition. Finally, in WRG 7th, even Phil Barker gave up on it, and reverted to a quick and dirty, simple 6-sided morale die roll. But, in ITGM, the list lives on.

As I said, each of the phases and sub-phases within the sequence requires units to take a morale test. Morale tests for units charging and for closing and for holding against a charge and for taking casualties and for each round of melee. This was the one item that significantly held up the game, as both sides (except for me, of course), during each phase, went down the modifier listings.

Heard That Before

Bob stated that if a person played the rules regularly, he’d become sufficiently familiar with the modifiers so as to preclude reference to the charts. I’ve heard that before. And Bob also indicated that at the Wargame Holiday Centre, the umpire would say: “Toss the dice and we’ll see if it’s close, and if so, we’ll get into the nitty-gritty of the numbers”.

To my mind, not the way to go. Over a decade ago, Fred Haub and I ginned up our own morale tests for our Napoleonic system… for every good thing you could think of, you got a +1, for every bad thing your opponent could think of, you got a -1. All the modifiers were of equal value. Looking at the partial list I gave above, how does a unit know it’s being charged by a unit of equal status… -2, and how does it know if a friendly unit is retreating (-1) or routing (-2)?

We played our ITGM battle on Friday afternoon and for most of Saturday… around 10 or 11 hours total. I’m not a fan of long, drawn-out battles. My interest factor and attention span go completely to pot if a game lasts longer than 3 hours.

Despite all the problems I pointed out (problems to me, and not necessarily to anyone else), ITGM provided a good game. I went home happy.

Back to PW Review October 2001 Table of Contents

Back to PW Review List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 Wally Simon

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com